In 2020, Zimbabwe agreed to compensate local white farmers, whose land was taken by the government from 2000 onwards to resettle black families, in one of the most emotive and divisive policies from Zimbabwe.

While foreign white farmers were allowed to apply to get seized land back, numbers show they preferred to be compensated instead.

After several litigations by the deposed farmers in Zimbabwean, South African and international courts, and multi pronged imposition of sanctions by western nations, like the United Kingdom, the USA, the UE and others, the government eventually capitulated and agreed to compensate.

Hence this 2023 US$3.5 billion 'fast track' agreement for the white ex-farmers in compensation for expropriated land, with the African Development Bank agreeing to help raise the requisite funds. The government also offered to return land to foreign nationals whose farms were seized under international agreements.

Previous court judgements

Highlight judgements from court cases by the white farmers are as follows:

> In 2008 Zimbabwe was ordered by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Tribunal to restore the land rights of 78 white farmers and to compensate them for their losses. By default, opening the door for around 4,000 other equally deprived farmers tosue for benefits as well. Zimbabwe refused to comply with the ruling and withdrew from being a member of the tribunal in 2014.

> In 2010 Zimbabwe was ordered by the High Court of South Africa to pay US$28.5 million to yet another group of these farmers, comprising of 40 members. Zimbabwe lost its appeal in 2013 and had to sell a property owned by its government in South Africa to pay for the compensation.

> In 2015 Zimbabwe was ordered by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in 2015 to pay $195 million to a group of Dutch farmers whose land was seized under bilateral investment treaties. The ICSID is an international arbitration institution established in 1966 for legal dispute resolution and conciliation between international investors and the United States of America (USA). It is part of and funded by the World Bank Group and is headquartered in Washington, D.C., in the USA. It is from this judgement that Zimbabwe agreed to pay the amount in 2019, culminating in the 2020 agreement to compensate all prejudiced farmers to the tune of US$3.5 billion

Facts of the current agreement

The facts to the deal are as follows;

> The Zimbabwean government agreed to pay US$3.5 billion to local white farmers only for seized infrastructure such as buildings, equipment and dams on the farms. The compensation does not cover the value of the land itself.

> The government offered to return land to foreign white farmers whose seized farms were covered by international agreements, such as bilateral investment treaties or regional trade agreements. Alternatively, they could opt for compensation or land swaps.

> The government altered the original compensation period from the initially agreed 20 years to a new “fast tracked.”

> Also, the initial proposal was to fund this process through issuing treasury bills, but the African Development Bank (AfDB) has offered to assist raise the requisite $3.5 billion through a “front load” process. We will discuss that shortly under "The economic fundamentals" below.

The Politics of Land Repossession in Zimbabwe: A Historical Perspective

> The land question in Zimbabwe has its roots in the colonial era, when the British South Africa Company (BSAC) invaded the territory in 1890 and dispossessed the indigenous people of their land and resources. The BSAC granted large tracts of land to white settlers, who established commercial farms and mines. The native population was confined to overcrowded and infertile reserves, where they were subjected to taxation, forced labor, and racial discrimination.

> The land dispossession sparked several uprisings by the indigenous people, such as the First Chimurenga (1896-1897) and the Second Chimurenga (1964-1979), which aimed to reclaim their land and sovereignty from the colonial regime. The Second Chimurenga, also known as the liberation war, resulted in the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980, after a protracted armed struggle by the nationalist guerrillas against the white minority government of Rhodesia.

> The Lancaster House Agreement of 1979, which paved the way for Zimbabwe's independence, included a provision for land reform, whereby the British government would fund the purchase of land from willing white sellers and redistribute it to landless black peasants. However, this process was slow and inadequate, as it was constrained by a clause that protected property rights for ten years after independence. Moreover, most of the land acquired by the state was allocated to political elites, army officers, and civil servants, rather than to the landless masses or the war veterans who had fought for liberation.

> By the year 2000, when the fast-track land reform program began, over 70% of land, most of it prime fertile land, was in the hands of only 4000 white minority farmers in a country of 12.6 million people. The liberation war veterans, who had been marginalized and neglected to this point, were now clamouring for land as well, saying that was one of the main reasons they went to war in the first place. One ridiculous example is reported story of one family, with a well known name in diamonds in the region, owning land the size of Belgium in a country only nine times bigger than Belgium itself ,and yet not having purchased it, but inherited it as colonialism spoils.

