The Magnificent Legacy: Importance of Palaces and Kasbahs in Moroccan History

As I stood in the shadow of towering mud-brick walls, the late afternoon sun casting an amber glow across ancient fortifications, the contrast was striking. Just days before, I had wandered through the ornate chambers of a royal palace in Fez, where intricate tilework and carved cedar ceilings spoke of unimaginable wealth and refinement. Now, facing the imposing silhouette of a desert kasbah, I was witnessing the other face of Morocco’s architectural heritage — rugged, resilient, and equally significant to understanding this nation’s fascinating history.

Morocco’s landscape is dominated by these two distinctive architectural forms — the grand palaces that anchored imperial cities and the formidable kasbahs that command strategic positions throughout the countryside. While visually different, both structures tell a complementary story of Morocco’s historical development, governance systems, defensive strategies, cultural expressions, and social organization across the centuries.

This exploration takes us through the distinct yet interconnected roles that palaces and kasbahs have played in shaping Morocco’s historical narrative. From seats of royal power to defenders of trade routes, from centers of artistic patronage to symbols of regional authority, these structures have been silent witnesses to Morocco’s evolution. Together, they form an architectural language that speaks volumes about the nation’s past and continues to define its cultural identity today.

“If you would like to explore Morocco in greater depth, I recommend checking out this [digital guide about Morocco] https://payhip.com/MoroccoTravelGuide. Please note that this is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.”

What Are Moroccan Palaces? Seats of Power and Splendor

A Moroccan palace, or Dar al-Makhzen (literally “House of the Treasury” or “House of Government”), represents far more than merely a luxurious royal residence. These magnificent complexes served as the physical embodiment of the monarchy’s power, housing not just the royal family but an entire apparatus of governance, ceremony, and cultural patronage.

Historical Functions:

Royal residence: First and foremost, palaces provided lavish living quarters for the sultan and his extensive family, including separate sections for the royal harem. These private spaces were often the most opulently decorated areas, shielded from public view.

Center of government (Makhzen) & administration: The term Makhzen (from which the word “palace” derives) originally referred to the Moroccan state treasury but evolved to describe the entire governing apparatus. Palaces contained audience halls where the sultan would receive delegations, administrative offices, and meeting chambers for royal councils.

Display of wealth, power, and dynastic legitimacy: Through their scale, decoration, and ceremonial spaces, palaces provided physical proof of the sultan’s claim to rule. The architecture itself became propaganda, reinforcing the monarchy’s prestige among both subjects and foreign visitors.

Hub for arts, culture, and diplomacy: Palaces were centers of learning, artistic patronage, and cultural development. They housed libraries, supported artisans, and provided venues for diplomatic receptions that shaped Morocco’s relations with other powers.

Key Architectural Characteristics:

