The capital markets of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have been hailed as some of the best performing sectors in the region, attracting foreign investors and generating impressive returns.

Be that as it may, a closer look at the performance and impact of these markets reveals a stark contrast between the apparent prosperity of the financial intermediaries on one hand and the persistent challenges faced by the real economy and the ordinary citizens on the other.

In this article we examine the state of the capital markets in SSA, their role in supporting economic development and social welfare, and the potential reforms that could enhance their effectiveness and inclusiveness.

Capital markets are broadly defined as the markets where financial securities, such as stocks, bonds, and derivatives, are issued and traded. They provide a platform for mobilising savings, allocating capital, diversifying risk, and facilitating transactions. They also play a crucial role in not only providing a conduit for smooth flow of value (money) but also transmitting monetary policy, influencing exchange rates, and shaping expectations.

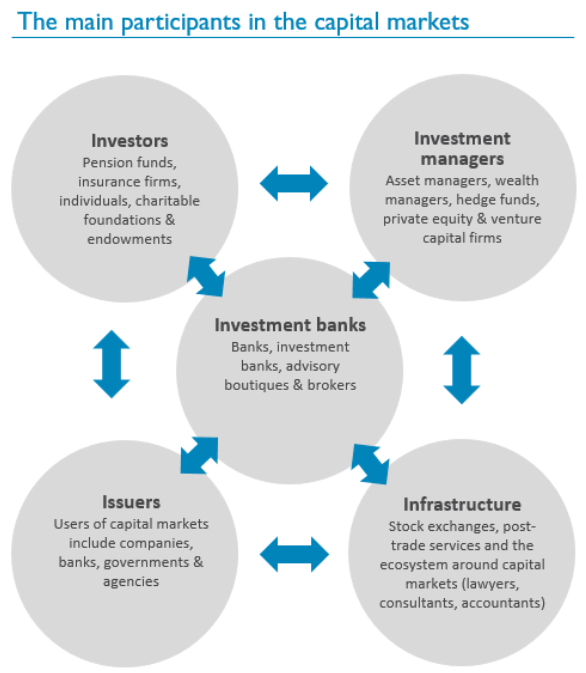

Players in the capital markets and their links

In SSA, capital markets are composed mainly of stock exchanges, banks, insurers and bond markets, among others, with varying degrees of development and sophistication across countries.

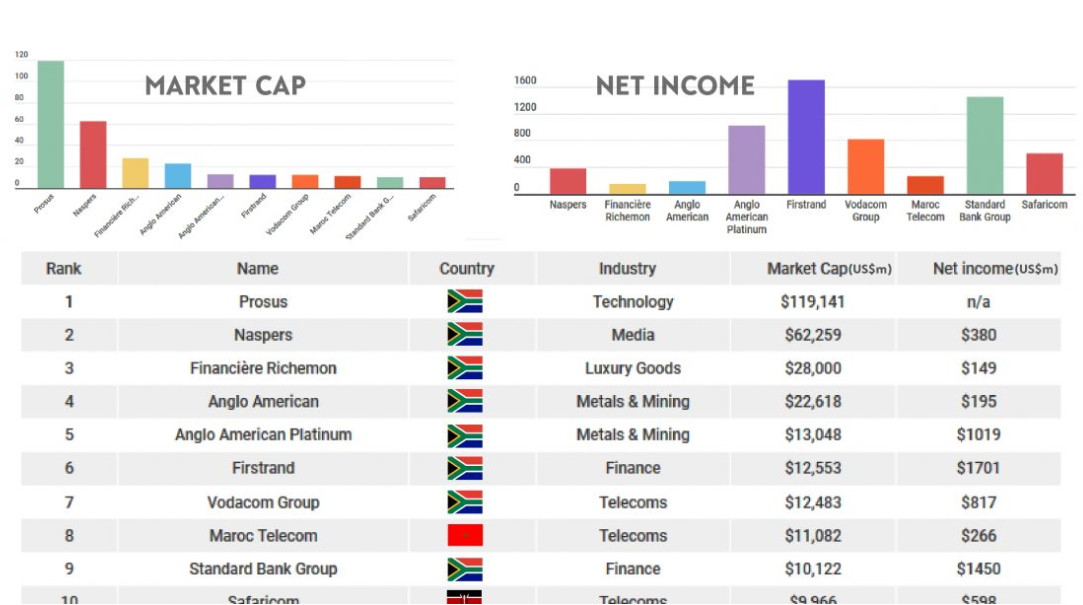

According to the World Bank, the total market capitalisation of the 29 stock exchanges in SSA reached US$1.1 trillion in 2022, representing 60% of the continent’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is a significant increase from the measly US$367 billion in 2010, reflecting the rapid growth and expansion of the equity markets in the region!