> The “fast-track land reform program” involved the violent and haphazard occupation of white-owned farms by war veterans and other landless people, with the support and encouragement of President Robert Mugabe and the ruling party, ZANU-PF. The program was justified as a way of correcting historical injustices and empowering the black majority. However, it also had political motives, as it was seen as a way of mobilising support for ZANU-PF ahead of the 2000 parliamentary elections and weakening the opposition parties that had emerged strong from the civil society movement of that time.

> The land seizures provoked the wrath of western nations, especially Britain and its allies, who imposed economic sanctions on Zimbabwe and accused President Mugabe of violating human rights and democracy. Perhaps they were miffed at the idea of their kith and kin losing land, and even more importantly, balked at the idea of other African countries following this example and re-appropriating land in their own countries. Either way, Zimbabwe’s land reclamation method provided for a reason to impose those sanctions.

Either way, the sanctions have taken a toll on the country and it will surprise few people that Zimbabwe has somewhat been dragged to this negotiation table kicking and screaming. No surprise also that some affected white farmers do not believe Zimbabwe, even after putting pen to paper, will make good on this promise. Yet, were it to hold its end of the bargain, they still feel shortchanged as they are only being compensated for developments made on the land, only. Not the land itself.

Neither are the newly resettled farmers excited at the idea of spending he equivalent of almost half the 2022 national budget on farmers who had a 100 years of free land tillage, accumulating wealth from that land they never purchased, yet and today feel entitled to proceeds of its disposal. This is at at time they, as “new farmers” are seeking funding from the government to establish their farming as bonafide businesses.

The economic fundamentals

On the one hand, This US$3.5 billion agreement could help restore trust and confidence among Zimbabwe’s domestic and foreign investors, improve property rights and contract enforcement, and attract more capital inflows and development assistance.

On the other hand, it could also pose fiscal and debt sustainability risks, increase social tensions and inequality, and divert resources from other pressing needs such as health, education, and infrastructure.

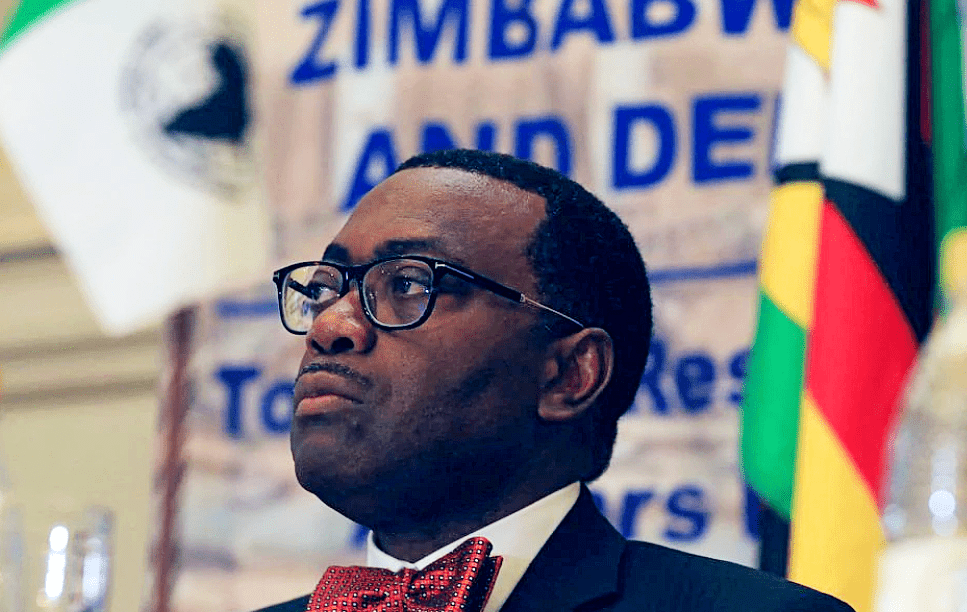

African Development Bank proposes a 'fast track' compensation programme. The president of the bank, Dr. Akinwumi Adesina's announcement did not include details of the proposed instruments that will be deployed to amortise this debt. This was after the affected farmers turned down an initial deal to receive payment via Zimbabwe treasury bills.

