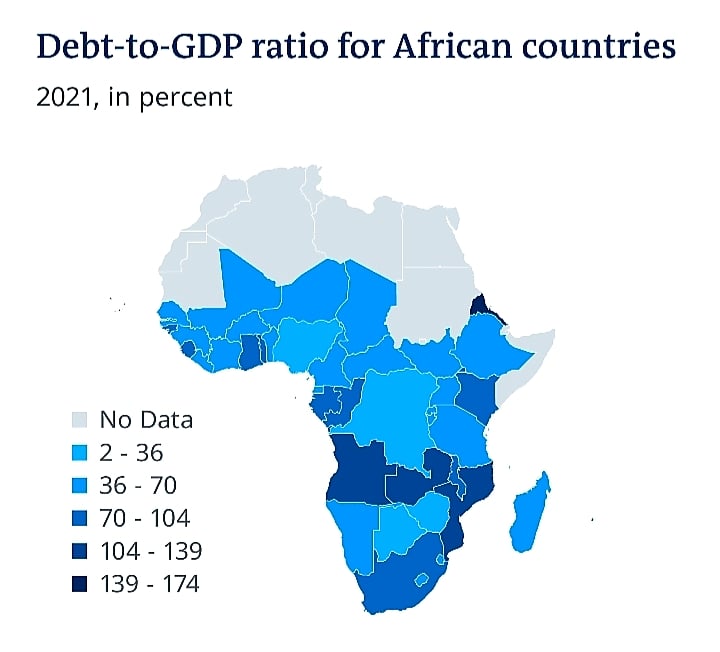

Africa is facing a severe debt crisis that threatens to derail its economic and social progress. According to the IMF, more than half of all low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa are already in or at high risk of debt distress.

The geo political issues post Covid-19 pandemic, like Russo-Ukraine war or the middle east friction, have exacerbated the situation for the affected countries, as revenues have plummeted and spending needs have soared to match. Many African countries are struggling to service their debts, and some have already defaulted or sought relief.

In this context, African leaders have been quick to point fingers at the credit rating agencies, accusing them of being biased, unfair, and insensitive to the continent's challenges. They claim that the agencies do not appreciate Africa's strengths and potential, and that they apply harsher standards and criteria to African sovereigns than to their peers elsewhere.

They argue that the rating agencies' downgrades have made it harder and more expensive for African countries to access the much needed international capital markets, and have equally undermined their efforts to mobilise domestic and foreign resources for development.

But is this criticism justified? Are the rating agencies really the villains of Africa's debt story? Or are they simply doing their job of assessing and communicating the relative risk of default? And more importantly, is blaming the rating agencies the right strategy to address Africa's debt woes? Or is it a distraction from the real and urgent solutions that are needed?

Here we will examine these questions and explore if African criticism of credit rating agencies is misguided and counterproductive. We will also discuss what African countries and their creditors must do to resolve the debt crisis and unlock the continent's potential for sustainable and inclusive growth.

What do the rating agencies do?

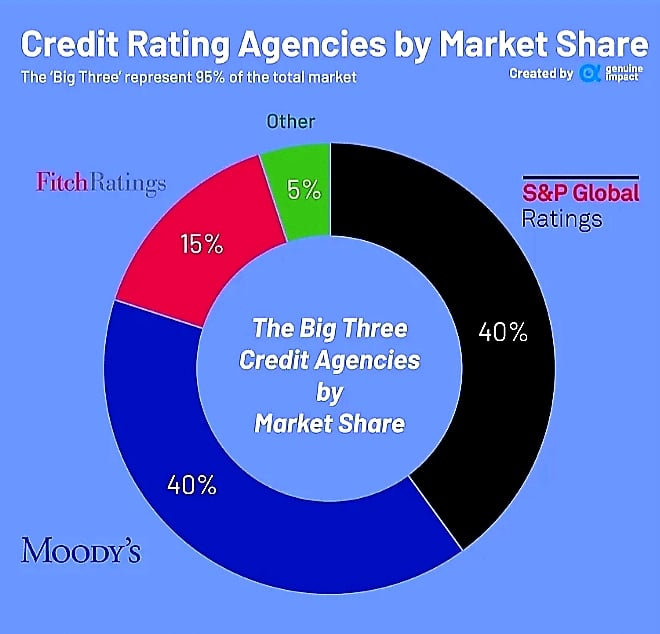

Credit rating agencies are private firms that provide opinions on the creditworthiness of debt issuers, such as sovereigns, corporations, and financial institutions. They assign ratings that reflect their assessment of the likelihood and severity of default, based on a range of factors, such as economic performance, fiscal and monetary policy, institutional quality, political stability, external vulnerability, and debt sustainability.

