The word ‘Nakba’ literally means ‘disaster’. And for hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, and millions of their descendants, it was exactly that.

In 1948 Israel was just a fledgling nation. It had been granted independence, and classed a ‘Jewish State’. But the majority of Israel’s inhabitants were non-Jewish. They had lived peacefully, side by side with small Jewish communities, for many centuries. But they posed a problem for the new Zionist chiefs, who wanted to create a Jewish majority in their new land.

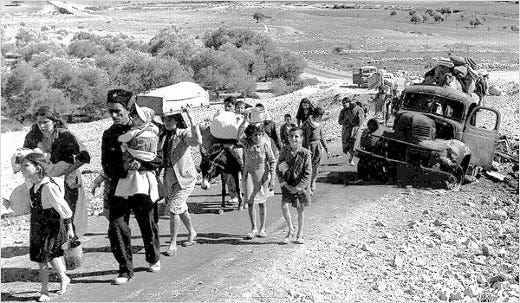

So groups of Zionist militias formed across the country. Using weapons left behind by the British army, they began to clear Palestinian villages. On dozens of occasions they massacred the inhabitants. One hundred innocent civilians were killed in the village of Deir Yassin alone. In other villages they forced the locals to flee. Whole villages escaped before the Zionists reached them — petrified that they would be the victims of another massacre.

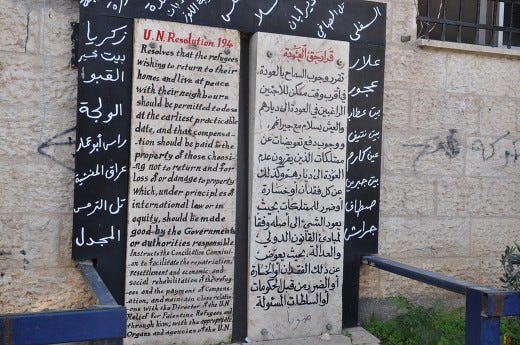

Over 700,000 Palestinians fled for their lives. When the war was over, they tried to return, as is their right under UN Resolution 194, section 11. That piece of international law states: “Refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.”

However, the new Israeli government had instigated their own laws to stop Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes. Over four million acres of their land were given to new Jewish immigrants. The indigenous population were forced to live abroard in refugee camps.

Today, over seven million Palestinians live in refugee camps, mainly in the West Bank, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. Many of those experienced the Nakba first hand. Many more descend from the victims of the Nakba. Pretty much all of them dream of returning home.

In February 2015 I visited some of those refugees in the West Bank and Jordan. Their stories inspired large parts of my novel, ‘Occupied’, the first chapter of which is based on the Nakba itself.

Here’s what I learned…

DHEISHEH

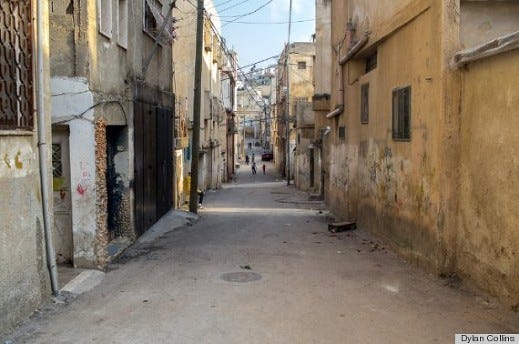

Dheisheh, on the face of it, looks like any other suburban district on the outskirts of Bethlehem. Some children wave and say ‘hello’. Some children work; washing their drives or taking the rubbish out. They seem like they’d rather be playing with the other boys and girls.

Tightly packed white houses shadow the streets which snake up and down the hillside. Black bars protect their windows. Colourful plants sit on their windows sills. Children sit on ledges, swinging their legs back and forth.

Yet every now and again, something catches the eye to remind you that this is no normal suburb. As you enter you see an old turnstile — the remnant of a time when this camp was surrounded by an 8 metre tall fence, and subject to a curfew. An office block is surrounded by a line of UN cars, which are often seen on the camp’s narrow roads. Some graffiti lists the 49 villages from which the refugees fled, alongside an excerpt from UN Resolution 194. Other graffiti shows two Palestinian fists smashing through Israel’s apartheid wall.