Special mention though needs to be made that the distribution of this market capitalisation is highly skewed, with South Africa accounting for 78% of the total, followed by Nigeria with 9%, and Egypt with 5%.

The remaining 26 countries have a combined share of less than 8%, indicating the low level of market depth and liquidity in their jurisdictions. So Africa’s capital market success is not spread evenly across its countries.

South Africa alone has the largest and most developed market, with a total outstanding debt of US$240 billion in 2022, equivalent to 63% of African bond market. As for the other countries, they not only have much smaller and less developed bond markets, but their bond markets are mostly denominated in local currencies, which is not as attractive to foreign players, who constitute the large potion of actors in these markets.

South Africa dominates the market capitalisation of these rankings, partly because it was for many years Africa’s top economy and partly because many leading South African firms have spread worldwide and grown their market capitalisations through overseas primary listings.

This sharp contrast in fortunes between the top three economies of Africa and “the rest” is equally reflected in other economic metrics like economic activities, which has seen a surge in fiscal deficits and public debt, a deterioration in external balances, and a rise in poverty and inequality for the unfortunate “other” countries.

According to the World Bank, the region’s GDP contracted by 2% in 2021, the worst performance on record (perhaps Covid-19 pandemic played a part in this, in all fairness) and then recovered by only 2.7% in 2022, below the global average of 5.6%. The fiscal deficit widened to 5.5% of GDP in 2021, and the public debt increased to 58% of GDP, with 17 countries in that “other” category at high risk or in debt distress.

Over and above the realities of poor distribution of the spoors of success by the capital markets across Africa, there is also the disconnect between the performance of the capital markets themselves and the real economies. This raises the question of whether the capital markets are fulfilling their intended functions of supporting economic development and social welfare, or they now exist as their own economy with no tangible transfer of success or value to other sectors.

A closer look at the structure and dynamics of the capital markets reveals some of the factors that explain this disconnect.

One of these is the low level of financial inclusion and access to capital markets by the majority of the population and businesses in the region.

/

Again, According to the World Bank, only 43% of the adults in SSA have an account at a financial institution or a mobile money service, compared to the global average of 69%. Only 16% of the adults have access to formal credit, compared to the global average of 33%. Only 18% of the adults have access to formal savings, compared to the global average of 36%.

The situation is even worse for the poor, women, rural residents, and informal sector workers, who face multiple barriers to access financial services and products, as these World Bank figures are only averages.

Similarly, only a small fraction of the businesses in the region have access to capital markets, especially the small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which account for 90% of the businesses and 80% of the employment in the region. The SMEs face high costs and risks of accessing capital markets, due to the lack of information, collateral, credit ratings, and legal protection.

As a result, the capital markets are largely dominated by a few large corporations, mostly in the extractive, financial, and telecommunication sectors, which have the resources and connections to tap into the markets.

Exciting news that we hear from the corridors of power suggest a few SSA countries are at various stages of implementing SME centric capital markets like SME Banks and SME stock Exchanges with one due to be officially opened within a few weeks (and we will break the news here). All these bode well for the real economies and, if implemented properly, will narrow the success gap currently existing between the capital markets and the real economies in Africa.

Another factor explaining the disconnect between capital markets success and the real economies in Africa is the high level of volatility and uncertainty in the capital markets, which undermines their stability and efficiency of real economies while capital markets actual thrive on this volatility.

African real economies are commodity driven, therefore exposed to various sources of shocks, such as commodity price fluctuations, exchange rate movements, political and social unrest, natural disasters, and pandemics.

These shocks can, and often do, trigger sudden and large swings in the prices and returns of the commodities, as well as capital flows in and out of the country current accounts. For instance, in 2015, the collapse of the oil prices and the depreciation of the local currencies led to a sharp decline in value inflows into Nigeria and Angola, two of the largest oil exporters in the region, explaining both the economic and political turmoil that ensued in these respective countries thereafter.

Such episodes of volatility and uncertainty create challenges for the real economies leaving “smart money” (investors, issuers, and regulators of the capital markets) to redirect “value” to capital markets and away from the real economy, to cope with the changing market conditions and mitigate risks.