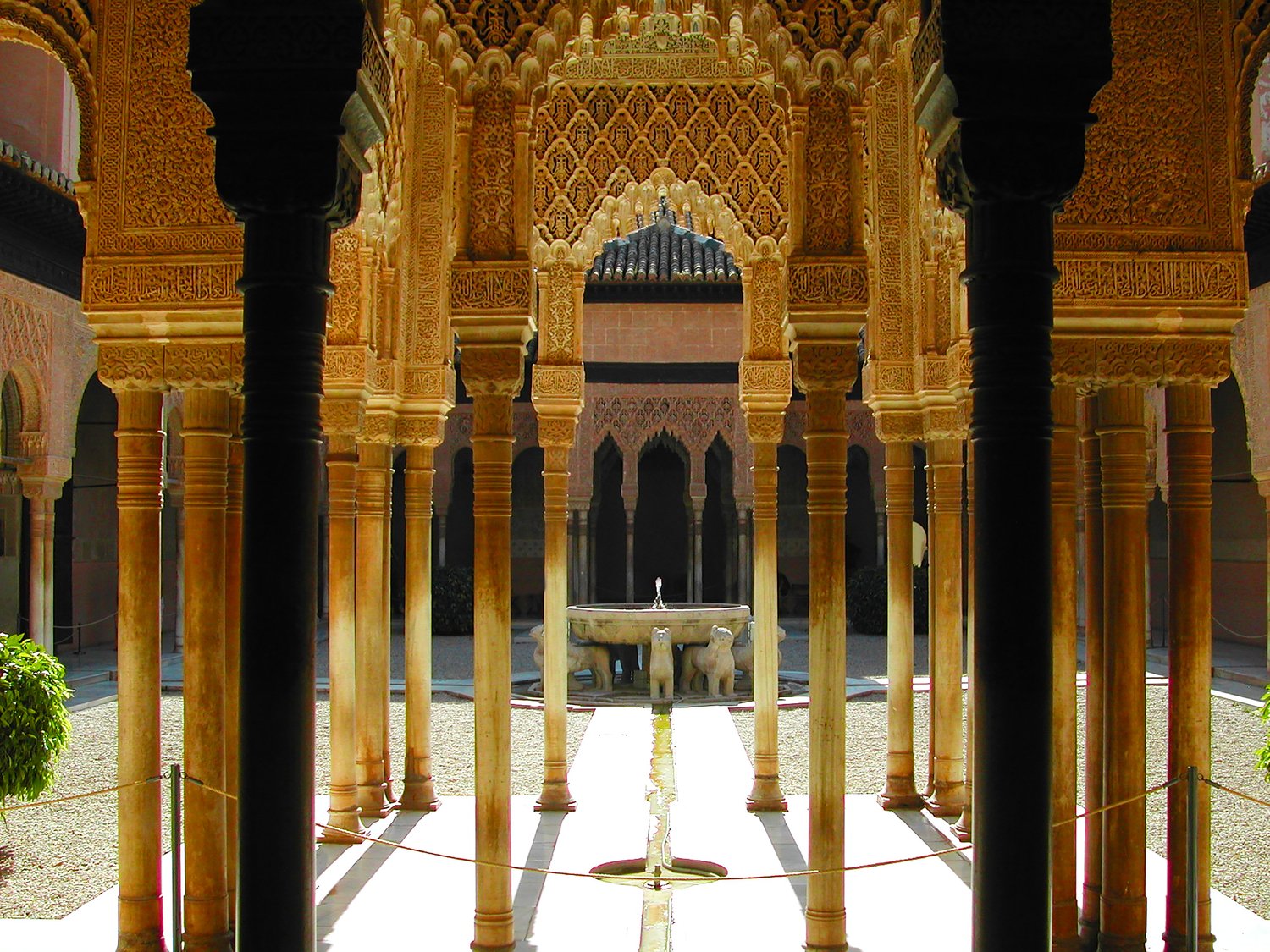

- Intricate decorative elements:

- Zellij (geometric mosaic tilework) in vibrant blues, greens, and terracotta

- Carved plaster (stucco) featuring calligraphy and arabesque patterns

- Intricately carved cedar wood ceilings and doors

- Muqarnas (honeycomb-like decorative vaulting)

- Spatial organization:

- Expansive courtyards with gardens, orange trees, and fountains

- Riad patterns (interior gardens with four-part division symbolizing paradise)

- Strict separation between public (salamlek) and private (haremlek) spaces

- Mechouar (ceremonial courtyard or plaza) for public appearances and ceremonies

- Structural elements:

- Monumental gateways often featuring copper or brass doors

- Colonnaded arcades with horseshoe arches

- Central location within imperial cities, often surrounded by their own walls

- Multiple self-contained pavilions rather than one massive structure

The Historical Importance of Palaces in Morocco

Throughout Morocco’s dynastic history, palaces have been instrumental in consolidating power, projecting authority, and establishing the cultural identity of each ruling family. As dynasties rose and fell, each left their architectural mark through palace construction or expansion.

The Almoravids (1062–1147) and Almohads (1147–1269) established the early tradition of palace building within the context of creating new imperial cities. Their architectural programs helped transplant and adapt Andalusian artistic influences while establishing Morocco as a center of Islamic power independent from eastern caliphates.

The Marinid dynasty (1269–1465) elevated palace architecture to new heights, particularly in Fez, where they expanded the palace complex and established madrasas (Islamic schools) nearby, creating an integrated center of power and learning. Their palace-building program reflected a dynasty seeking legitimacy through cultural and religious patronage.