“This is our bus station,” a tall social worker tells me with youthful passion and angst. “We’re not here to stay. We’re just waiting here until we can go home.”

Life is not easy.

“Once the Israeli soldiers tried to grab my phone,” the social worker continues. “I pulled it back and told them they’d have to take it by force.

“They ask intrusive questions all the time, like ‘Are you a Christian or a Muslim?’

“I haven’t been able to go to Jerusalem for seven years.”

But the social worker doesn’t blame the soldiers themselves.

“I saw a soldier holding a gun once,” he laughs. “And the gun was bigger than the soldier! They’re just kids.”

Instead, the social worker blames the politicians.

“Two Rabbis came to Palestine in the 1890s,” he explains. “They went home and told their people, ‘The bride is beautiful, but she is married to another man’. They knew that this land was ours. That we were here first.

“These days the Israelis have forgotten that. They tell everyone that they came to this land and no-one was here. They’re trying to re-write history to suit their own agenda.”

We walk through the camp, which is only half a square kilometre in size. Ten thousand people live here, over 70% of whom are children.

The social worker tells me how it grew:

“At first, people lived in tents, which were cold and fell down whenever it rained. In 1952/53, those tents were replaced with 3m by 3m concrete rooms. Whole families lived, cooked and ate in those small places. Then, in the 1980s, those rooms were knocked down and proper houses were built.

“But they’re not good. In the summer it’s too hot, and in the winter it’s too cold.”

We walk past a row of these houses, and a 3m by 3m unit which remains from the 1950s. Every building, regardless of its size, has a row of water tanks on their roof.

“The Israeli settlers (who represent 20% of the population) control 80% of the water. It’s only pumped through the camp once every 15 days, so people have to hoard whatever they can.

“Oslo said the Palestinians can have what they can hold, but the air and the earth belongs to the Israelis.”

JALAZONE

I met a group of British activists at the ‘Women In Hebron’ collective who said I should visit the village of Jiffna.

Jiffna is as beautiful as those activists had suggested. Fields jut in and out of the mountainside, forming steppes which house a splattering of olive trees. Occasionally a house pops up here or there. Horses chew the grass. Goats graze in the valley below.

But people are in short supply here.

When I tell the first man I see that I’m here to talk to Palestinians, he suggests I head for the opposite side of the valley, to the Jalazone refugee camp. A few minutes later I’m being given a lift, for free, to that camp.

Fatah flags adorn the monument which sits in a tiny square at the centre of this camp, alongside pictures of two political martyrs; a Fatah leader who was shot dead in 2002, and his son; a mere slip of a boy who was killed in 2009.

On one side of this square is a butcher’s shop, where a Fatah plaque sits on the worktop. The butcher sits opposite me, smoking. He sends a teenage boy away, who returns with some coffee. We take a sip each, then the butcher tells me his story.

“My father was a butcher,” he says in broken English. “He taught me how to butcher. Everything I know, I learnt from him.”

The butcher nods towards a picture of his father, then a young boy comes in and places an order. The butcher cuts a strip of meat off a carcass which hangs in his fridge, dices it, mixes in some chopped onion and herbs, then passes it back to the boy.

“I have to work as a history and politics teacher, down in the valley,” the butcher continues. “I’d rather work as a butcher full time, but there’s just not enough work.”

Unemployment is high in this camp, and many people have to rely on UNWRA rations to survive. But even that is being cut back, because UNWRA’s limited resources are being diverted to deal with the Syrian refugee crisis.

I leave the butcher’s and walk past a wonky digger which has a flat tire. Two legs lift it up above the trench it has been digging. I walk past more pictures of the two political martyrs. I walk past a clinic and playground.

“They’re the only ones here,” an articulate student tells me. “Seventeen thousand people live in Jalazone, and we only have one clinic. No police! No hospital!”

The student continues to talk as we make our way to his grandmother’s house.

“Once, I was arrested at 3am in the morning,” he says. “The army came into my home, looked at my brother, then picked me out at random. I was accused of being a member of Fatah, which is not illegal, and put in prison for two years.

“They never charged me with any crime. There wasn’t any trial.”

The students sighs.

“It’s not unusual; settlers throw stones at us when we play football. Their settlement is above our school. No-one stops them.