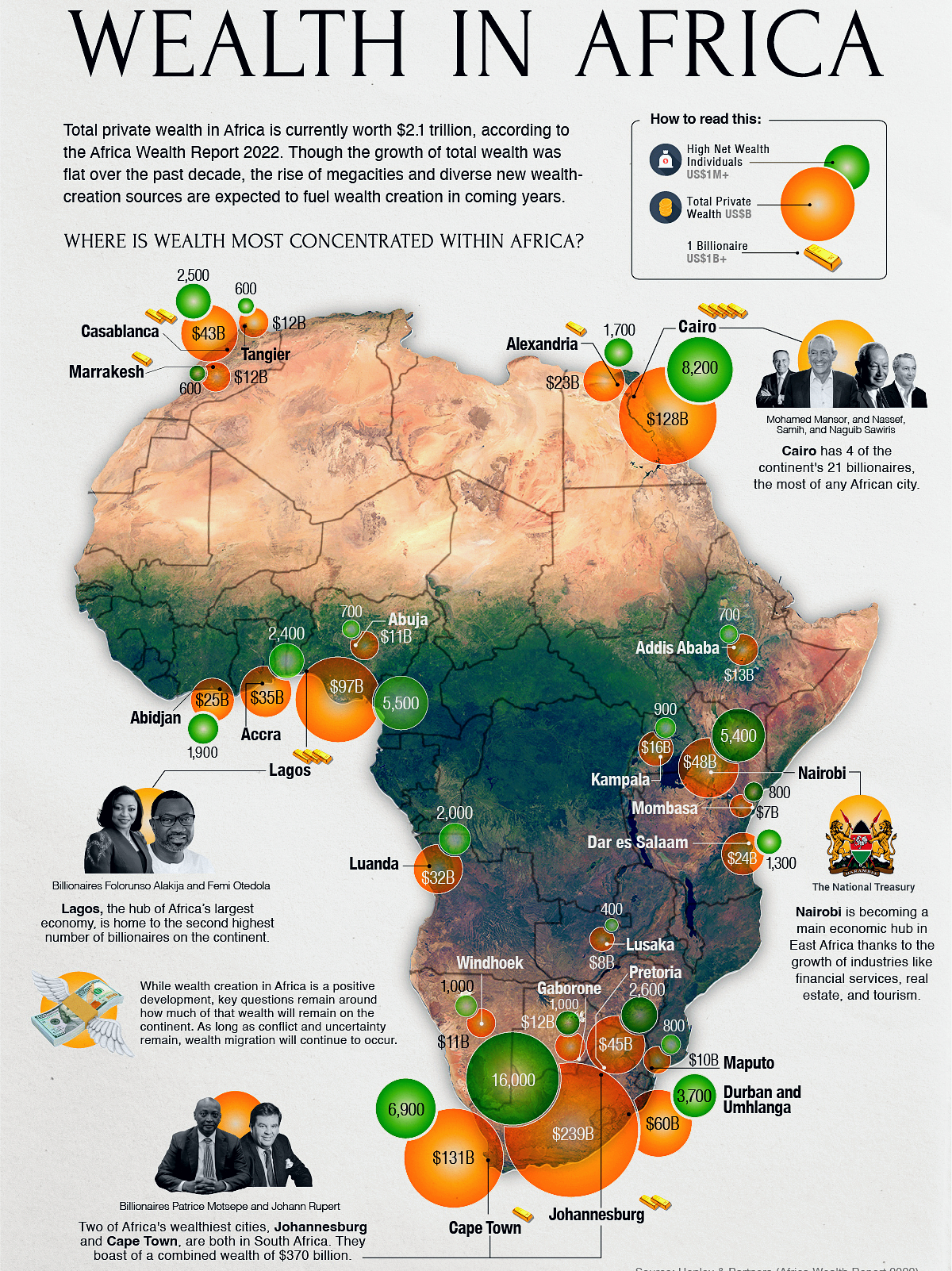

Where wealth is concentrated within Africa.

A third factor, arguably, is the weak governance and regulation of the capital markets, which affects their transparency and accountability. The capital markets in SSA suffer from various governance and regulatory issues, such as the lack (or loose enforcement) of disclosure and reporting standards, the prevalence of insider trading and market manipulation, the absence of effective oversight and enforcement mechanisms, and the vulnerability to corruption and fraud.

These issues erode the trust and confidence of the market participants, and reduce the quality and reliability of the market information and signals.

For example, in 2016, the Securities and Exchange Commission of Nigeria (SEC) suspended the director-general of the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE) for alleged financial mismanagement and abuse of office. In 2018, the Capital Markets Authority of Kenya (CMA) fined two stockbrokers for engaging in irregular trading activities and violating the market rules.