The Saadian period (1549–1659) represents a golden age of palace construction, particularly in Marrakech. Following their victory over Portuguese invaders, the Saadians channeled new wealth into monumental architecture that demonstrated both their military success and their religious legitimacy as sharifs (descendants of the Prophet Muhammad).

The current Alaouite dynasty (1666-present) has maintained, restored, and expanded the palace tradition over centuries. Their continuous occupation of royal palaces provides a direct link between historical and contemporary Morocco.

Spotlight on Iconic Palaces:

Royal Palace of Fez (Dar al-Makhzen): Dating primarily from the 14th century but continuously modified, this sprawling complex covers nearly 80 hectares in the heart of Fez. Though its interior remains closed to the public (as it still serves as a royal residence when the king visits), its massive brass doors and imposing façade demonstrate how palaces functioned as symbols of monarchy. Its continuous use over centuries highlights the remarkable continuity of Moroccan royal traditions.

El Badi Palace, Marrakech: Built in the 1570s by Saadian Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur following his victory at the Battle of the Three Kings, this once-spectacular palace was deliberately constructed to awe visitors with its sheer scale and luxury. With a name meaning “The Incomparable,” it featured over 300 lavishly decorated rooms, pools reflecting pavilions, and extensive use of imported materials including Italian marble and gold from Sudan. Though now in ruins (having been stripped of its treasures by subsequent rulers), El Badi illustrates how palaces functioned as statements of international prestige and military success.

Bahia Palace, Marrakech: Constructed in the late 19th century by Si Moussa (grand vizier to Sultan Hassan I) and later expanded by his son Ba Ahmed (who became grand vizier to Sultan Abdelaziz), this palace demonstrates the extension of palace-building tradition beyond the monarch himself. The name “Bahia” means “brilliance,” and its 150 rooms showcase the finest Moroccan craftsmanship of the period. Its history reveals how architectural patronage reflected the complex power dynamics of pre-colonial Morocco, as court officials sought to establish their own legacy through monumental construction.

Royal Palace of Rabat: As Morocco’s current official royal palace, this complex represents the adaptation of historical traditions to modern governance. Established after France declared Rabat the capital of the protectorate in 1912, it stands on the site of earlier royal buildings dating to the Almohad period. Today, it houses both the personal residence of King Mohammed VI and numerous administrative and ceremonial facilities. Its continuing function illustrates how the palace tradition remains central to Morocco’s national identity and governance.

What Are Moroccan Kasbahs? Fortresses of Defense and Community

The term “kasbah” (from Arabic qasaba, meaning citadel) refers to a fortified structure that served as both defensive installation and center of local authority. Usually constructed from locally-sourced materials, these imposing structures rise from Morocco’s diverse landscapes, from mountain passes to desert oases and coastal promontories.

It’s worth noting the distinction between kasbahs and ksour (singular: ksar) — while sometimes used interchangeably, a kasbah typically refers to a single fortified structure housing a leader and garrison, while a ksar describes an entire fortified village or settlement. Many famous “kasbahs” like Ait Benhaddou are technically ksour, though they contain prominent kasbahs within them.

Historical Functions:

Defense against external threats: Kasbahs were built to withstand attacks from rival tribes, nomadic raiders, or foreign invaders. Their thick walls, minimal exterior openings, and strategic positioning on high ground or at narrow passages provided security in often tumultuous regions.

Control over trade routes: Many kasbahs were strategically positioned along lucrative trade routes, particularly those connecting sub-Saharan Africa to northern Morocco. They secured passage for caravans carrying gold, salt, slaves, and other valuable commodities across difficult terrain.

Administrative centers for local governance: Kasbahs housed the caids (regional governors) or local chieftains who represented central authority or maintained independent control in rural areas. From these fortified seats, they collected taxes, administered justice, and maintained order.

Residences for ruling families: Besides their defensive function, kasbahs contained living quarters for the local ruler and his family. The most impressive kasbahs featured interior courtyards, private quarters, and reception rooms that mimicked palace design on a smaller scale.

Community refuge: During times of danger, kasbahs could shelter the surrounding population and their livestock, providing a defensible space for entire communities during conflicts or raids.

