The world-renowned academic and American Jew, Noam Chomsky, was asked about Israeli ‘apartheid’ by Democracy Now back in 2014. This is what he said:

“In the occupied territories, what Israel is doing is much worse than apartheid. To call it apartheid is a gift to Israel, at least if by ‘apartheid’ you mean South African-style apartheid. What’s happening in the occupied territories is much worse.

“There’s a crucial difference. The South African nationalists needed the black population. That was their workforce… The Israeli relationship to the Palestinians in the occupied territories is totally different. They just don’t want them. They want them out, or at least in prison.”

The ethnic cleansing Chomsky speaks of has been covered in my first two blogs in this series, on Hebron and the Nakba. But I believe Chomsky is wrong to dismiss the apartheid completely. The apartheid that has grown up in Palestine is relevant because it is a key tool in the ongoing process of ethnic cleansing about which Chomsky speaks. It limits opportunities for locals, makes them feel like prisoners in their homes, and encourages them into exile.

In February 2015 I visited Palestine whilst researching my novel, ‘Occupied’. What follows is a simple summary of my experiences of the apartheid. It does not come close to covering the massive impact Zionist apartheid is having on millions of lives, but it does offer a snapshot into everyday life in the West Bank and East Jerusalem…

WELCOME TO ISRAEL

If the apartheid isn’t immediately obvious the moment you step into Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion airport, the soldiers who underpin it certainly are. They can be seen from pretty much every position. They interrogate me as I pass through customs control. And I am even surrounded by them as I wait to get on a bus to Jerusalem.

One soldier sits on a bench, cradling his gun on his lap, and caressing it like a mother with a baby. Three other soldiers talk. An elderly Arab couple keep their distance.

The bus to Jerusalem is modern and clean — more like a coach than any normal bus. It speeds past fields which are full of wide strips of colour, half-built concrete highways which criss-cross each other in the sky, and giant drills which turn ancient rock into feather-light dust.

Before too long the bus pulls up into Jerusalem’s central bus station; a cramped, dark underground car-park located near the centre of Israel’s capital. I collect my big backpack from the hold, put my small backpack on my front, and walk towards the street.

To leave the bus station it is necessary to walk through a small security area, which I approach alongside an Arab-looking man. I walk towards the x-ray machine, which is like any other you’d put your hand-luggage on in an airport, and am about to remove my bags.

But I am waved through.

The Arab-looking man, who only has one small bag, is stopped. I look around at him, feeling confused, but no-one else pays us any attention. Two security guards have flanked the Arab-looking man. They pat him down, interrogate him, and demand to see his identification documents.

Jewish-looking passengers, replete with varying amounts of luggage, continue past us. Soldiers, each of whom carries a gun, continue past us. They don’t even look at the security guards or the Arab-looking man. They just continue on.

I feel that I’m making a spectacle of myself, standing here like a statue, so I turn and slowly walk towards the street, where I take a tram to the Arab bus station.

I get on a bus, which is fine by most standards but nowhere nice as the inter-city bus I had been on before, and head for the West Bank.

APARTHEID WALL

As I look out of the bus’s window, the apartheid wall comes into view. It’s daunting. At eight metres tall it dwarfs almost any other wall I’ve seen in my life. The top is slightly angled, which creates and eerie shadow. My heart sinks, but the bus continues on.

It is a few days before I return to see the wall up close, near the Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem.

As I approach, smiling children ride bikes up and down a hill, waving their hands in the air, shouting ‘wahoo’; indifferent to the overbearing edifice behind them. They circle me, try to grab my bag, and ask me for shekels. They don’t give the wall a second glance.

I move on.

All is still here. An olive grove rubs up against the wall, full of rambling cacti and rocks which look like they have been spewed out the earth. A pile of rubbish burns, sending acrid grew smoke towards the heavens. Children chase chickens.

Every hundred metres or so a watch tower stands tall between the wall’s concrete slabs. Many of them have been burnt black by mischievous children. But the only other sign that this wall is not welcome takes the form of graffiti.

Someone has scrawled the word ‘Why?’ in giant letters. Someone else has painted a black and white escalator. Another piece of graffiti demands, ‘Make hummus not walls’.

This wall is crippling the economy, bankrupting businesses, splitting up families, and treating Palestinians like zoo animals in their own land. All the Palestinians can do is paint.