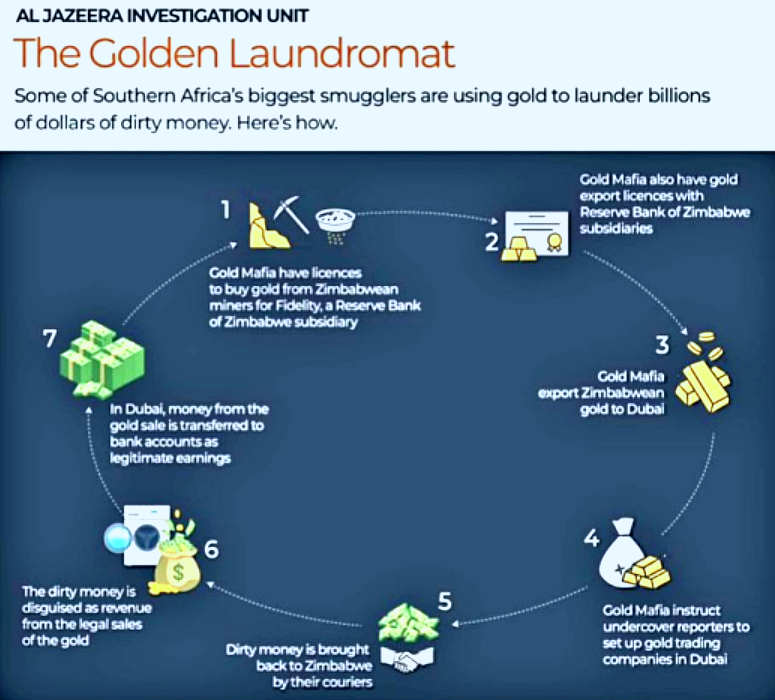

Recently, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) faced sanctions following allegations that it was being used for money laundering and illicit gold dealings. The bank’s governor, Dr. John Mangudya, denied the allegations, which were in a four-part Al Jazeera investigative documentary. The documentary detailed how a criminal syndicate allegedly linked to high offices in the country, was laundering money and smuggling gold from Zimbabwe to Dubai.

Allegations by Al Jazeera investigative unit on how a racketeering group laundered money through gold.

These examples, on the least, cast very long shadows on the strength and enforceability of legal and regulatory frameworks of capital markets in sub-Saharan Africa. At worst they show these markets as still weak and vulnerable to corruption, fraud, and manipulation. These practices not only undermine the integrity and efficiency of capital markets, but also erode the trust and confidence of investors and the public.

They also divert resources from productive sectors and deprive the region of much-needed revenues and development opportunities. Therefore, there is a need for more transparency, accountability, and enforcement of capital market rules and regulations in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as more cooperation and coordination among the relevant authorities and stakeholders.

An overall assessment will thus be that performance of capital markets in sub-Saharan Africa benefits a few countries while for the rest it raises questions about their impact on the region’s economic and social development. For the few making a meal out of it they have reported impressive profits and returns, the benefits yet still even in these three or four countries, benefits have not trickled down to the real economy, and by extention, to the majority of the population, who are vulnerable to poverty, inequality, and exclusion.

For instance, the banking sector in Zimbabwe has recorded sky-high profits in recent years, but the country’s economy has been plagued by hyperinflation, currency crisis, and low growth. Similarly, the insurance sector in the country has been accused of failing to protect the value of policyholders and pensioners, who lost their savings due to the devaluation of the local currency. This prompted the government to issue Statutory Instrument 162 of 2023, which compels insurers to refund contributors who incurred losses through inflation. An example of where regulatory frameworks can be strengthened to protect the real economy and instil confidence.

Capital markets can play a key role in mobilising and allocating resources for these sectors, as well as promoting environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards and practices. However, the evidence of such alignment is still limited and uneven across the region. For instance, while some countries, such as Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, have issued green bonds to finance climate-friendly projects, others, such as Angola, Ghana, and Zambia, have accumulated unsustainable external debt that hampers their fiscal space and development prospects.

In conclusion, capital markets in sub-Saharan Africa have shown some progress and potential, but their successes is still being realised in a few specific cases and not evenly spread across board. In those countries too where they are a success it seems they are such only for the specific sector with questionable transfer of such successes to the real economies which largely remain susceptible to external shocks, like commodity prices.

There is a need for more reforms and innovations that can deepen and diversify capital markets, improve their access and affordability, bridge the gap between supply and demand of capital, and align them with the region’s development goals and needs.

As for Equity Axis Media, a leading financial media and research firm, it is committed to providing financial insights at your fingertips and to fostering informed and inclusive dialogue on the role and performance of capital markets in sub-Saharan Africa. We invite our readers and stakeholders to join the media to celebrate on the occasion of its 100th issue edition.

Happy investing!