Key Architectural Characteristics:

- Construction materials and techniques:

- Rammed earth (pisé) or adobe brick construction, using locally-sourced materials

- Walls that taper upward (wider at base, narrower at top) for structural stability

- Minimal exterior decoration, emphasizing function over form

- Natural pigments in the soil giving the characteristic red or ochre coloration

- Defensive elements:

- High walls (often 10 meters or more) with crenellated tops for defensive positioning

- Corner towers (borj) providing 360-degree surveillance

- Narrow, easily defensible entrances, sometimes with bent passageways

- Strategic positioning on elevated ground or controlling narrow valleys

- Interior organization:

- Central courtyard providing light and ventilation

- Granaries and storage for withstanding sieges

- Multi-story construction with increasingly private spaces on upper levels

- Rooftop terraces for surveillance and additional living space in hot weather

The Historical Importance of Kasbahs in Morocco

The proliferation of kasbahs across Morocco’s landscape reflects a historical reality of decentralized power and the necessity of local defense in regions distant from imperial capitals. These structures tell a story complementary to that of royal palaces — one of regional autonomy, adaptation to harsh environments, and the complex relationship between central authority and local governance.

Kasbahs were particularly vital during periods of dynastic weakness when central control fragmented, allowing local powers to assert independence. The areas most densely populated with kasbahs — particularly the pre-Saharan regions and Atlas Mountains — were precisely those where the sultan’s authority was most tenuous and where local leaders (caids) exercised considerable autonomy.

The famous “Route of a Thousand Kasbahs” winding through southern Morocco’s valleys illustrates how these structures controlled movement through difficult terrain. By commanding mountain passes and river crossings, kasbahs established control points that enabled regional powers to profit from and regulate trans-Saharan trade.

Kasbahs also reflect Morocco’s Amazigh (Berber) heritage and tribal organization. While palaces generally represented Arab-influenced governance traditions centered in imperial cities, kasbahs often embodied Amazigh concepts of territorial control and communal defense. Their construction techniques — particularly the use of rammed earth (pisé) — represent indigenous architectural knowledge perfectly adapted to local environmental conditions.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, powerful caids like Thami El Glaoui (Pasha of Marrakech) used kasbahs as bases to build regional power networks that sometimes rivaled central authority. The grandeur of kasbahs like Telouet reflects how successful local leaders could accumulate wealth and power comparable to royal resources.

Spotlight on Iconic Kasbahs:

Ait Benhaddou: This UNESCO World Heritage site near Ouarzazate stands as perhaps Morocco’s most famous kasbah complex (technically a ksar containing multiple family kasbahs). Its striking stepped construction rising from the valley floor dates primarily from the 17th century, though its foundations are much older. As a fortified trading post controlling routes between Marrakech and the Sahara, it exemplifies how kasbahs established control points along vital commercial arteries. Its well-preserved state offers visitors an unparalleled glimpse into traditional defensive architecture, which explains its frequent appearance in films from “Lawrence of Arabia” to “Game of Thrones.”

Telouet Kasbah: Located high in the Atlas Mountains, this once-magnificent kasbah served as the seat of the powerful El Glaoui family, who controlled the strategic Tizi n’Tichka pass between Marrakech and the pre-Saharan regions. Built primarily in the 19th century, it represents the blurring of lines between kasbah and palace. While its exterior maintains the austere defensive appearance typical of kasbahs, its interior reception halls feature palace-worthy decoration with intricate zellij, painted cedar ceilings, and stucco work. The kasbah’s history illustrates how local leaders could amass tremendous power — the Glaouis collaborated with French colonial authorities, allowing Thami El Glaoui to become one of Morocco’s richest and most powerful figures until independence.

Kasbah of the Udayas, Rabat: Standing guard at the mouth of the Bou Regreg River, this kasbah demonstrates how these structures adapted to coastal defense needs. Originally built in the 12th century by the Almohads, it was designed to protect against both sea-based invasions and rebellions from neighboring settlements. Its strategic position controlling access to the river made it vital for both military and commercial purposes. Unlike desert kasbahs built of earth, it features stone construction more suitable to the coastal climate. Its subsequent history of occupation by various groups, including Andalusian refugees in the 17th century, shows how kasbahs could be repurposed over centuries while maintaining their defensive character.

