The Zimbabwe Ministry of Finance, Development and Investment Promotion has announced it is consolidating 11 different local authority licences into a single unitary business licence with a total price cap of US$500.00 to increase the ease of doing business.

The streamlined fee structure is designed to lower barriers to entry, incentivise the transition of informal enterprises into the formal economy, and free up working capital for productive investment, expansion, and employment generation.

This reform follows sustained advocacy from industry and commerce bodies, which highlighted the prohibitive burden of navigating numerous, costly, and often overlapping licensing requirements as a major impediment to lawful business operation.

This seems to coincide with a renewed government impetus to formalise SMEs in this policy pivot.

This initiative thus represents a significant, and commendable, step by the authorities towards dismantling the bureaucratic thicket that has long choked SME dynamism in Zimbabwe. The political will to consolidate fragmented licensing, cap arbitrary municipal fees, and, importantly, align administrative processes with regional benchmarks is both timely and necessary.

The analysis herein, rooted strictly on the five published Schedules (attached with this text), is offered not to undermine or even vilify this progress, but as a stress-test of the framework’s internal coherence, integrity, and capacity to deliver on its Vision 2030-aligned promise.

This then ensures the well-intentioned policy translates into efficient, unambiguous execution.

THE “SINGLE LICENSE” PROMISE UNDERMINED BY RESIDUAL FRAGMENTATION

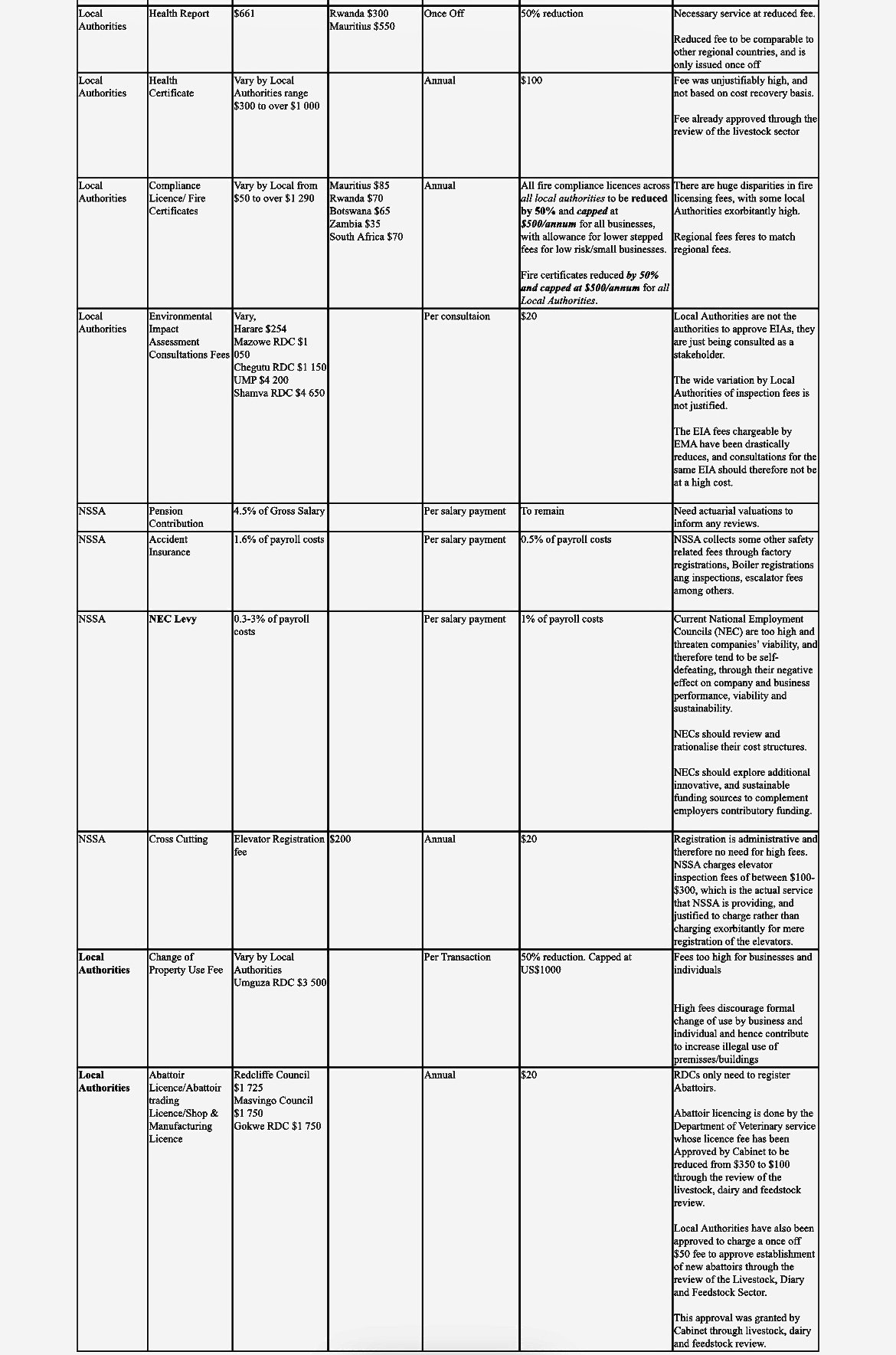

SCHEDULE 1: Of The Zimbabwe Licences, Permits, Levies And Fees For The Wholesale Sub Sector & The Proposed Reviewed Fees

The reform’s headline achievement is its replacement of 11 licences with one unitary Shop Licence capped at US$500.00, which is all conceptually sound. Yet Schedules 1 and 5, of the five that accompanied the announcement, reveal some design quakes.

While the Shop Licence is presented as “all-encompassing,” separate “registration fees” of US$20 each persist for Liquor and Financial Services activities (as Schedule 1 above shows).

For instance, a typical SME operating as a supermarket, mobile money agent, and bottle store, which is quite common in Zimbabwe’s retail landscape, this implies that such a business will pay mandatory payments beyond the US$500 ceiling, unless future pronouncements explicitly state these are to be absorbed in the main fee.

Absent such clarification, the reform’s application will, in practice, introduce “re-fragmentation by stealth.” So businesses engaging in multiple regulated activities will face de-facto tiered pricing, violating the principle of a single, predictable entry cost.

To preserve the integrity of the “one licence” model, all ancillary registrations must either be explicitly included within the US$500 cap OR abolished altogether. Ambiguity here will breed compliance confusion and erode trust in the reform’s simplification promise.