CHECKPOINTS

The wall, if nothing else, is a reminder to the Palestinians that the Zionists are in charge. It is not the only reminder they have to face on a daily basis. Checkpoints are everywhere, and whilst most of them are not operational, or even efficient (I’m sure any real ‘terrorist’ could easily find a way to circumnavigate most checkpoints), their very existence serves to remind the population that they could be stopped, searched, blocked, arrested or harassed at any time. And the locals are harassed at checkpoints. In the most extreme situations they are made to sit out in the sun for hours. Some Palestinians have been stripped naked at checkpoints, others have miscarried.

I meet an aid worker in Ramallah who has to go through a checkpoint every day, to get to work in Jerusalem. Despite having diplomatic stickers on her car, she is always pulled over and asked for identification, because her car has white Palestinian number plates. She must watch on whilst Israeli cars (with yellow number plates) speed past.

This is the norm. There are even separate roads for Palestinians and Israelis. The aid worker I speak to must carry two phones; one with a Palestinian number and one with an Israeli number. Israelis will not take her call if she calls them on her Palestinian phone.

The checkpoints don’t only stop people. Those in the centre of Hebron also stop ambulances and animals. As a result, the locals often miss out in vital medical attention, and can no longer use their donkeys to take their wares to market.

As an international tourist, I am not subjected to the harassment most Palestinians face at checkpoints. I am only inconvenienced on three occasions:

A soldier boards my bus and asks for ID as I make my way back into East Jerusalem.

I am questioned and searched on my way into Hebron.

And a young female soldier types my passport number into her computer at a checkpoint near Ramallah…

BORDERS

After a week in Jordan I return to Israel via the Eilat border.

I stand face-to-face with a pretty young soldier. She is petite, with freckles on her chubby cheeks. Her hair shines and her eyes glisten.

“You were in Israel before,” she says. “Where did you go?”

When I left for Jordan I was interrogated for over ten minutes, during which time it became apparent that the authorities knew I’d been through the Ramallah checkpoint. So I feel I have no choice but to tell the truth.

“The West Bank and Jerusalem,” I say.

There’s a pause. And then the interrogation begins:

“Where towns did you visit? Why did you go there? What did you do? Who did you stay with? Why aren’t you here with your parents? Why on earth would you want to spend time with the Arabs?”

The soldier’s tone is not aggressive. She’s clearly leading the conversations, but there’s a hint of intrigue in her tone. If we were in a bar, I’d say she was flirting.

After ten minutes I am asked to put my bag through an x-ray machine. My bag is swabbed and searched. Some soldiers thumb through copies of my first novel, ‘Involution and Evolution’.

I leave the room and approach a lady who is sat behind a glass window. She types my passport number into her computer, sees that I’ve been to the West Bank, and refuses to stamp my passport. I am made to wait for another ten minutes, before I am shown into the manager’s office.

The manager is a slightly jovial middle aged man. He’s muscled, with an aura of firmness and strength. His questions always have follow-ups. Whenever I answer one, he encourages me to continue talking. When he asks where I’m staying next, he takes my guide book and looks inside.

After over an hour I’m finally allowed to leave, and a couple of friendly Israelis give me a lift into town.

But, in the meantime, tens if not hundreds of other people have been allowed through. The mere fact I’d been to Palestine was enough to single me out for special treatment.

For actual Palestinians things can be far worse. Whilst Jews can claim Israeli citizenship even if they have never set foot in Israel itself, and move into settlements on Palestinian land, millions of Palestinians are currently living in exile, unable to walk on land their families have been calling home for centuries if not millennia. It is borders like this one that stop them from returning to their homes.

LEGISLATIVE APARTHEID

Whilst the apartheid wall and checkpoints may be the most visible symbols of Israeli apartheid, their images featuring on websites around the world, there is far more to this story.

You may recall the student I met in Jalazone, who featured in my blog on the Nakba. That articulate youngster spent two years in an Israeli prison without even knowing what he had been arrested for.

Such a story, on the face of it, might seem a little far-fetched. But it is far from unusual. According to Defence For Children’s report, ‘Palestinian Child Prisoners’, around seven hundred young Palestinians are arrested, detained and interrogated by the Israeli military machine each year:

“Children are commonly arrested from the family home in the hours before dawn by heavily armed soldiers. The child is painfully bound, blindfolded and bundled into the back of a military vehicle without any indication as to why or where the child is being taken. Children are commonly mistreated during the transfer process and arrive at the interrogation and detention centres traumatised, tired and alone.

