In a post-pandemic world, health financing is being pulled in two directions.

On the one hand, governments face tighter fiscal space, rising debt, and greater pressure to deliver on universal health coverage. On the other, new actors — from private investors to philanthropic funds — are reshaping how health systems are funded through blended finance models and impact-driven capital.

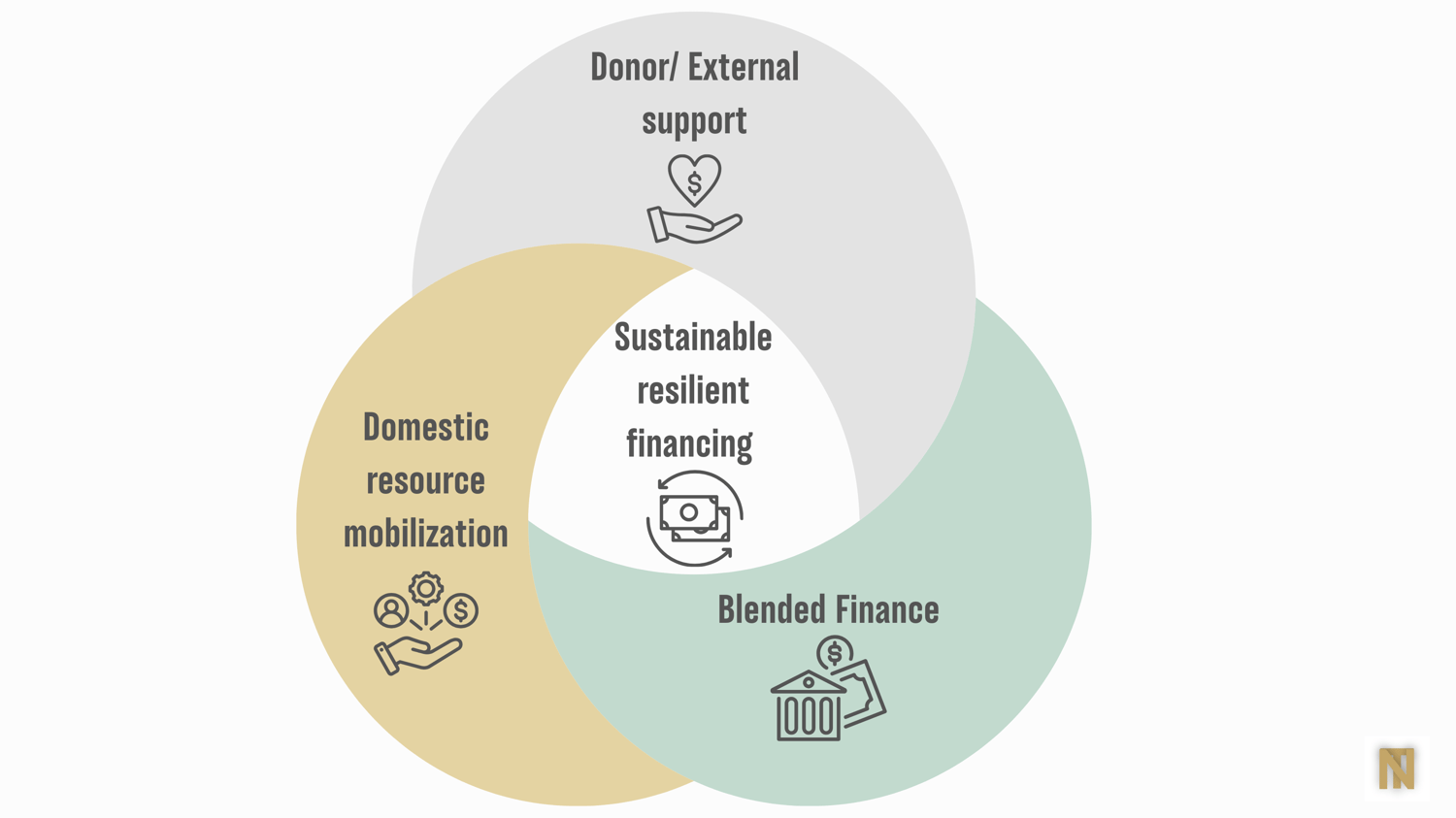

But while blended finance offers exciting potential, it is not a substitute for domestic resource mobilization (DRM). In fact, the most resilient systems rely on a combination of both — external capital to spark innovation and scale, and domestic investment to sustain and anchor progress.

Blended Finance: What It Is — and Where It Works

Blended finance uses concessional funds (often from donors or development banks) to attract additional private capital toward public health priorities — effectively de-risking investment. When structured well, it can catalyse innovation and bring in expertise and financing that wouldn’t otherwise be available.

Examples include:

- Gavi’s International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which uses long-term donor pledges to issue bonds on capital markets, accelerating vaccine access.

- The Global Financing Facility, blending grants with loans to fund reproductive, maternal, and child health services in LMICs.

- PPP diagnostic centers in Ghana, where government and private sector co-invested to increase access to imaging services.

But Innovation Does Not Replace Ownership

What blended finance can do is exciting. But what it cannot do — and should not be expected to — is replace the foundational role of domestic financing.

Resilient health systems are built when countries:

- Allocate consistent health budgets

- Integrate health into broader economic and tax reform strategies

- Mobilize resources in ways that reflect local priorities and accountability

Countries such as Thailand, Rwanda, and Kenya offer compelling examples of DRM in action — from sin taxes to health insurance expansion — with long-term health improvements to show for it.

A Smarter, Balanced Financing Model

We should not treat blended finance and DRM as competing models. Instead, we should ask: How do we design health financing strategies that pair catalytic investment with long-term sustainability?

Some principles:

- Use blended finance where it adds value, especially in infrastructure, digital health, or scaling innovations.

- Ensure domestic financing remains the core engine for service delivery and governance.

- Embed equity and sustainability into all financing structures from the start.

As we navigate shrinking aid budgets and rising demands, the real challenge is designing health financing strategies that are sustainable, equitable, and resilient — and rooted in local realities.

I would love to hear from those working on the ground:

What would you prioritize right now — expanding domestic investment, exploring blended finance models, or something else entirely?

And what has worked (or hasn’t) in your context?

Further Reading & Resources

If you would like to explore this topic further, here are some great places to start:

- OECD (2020). Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries. Read here

- BMJ Global Health (2022). Innovative financing in global health: Shifting strategies and emerging trends. Read here

- World Bank (2023). Domestic Resource Mobilization for UHC: Country Case Studies. Read here

- The Global Fund (2022). Innovative Financing Instruments and Approaches. Read here

- GFF Knowledge Series. Blended Finance: A Health Systems Perspective. Read here

Comments ()