The AfDB president is co-chairing a process with former Mozambican President, Joaquim Chissano. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and other creditors, are also part of the process as they are the main holders of Zimbabwe's external debt, which amounts to US$8.3 billion of a total US$14 billion, as of September 2022.

They have been engaging with Zimbabwe on a staff-monitored program (SMP) since 2019, which aims to support the implementation of macroeconomic and structural reforms to restore fiscal and debt sustainability, rebuild foreign exchange buffers, and foster governance and transparency.

Over and above the farmers debt, the process aims to clear US$6 billion of external debt arrears and also include reforms to the exchange rate and centralbank, which Adesina previously said has a quasi-fiscal role that fuels inflation.

And as economists we have been advocating for the removal of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s Forex Auction system and the overhaul of the central bank operations, saying so time without number. EG:

1. https://www.thesouthernafricantimes.com/economics-of-politics-zimbabwes-reserve-bank-needs-autonomy/

Zimbabwe, which has this reported US$14 billion in external debt as of September 2022, has not been able to secure financing from the likes of the IMF in more than two decades due to its arrears. Dr. Adesina said that 91% of Zimbabwe's multilateral debt and 61% of its bilateral debt is in arrears.

My Macro-economic perspective

The key question is how to finance the compensation payments without jeopardising fiscal and debt sustainability, as Zimbabwe’s economy is currently facing a few headwinds.

As alluded to above, the AfDB's proposal would be "fast tracked and front loaded" using financial instruments that leverage the capital markets without adding debt to Zimbabwe. However, the details of these instruments are not clear, and they may still entail some costs and risks for the government and the economy.

One possible option is to issue bonds or securities that are backed by future revenues from natural resources or other sources. This would allow the government to raise funds upfront without increasing its debt stock, but it would also imply giving up some of its future income streams and exposing itself to market fluctuations and exchange rate risks.

Another possible option is to use special purpose vehicles or trust funds that pool resources from various sources, such as donors, creditors, private investors, government equity or some kind of a diaspora bond from remittances. This would help diversify the financing sources and reduce the burden on the government, but it would also require strong governance and transparency (and trust) mechanisms, plus coordination among multiple stakeholders.

The impact of the compensation payments on the economy would depend on several factors, such as the size per annum, relative to competing demands, timing, and distribution of the payments; the response of the recipients; and the macroeconomic policy framework.

The payments might well have a positive effect on aggregate demand and output if they stimulate consumption and investment by the ex-farmers or their beneficiaries. However, I would not lean on this as most of these ousted farmers are already out of Zimbabwe so it is far fetched to expect them to spend their emoluments in Zimbabwe at all.

The payments could also have a positive effect on aggregate supply and productivity if they come with a clauses that improve/guarantee land tenure or security for current incumbents, which will improve agricultural efficiency.

However, these effects may be limited or offset by other factors, such as inflationary pressures (which has reared its ugly heard forcefully in the pat month leading to signing of this revised agreement), crowding out of private sector credit, exchange rate appreciation through revamping or outright discarding the RBZ Forex Auction System, or reduced fiscal spending, as obtained in 2022 where 46% of the national budget when to infrastructure expenditure, in the process soaked the economy with excess liquidity.

On a socio-economic note, the compensation payments will likely have distributional consequences for income and wealth inequality. The ex-farmers, likely, are already wealthier than the average population, so transferring resources to them easily increases inequality. Furthermore, since they are mostly based outside Zimbabwe, this is akin to wealth externalisation at an industrial scale.

Moreover, the payments could create resentment among the beneficiaries of the land reform program or other groups that may feel excluded or disadvantaged by the deal, not to speak of feeling disenfranchised and un-prioritised. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the compensation process is fair, transparent, inclusive, and consistent with broader social objectives.

In conclusion, Zimbabwe's move to compensate white ex-farmers is a complex and delicate issue that requires careful analysis and management. It could offer an opportunity to improve economic performance and prospects, allow for re-engagement with the international community and lead to repeal of economic sanctions, but it could also entail significant challenges and trade-offs.

The AfDB's proposal to use “innovative financial instruments”, whatever these are, to fund the compensation without adding debt to Zimbabwe is a welcome initiative that deserves further exploration and elaboration. We should be aware it is not a panacea, and it needs to be complemented by sound macroeconomic policies and structural reforms, not least of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe itself, to address Zimbabwe's underlying economic problems.