“Whilst under interrogation children are subjected to a number of prohibited techniques, including the excessive use of blindfolds and handcuffs; slapping and kicking; painful position abuse for long periods of time; solitary confinement and sleep deprivation; and a combination of physical and psychological threats to the child, and the child’s family. Most children confess and some are forced to sign confessions written in Hebrew, a language they do not comprehend. These interrogations are not video recorded as is required under Israeli domestic law.

“Children as young as 12 years are prosecuted in the Israeli military courts and are treated as adults as soon as they turn 16, in contrast to the situation under Israeli domestic law, whereby majority is attained at 18.”

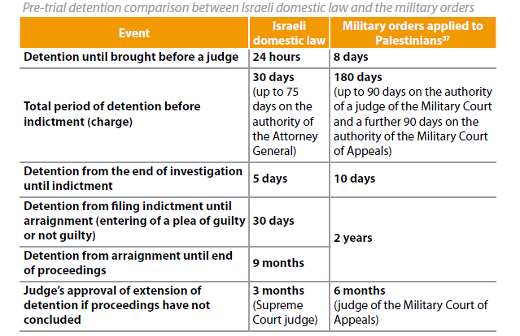

As the following chart shows, when it comes to law and justice, there’s one rule for Israeli’s and another for Palestinians:

The most common charge against children who’ve been arrested is stone throwing; a crime that carries a maximum penalty of twenty years imprisonment under Israeli Military Order 378.

Yet I repeatedly heard stories of stone throwing by Zionist settlers as I travelled around the West Bank. In most incidents, so I was told, the army did not intervene until the locals reacted, at which point it was the locals who were arrested, not the settlers.

The most horrific story I heard was from the mother in whose house I stayed whilst I visited Hebron. Her courtyard is overlooked by two high-rise sentry posts, which are manned by bored teenage soldiers.

One day, that mother was sitting in her courtyard when one such soldier decided to throw a grenade in her direction. That grenade exploded. The mother, who was heavily pregnant at the time, miscarried.

No charges were brought against the soldier. But a few years later, when the family had their house renovated, they were the ones to be punished. They were (temporarily) evicted, because it is illegal for locals to renovate their homes if they are located near to a Zionist settlement in Hebron. Meanwhile, settlers continue to live in the buildings they have stolen from the locals, without any fear of arrest or eviction.

It should be noted that those settlers are, in fact, the real criminals. The settlements they inhabit are illegal under the Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 49, which states: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.”

But Israel doesn’t appear to care for this piece of international law. Indeed, back in 1998, the Israeli Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon, encouraged his people to build more of them: “Everyone has to move, run and grab as many hilltops as they can to enlarge the settlements, because everything we take now will stay ours… Everything we don’t grab will go to them… (There) is no Zionism colonisation or Jewish state without the eviction of Arabs and the expropriation of their land.”

In the years which followed that statement, during which time seven million Palestinians lived in refugee camps — unable to return to their homes, more Israeli settlements popped up on hilltops all over the West Bank…

SETTLEMENTS

Three metre tall fences, topped off with curls of barbed-wire, surround the settlements which overlook Hebron. They swallow up fields, and reach right up to Palestinian homes. Shepherds are left with mere morsels of land on which to graze their flocks.

I show my ID to the security guard and enter.

The similarities and the differences hit me straight away.

The women still wear headscarves here, although the designs seem slightly different from those worn down in Hebron. Wild cats still wander by, as skittish as ever, but they do seem healthier. Flags still flutter, although their designs differ. Supermarkets replace markets, large concrete football pitches replace scraps of rubble-strewn ground, and empty two lane roads replace busy narrow lanes.

The only place that settlers and locals seem to mix is on the fringe of this settlement. I see one such settler shout at a Palestinian mechanic here. He has two handguns attached to his belt. Behind me, an armoured vehicle drives past.

I get into a shared taxi to visit another series of settlements, located halfway between Bethlehem and Hebron. I’m dropped off at a main junction, and start to walk down a busy road.

Rain soaks me to the bone.

Without even trying to hitch a lift, a settler stops, opens his door, and motions for me to get into his car. This young man looks a bit like a hippy. His car is a mess, as is his long hair, but he seems happy. He has a warm and gentle persona. He keeps on calling me ‘brother’.