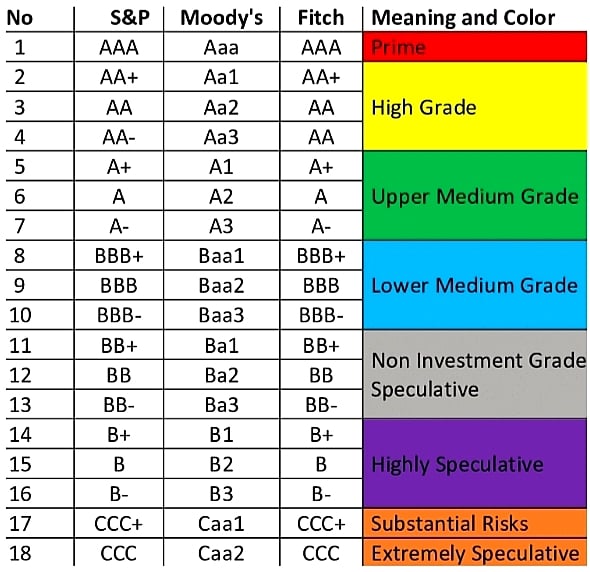

Credit ratings range from AAA (highest) to D (lowest), with different variations and symbols, depending on the agency. Generally, credit ratings can be divided into two categories: investment grade and speculative grade. Investment grade ratings indicate that the issuer or security has a low risk of default and is suitable for conservative investors. Speculative grade ratings indicate that the issuer or security has a high risk of default and is suitable for risk-seeking investors.

The rating agencies' main clients are investors, who use their ratings as a guide to allocate their funds and price their risks. The ratings also influence the borrowing costs and market access of the debt issuers, as higher ratings imply lower interest rates and wider investor base, and vice versa.

Their methodologies and criteria are publicly available and apply to all debt issuers, regardless of their geography or culture and they also monitor and update their ratings regularly. Taking into account new information and developments that may affect the creditworthiness of the debt issuers.

Is there a bias against Africa?

That is the question.

African leaders have often complained that the rating agencies are biased against Africa, and that they do not recognise the continent's achievements and prospects. They argue that these agencies are too pessimistic and conservative in their analysis, and that they ignore the positive factors and opportunities that Africa offers, such as its young and dynamic population, its rich natural resources, its growing middle class, its innovation and entrepreneurship, and its regional integration and cooperation.

They also claim that they are too influenced by the views and interests of their Western and developed country clients, and that they do not understand or appreciate the African context and realities. This suggests that the the agencies apply a double standard and a one-size-fits-all approach to Africa, and that they are not taking into account the diversity and heterogeneity of the continent and its countries.

But are these claims true? Is there any evidence of a systematic and deliberate bias against Africa by the rating agencies? And if so, what are the consequences and implications of such a bias?

To answer these questions, we need to look at the data and the facts. Numbers do not lie after all. We need to compare the ratings and the default rates of African sovereigns with those of their peers elsewhere, and see if there is any discrepancy or inconsistency. This will culminate in us examining the rationale and the reasoning behind the rating agencies' decisions and actions, and see if they are based on sound and objective analysis or on subjective and arbitrary opinions.

What does the data say?

The data shows that there is no anti-African bias in the rating agencies' assessments and ratings. On the contrary, the data shows that the rating agencies perhaps have been more lenient and generous to African sovereigns than to their peers elsewhere, and that they have overestimated rather than underestimated their creditworthiness.

According to S&P Global, the average rating for sub-Saharan African sovereigns as of December 2023 was B-, which is six notches below the global average of BBB. However, the average default rate for sub-Saharan African sovereigns rated in the B category between 2010 and 2023 was 22 per cent, which is higher than the global average of 16 per cent for the same rating category. This means that African sovereigns rated in the B category were more likely to default in their debt servicing than their peers elsewhere within the same rating.