Taourirt Kasbah, Ouarzazate: Another seat of the powerful Glaoui family, this massive complex with over 300 rooms dramatically demonstrates how kasbahs functioned as centers of regional governance. Its imposing silhouette dominates Ouarzazate, a city that developed largely around this administrative center. Built primarily in the 19th century, its size and complexity — with numerous interconnected buildings rather than a single structure — show how kasbahs evolved to accommodate expanded administrative functions beyond pure defense. Its location made it a critical control point for caravan routes connecting Marrakech to the desert regions and beyond to West Africa.

Intertwined Histories: Palaces and Kasbahs Shaping Morocco

The parallel development of palaces and kasbahs reveals a fundamental duality in Moroccan governance and social organization — a push-pull between centralized royal authority and decentralized regional power. This architectural dichotomy reflects Morocco’s complex historical reality as a nation where strong sultans periodically extended central control, only to see it fragment during weaker reigns when local powers reasserted autonomy.

The relationship between palace and kasbah can be understood as a physical manifestation of the traditional Moroccan political concept of bled el-makhzen versus bled es-siba — lands under direct government control versus “lands of dissidence” with greater independence. Palaces represented the sultan’s direct authority in imperial cities and their immediate surroundings, while kasbahs embodied the negotiated power of rural areas where geography and distance necessitated local governance structures.

This relationship was not simply antagonistic but symbiotic. Effective sultans recognized they could not directly control vast territories and instead appointed loyal caids who ruled from kasbahs, creating a network of regional power centers that acknowledged royal authority while maintaining local autonomy. The most successful dynasties mastered this balance, using kasbahs as extensions of palace power rather than challenges to it.

The architectural differences between palaces and kasbahs reflect their differing priorities. Palaces emphasized splendor, artistic refinement, and ceremonial space to reinforce royal legitimacy through cultural display. Kasbahs prioritized defensive capability, strategic position, and functional governance in often hostile environments. Yet both served as symbols of authority to their respective populations.

These structures also represent different aspects of Morocco’s identity — palaces generally embodying the Arab, Islamic, and Mediterranean influences prevalent in imperial cities, while kasbahs often reflected Amazigh (Berber) architectural traditions and social organization in rural areas. Together, they demonstrate the cultural synthesis that defines Moroccan identity.

Interestingly, many structures blur the boundaries between palace and kasbah. Royal citadels like the Kasbah of the Udayas combine defensive functions with royal residences. Conversely, powerful caids created kasbahs with palace-like interior decoration, as seen at Telouet. This architectural hybridization mirrors the fluid nature of power relations throughout Moroccan history.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries — during the pre-colonial period and subsequent French Protectorate — saw this relationship dramatically tested. Powerful caids, particularly in southern Morocco, built increasingly elaborate kasbahs and accumulated unprecedented wealth and authority, often with foreign support. This period produced some of Morocco’s most spectacular kasbahs, which ironically coincided with the traditional system’s coming demise.

Today, both palaces and kasbahs remain essential to understanding Morocco’s historical narrative. Royal palaces continue to function as centers of governance and national ceremony, maintaining a direct line of continuity from historical kingdoms to the modern nation-state. Kasbahs, though largely no longer serving their original defensive and administrative purposes, have become critical heritage sites and tourism draws that showcase regional identities and traditional architecture.

Visiting Palaces and Kasbahs Today: Experiencing History

Travelers to Morocco have unparalleled opportunities to experience these architectural treasures firsthand, though with differing levels of access. While functioning royal palaces remain closed to the public, many historical palaces have been preserved as museums or cultural venues. Kasbahs, meanwhile, offer some of Morocco’s most immersive historical experiences, allowing visitors to walk the same ramparts and passages that once secured these strategic strongholds.

A thoughtful itinerary combining palace and kasbah visits provides deeper insight into Morocco’s historical complexity than either could alone. Standing in the refined courtyard of Marrakech’s Bahia Palace before traveling to the earthen fortresses of the Draa Valley tells a more complete story than either experience in isolation.