BENCHMARKING IGNORES TRUE COST OF COMPLIANCE

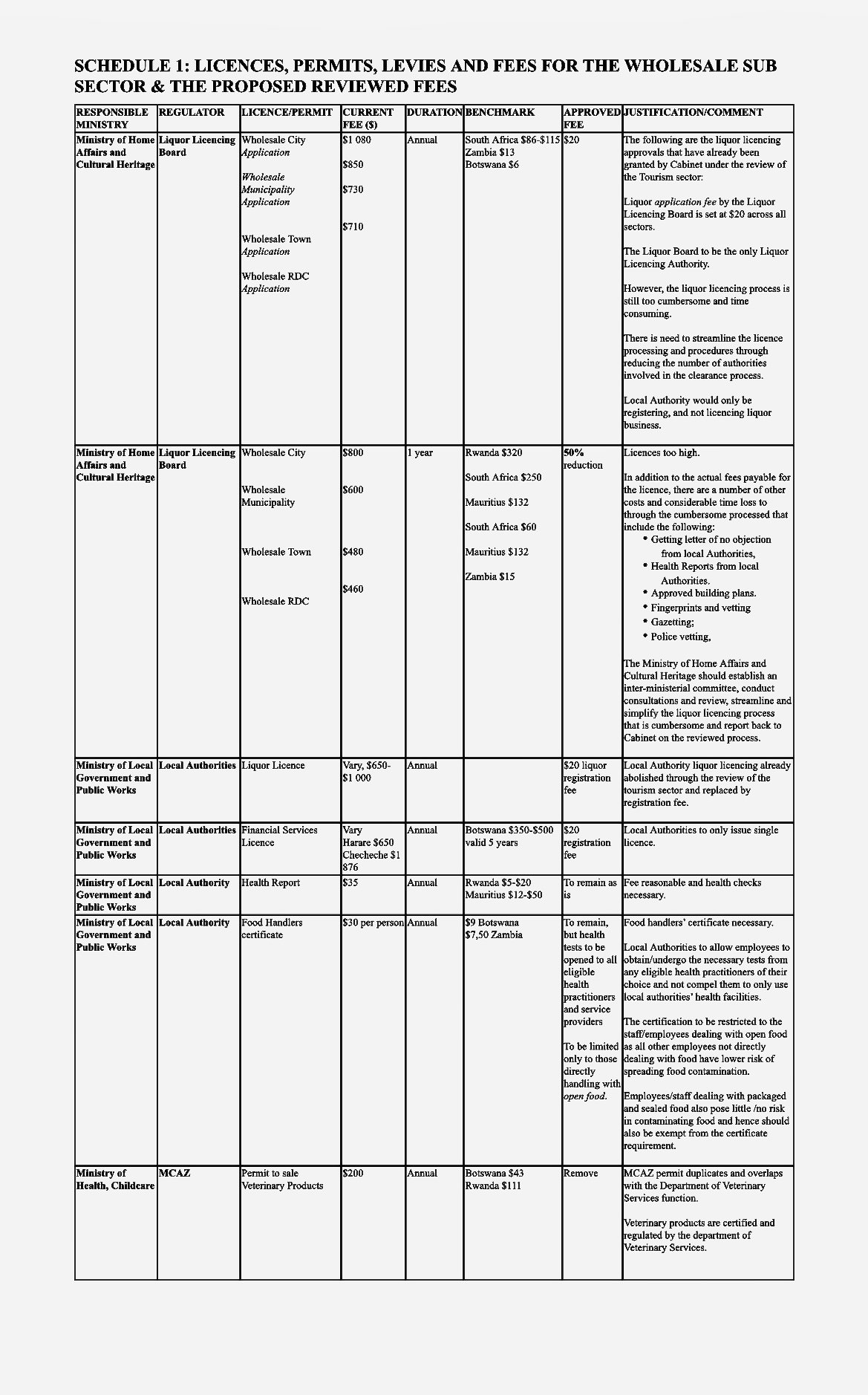

SCHEDULE 2 Of The Zimbabwe Licences, Permits, Levies And Fees For The Wholesale Sub Sector & The Proposed Reviewed Fees

The US$500 cap is justified by the Ministry through comparisons to Rwanda ($50.00), Botswana ($111.00), and Mauritius’ ($250.00) licensing fees. But this benchmarking is incomplete. It seems to measure only the monetary fee of licensing and not the total compliance cost.

If that’s the case, it is an oversight in a Zimbabwean context where procedural friction is the primary barrier to formalisation.

As noted in Schedule 1 above, even after paying the fee, an SME must still secure:

- A letter of no objection from Local Authorities

- Health reports

- Approved building plans

- Police vetting and fingerprinting

- Environmental Management Agency Clearance

- Gazette publication, etc

These are “non-fee” costs where time is lost, wages paid for idle staff perchance, transport expenses incurred, and opportunity costs from delayed market entry. In the said Rwanda case, their entire process is digital and is completed in under 24 hours.

In Zimbabwe, by contrast, it can take weeks. So consolidating and capping the fee and then leaving procedural burdens unaddressed omits to tackle the core pain point for SME compliance, which is regulatory uncertainty.

For the reform to truly “ease” doing business, it must standardise, and time-bind approval workflows, not just shrink the fee invoice.