Similarly, according to Moody's, a leading rating agency, the average rating for sub-Saharan African sovereigns as of December 2023 was B2, which is five notches below the global average of Baa2. But just as S&P Global data clearly demonstrates, the average default rate for sub-Saharan African sovereigns rated in the B category between 2010 and 2023 was 30 per cent, which is higher than the global average of 15 per cent for the same rating category by the agency! This directly implies that African sovereigns rated in the B category were twice as likely to default than their peers elsewhere with the same rating!

Thus these figures irrefutably indicate that rating agencies have been more optimistic and favorable to African sovereigns than to they have been with peers elsewhere, and that they have given them higher ratings than they deserved, based on their actual performance (or lack thereof) and risk. So, if anything, the rating agencies have been more than generous to Africa giving favourable classifications as implied by higher default rates that ensure. Simply put, if rating agencies went strictly by the default rate then African countries would be rated even lower than they currently are.

Why then have the rating agencies been more lenient to Africa?

One possible explanation for the rating agencies' more lenient approach to Africa is that they have taken into account the positive factors and opportunities that Africa offers, as well as the challenges and constraints that it faces.

They may have recognised that Africa is not a homogeneous or monolithic entity, but a diverse and heterogeneous continent with different countries, cultures, and contexts. Acknowledging that Africa is undergoing a process of transformation and development, and that it has, by many measures, made significant progress and achievements in various areas, such as poverty reduction, human development, governance, democracy, peace and security, and regional integration.

Another possible explanation is that the agencies have been influenced by the views and interests of their African and emerging market clients, who have been more active and prominent in the international capital markets in recent years. So they realise that being too punitive to Africa is swimming against the tide as economic players are showing an appetite to fund Africa, regardless.

They may also be acting in response to the feedback and pressure from the African governments and institutions themselves, who have been more vocal and assertive in their interactions and engagements with the rating agencies, therefore mindful of the potential impact and implications of their ratings and actions on the African economies and societies, and on the global stability and prosperity.

What are the consequences and implications of the rating agencies' more lenient approach to Africa then?

On the positive side, the rating agencies’ more lenient approach may have helped African countries to access the international capital markets and diversify their sources of financing. It may have also encouraged African countries to improve their macroeconomic management and policy frameworks, as well as their transparency and accountability, in order to maintain or enhance their ratings.

Not to be underestimated also is the boosting of confidence and optimism of the African governments and people, as well as the international community, on the continent’s prospects and potential through these ratings leading to more proactive and beneficial policies.

On the negative side, this lenient approach may have contributed to the accumulation of excessive and unsustainable debt by some African countries, who likely borrowed more than they could afford or repay. As is evident in many Sub Sahara governments, this created a false sense of security and complacency among some of them as well as their creditors, who may have underestimated or ignored the risks and vulnerabilities of the debt situation.

This in turn has delayed or discouraged the implementation of necessary structural reforms and adjustments by some African countries, who may have relied too much on external financing and avoided making difficult choices and trade-offs.

What is the solution to Africa’s debt crisis?

The solution to Africa’s debt crisis is not to blame or boycott the rating agencies, but to address the root causes and the underlying issues of the debt problem. The solution is to pursue a comprehensive and coordinated approach that involves all the relevant stakeholders, such as the African governments, the creditors, the rating agencies, and the multilateral institutions.

There is an urgent need to implement faster and more effective debt restructuring mechanisms that can provide adequate and timely relief to the distressed African countries, and restore their debt sustainability and fresh market access. The solution must include adopting sound and prudent fiscal and monetary policies that will enhance the credibility and resilience of the African economies, whilr reducing their dependence and vulnerability to external shocks.

Equally significant is to pursue structural reforms and investments that can boost the productivity and competitiveness of the African sectors and industries, and diversify sources of growth and revenue for these countries, particularly revamping their economies from the Primary (extractive) Industry. There must be deliberate plans to leverage the opportunities and innovations that the green and digital transitions offer, and tap into the potential of green bonds and digital currencies to mobilise and allocate resources for sustainable development.

Finally, there must be a concerted effort to resolve the debt crisis itself, as opposed to miring the countries into more debt. This will give rise to more opportunities to transform and modernise the African economies and societies. Opportunities to unleash and harness the human and natural capital of the continent. Opportunities to create and share prosperity and well-being for all.

The solution therefore, is to act now, before it is too late, act together, as partners and stakeholders, act boldly, with vision and ambition, while doing less of finger pointing. Business is business.