I walk around the furthest settlement; an anonymous suburb which is wet, green and verdant. Then I am offered a lift back by a retired American engineer.

“This is my home,” he tells me. “I have waited for two thousand years to be able to live here.”

“Why did you come?” I ask.

“I’d rather work for my own country (Israel) than work hard for someone else (America),” the settler replies

This genuine, happy, friendly man guesses my hometown before he drops me off.

I enter the café attached to a vineyard which overlooks two wide roads, and have a cup of coffee which costs about ten times the price of a coffee in Hebron. The settlers can afford the higher prices — they get paid more than the Palestinians, even when they’re doing the same jobs.

I spark up a conversation with the waiter, who also seems friendly. He tells me that he feels safe in his settlement. But when I say that I’ve been staying in Hebron he seems shocked.

“Oh,” he says. “That’s not safe!”

And this is the crux of the matter. It seems to me that, deep down, the Palestinians and Israelis have a lot in common. They’re all friendly, warm and welcoming. They all just want to get on with their lives. They’ll all give you as much tea as you can drink, share a shisha pipe, and engage in conversation.

But, most significantly, they all seem to fear each other.

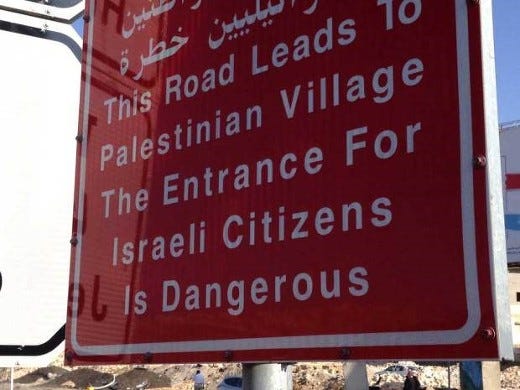

It’s not hard to see why, when even the road signs are fear-inducing. Just as most Palestinians are forbidden from entering the settlements, so most Israelis are forbidden from entering Palestinian towns. The signposts warn them: “The entrance for Israeli citizens is dangerous”.

On my last night in the West Bank I stay with a young couple in a settlement near Jerusalem. They’re like any other young couple you might meet in the west. After completing their military service they travelled.

Then they returned home to fledgling careers, with dreams of owning their own home.

This young couple are the most hospitable people I’ve met here. They drive me to their cute and cosy portacabin, which overlooks a flower-filled valley. They make me feel at home, cook for me, and let me stay for free.

After dinner we light the shisha pipe and begin to talk. It soon becomes apparent that these settlers feel that they are the victims.

The husband was made to give up his family home, and was moved out of Gaza by the Israeli government.

“What was it for?” He asks. “The Arabs are still fighting. They can’t be pleased.”

He shakes his head before he continues.

“We provide them with electricity. They owe us loads of money, but we never ask them to pay off their debts. What more can we do?”

He shakes his head again, whilst his wife begins to speak. She says that she was taught to fear Arabs whilst she was at school, although she claims that was the exception — not the norm.

“I do get scared though,” she admits. “During last June’s attacks, when rockets flew above Tel Aviv, I couldn’t sleep for a month. I lost five pounds!”

Yet when I suggest that a one-state solution could bring peace, she is adamant it’s not the answer.

“No,” she says. “We need a Jewish state to protect ourselves from another holocaust.”

And here it is again. Fear! These lovely settlers fear the Palestinians, in much the same way that the lovely Palestinians I have met fear the settlers.

I can’t help but feel the apartheid is to blame. The apartheid keeps the Israelis and Palestinians apart, such that neither group ever really gets to meet the other. Neither group gets to know the other. And so neither group is able to see that deep down, they’re not so different.

Yes, the Palestinians suffer. The Zionists hoard their water, steal their land, stop their movement, harass them at checkpoints, judge them by different legal standards, and pay them lower wages. But the settlers are suffering too. Deep down, they all share a common humanity — they all want peace. Yet most people are unable to see this, because the apartheid system divides them, and fear overcomes them.

This is the really tragedy.

This blog was written to compliment Joss Sheldon’s second novel, ‘Occupied’, which was based on the occupations of Palestine, Kurdistan and Tibet.

The ebook version of Occupied is available from this website, here.

Physical copies are available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones, and all good online retailers…

Also in this blog series...

Comments ()