Visitors to palaces can appreciate the height of Moroccan decorative arts and understand how architecture reinforced royal authority through sheer beauty and refinement. The meticulous restoration of sites like the Bahia Palace allows guests to envision the settings for historical court ceremonies and diplomatic receptions that shaped the nation’s destiny.

Kasbah exploration offers a different but equally valuable historical perspective. Climbing the narrow passages of Ait Benhaddou or surveying the landscape from the towers of Amridil Kasbah helps visitors understand the strategic thinking behind these placements and the defensive concerns that shaped daily life in regions far from imperial centers.

Many kasbahs also offer opportunities to experience traditional construction techniques firsthand. The ongoing restoration of these earthen structures, often using original methods, provides a living museum of architectural practices perfectly adapted to local environmental conditions — an increasingly valuable lesson in sustainable building practices.

When visiting these sites, responsible tourism practices are essential to their preservation. The fragile nature of many kasbahs, particularly those constructed from rammed earth, makes them vulnerable to increased foot traffic and environmental changes. Supporting conservation efforts through entrance fees and respecting site guidelines helps ensure these irreplaceable monuments survive for future generations.

The Enduring Legacy of Morocco’s Palaces and Kasbahs

The architectural heritage of Morocco’s palaces and kasbahs transcends mere historical interest — it remains foundational to the nation’s cultural identity and self-understanding. These structures stand as physical embodiments of Morocco’s unique historical development, which maintained independence and cultural continuity despite numerous challenges over the centuries.

Palaces, with their refined artistic traditions and ceremonial spaces, remind us how Morocco’s rulers consistently reinforced their legitimacy through cultural patronage and architectural splendor. The continued use of royal palaces for state functions demonstrates the remarkable continuity of governance traditions from medieval sultanates to the modern constitutional monarchy.

Kasbahs, rising from landscapes that might otherwise seem inhospitable, testify to the resourcefulness of communities that created defensible spaces from the simplest materials. Their strategic placement mapping ancient trade routes reveals economic networks that connected Morocco to sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean, and beyond long before modern globalization.

Together, these architectural forms tell a story of a nation defined by both unity and diversity. The tension between centralized authority and regional autonomy, between urban refinement and rural pragmatism, between Arab and Amazigh traditions — all are written into the very stones and earth of these structures. Their preservation allows each generation to reconnect with this complex legacy.

In a rapidly changing world, Morocco’s palaces and kasbahs offer tangible links to a past that continues to inform national identity. Whether standing in the ornate reception hall of a palace or atop the windswept ramparts of a desert kasbah, visitors encounter not just historical curiosities but living monuments to enduring cultural values and ingenious adaptation to challenging circumstances.

The magnificence of Morocco’s architectural heritage — from the sublime geometry of palace zellig to the earthy pragmatism of kasbah construction — reminds us that understanding history requires appreciating both the centers of power and the frontiers, both the exceptional and the everyday, both the ideal and the practical. In this complementary relationship between palace and kasbah, we find the true story of Morocco’s remarkable historical journey.

“The palace and the kasbah represent two faces of the same historical coin — one showcasing the refinement and cultural achievement that centralized power could produce, the other demonstrating the pragmatic adaptations required to maintain authority across vast and challenging landscapes.” — Dr. Fatima Mernissi, Moroccan historian

Did you know? The rammed earth construction technique used in kasbahs creates walls that naturally regulate temperature — keeping interiors cool during scorching summer days and relatively warm during cold desert nights. This sustainable building method requires minimal resources while providing maximum comfort in extreme climates.

For travelers interested in experiencing both the splendor of palaces and the rugged beauty of kasbahs, consider an itinerary that connects Morocco’s imperial cities with the southern routes. Begin in Rabat or Fez exploring palace architecture before journeying south through the Atlas Mountains, where kasbahs command strategic passes, and continue to the pre-Saharan regions where some of the most spectacular fortress complexes rise from desert landscapes.

“For those interested in learning more about Morocco’s hidden gems, I have included a digital guide below. It’s an affiliate link, and any support is greatly appreciated!”

https://payhip.com/MoroccoTravelGuide