“But it could be worse. I knew someone who was shot by a sniper whilst he sat on his roof.”

We walk on in silence until we reach the student’s grandmother’s home.

NAKBA’S DAUGHTER

“Life in Beit Nebela (‘House of God’) was amazing,” the grandmother tells us. She pinches her fingers together, kisses her fingertips, then flicks them open.

“We had land, fruit and vegetables. We didn’t need anyone or anything else.

“We had sheep and cattle, but our village specialized in oranges and olives. Every village had its own speciality.

“People came from Egypt and Jordan to see our village. My dad would get two of them to help with the harvest. My mum stayed inside.

“I was only ten years old at the time of the Nakba.”

We’re sitting on the comfortable sofas which surround a low table inside this spacious living-room. The student translates for his grandmother, who has supplied us all with ample amounts of sweet tea. The student’s friends all listen in intently.

“The next town along from ours, Abessour, made a three month truce when Israel was first established. Only five percent of the population were ‘Israelis’ back then; they needed time to get weapons and become strong. The English encouraged that village along, saying, ‘Get out for three or four days, then everything will be fine’. So everyone from Abessour came to Beit Nebela.

“But they weren’t ever able to return.

“After three months, the Israelis became strong. They started picking off the smaller towns.

“They came to our village, protected by British soldiers, who stood on either side of them. They looked like cowards, stood there in the middle.

“We were helpless; the Israelis had tanks, and whilst some of the villagers bought guns, they didn’t have any bullets. So my parents took us up into the mountains to hide. We only expected to be there for a day or two, so we didn’t take any possessions. No clothes. No food or livestock.

“We moved onto a town called Dair (‘Mystery’), and then onto another town, and then onto another town. We always hoped we could make it back. But every town we went to, the Israelis killed people. We heard about the Deir Yassin massacre. The people we met in the hills told us about other killings. The sentries we left back in our village were never seen again.

“The Israelis took over more towns, and pushed us further and further away. Then we heard of a Swedish head of security who wanted to speak out. He was assassinated.

“That was the last straw for us. We decided to head for the West Bank.

“Some people from our village died from cold and disease on the way. We struggled to find water. We didn’t have any possessions; we left them behind because we thought we’d be going back.

“We spent four years in one town, ten in the next. We made it to Jalazone after seventeen years.”

But even now, sixty seven years later, with her family scattered across Palestine, Jordan and the USA, this grandmother still dreams of returning to her ancestral village.

“Hope is in the hands of God,” she says. “Governments rule, but God is the only ruler.

“The Israelis frighten me when they come. They throw gas into our homes, just to scare us. In 1991 they beat my head and ankle with a rock.

“They see that we can’t be beaten, but it’s not a fair fight.

“Still, one day, I believe we’ll return home.”

CONCLUSION

As a Jew, I was made painfully aware of the horrors of ethnic-cleansing whilst I was just a small child. I learnt about the holocaust, in which six million Jews were killed by the Nazis, whilst I was at school, religious school, synagogue and home.

So the fact that some Jews, the Zionists, would start their very own process of ethnic-cleansing just three years after the holocaust, is an irony that is not lost on me. It is, however, lost on most Zionists.

The Zionists are continuing their ethnic-cleansing today. In Hebron, they are evicting Palestinians from their town centre homes, as detailed in my first blog in this series: ‘Hebron — Politics and Protest’. A similar process is taking place in East Jerusalem; the proposed site for the capital of a new Palestine.

Rather than try and learn from the mistakes of the past, the same horrors are being repeated, and history is being covered up.

In 2011, a new Israeli law made it illegal to mourn the Nakba: “The ‘Nakba Law’ authorises Israel’s finance minister to revoke funding from institutions that reject Israel’s character as a ‘Jewish State’ or mark the country’s Independence Day as a day of mourning.” (Al Jazeera)

If things continue this way, ignoring history and repeating the lessons of the past, dark times surely lay ahead. Indeed, this is the theme of the third section of my novel, ‘Occupied’…

This blog was written to compliment Joss Sheldon’s second novel, ‘Occupied’, which was based on the occupations of Palestine, Kurdistan and Tibet.

The ebook version of Occupied is available from this website, here.

Physical copies are available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, and all good online retailers…

Also in this blog series...

Comments ()