THE UNSPOKEN, JUST AS POWERFUL AS THE SPOKEN

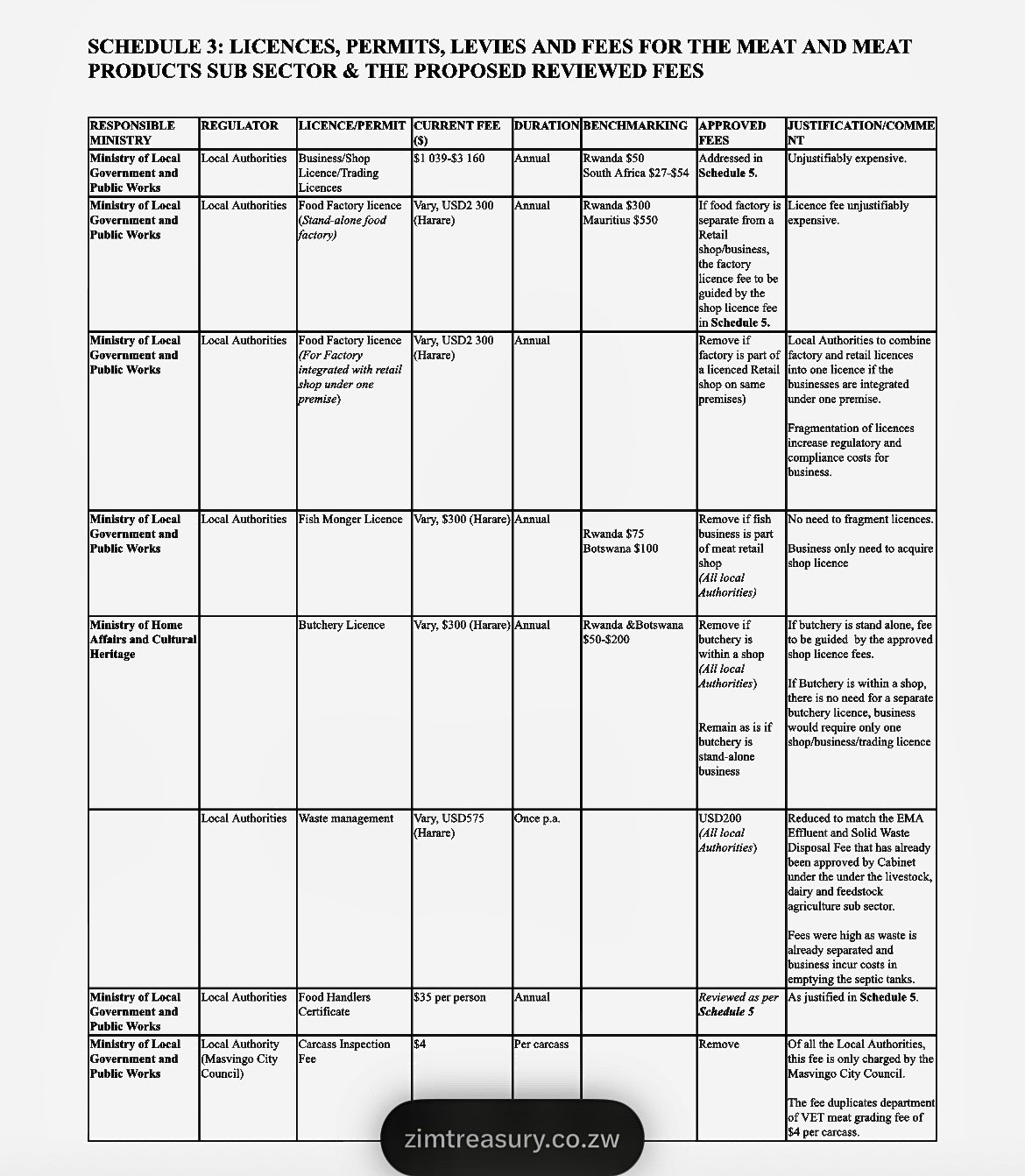

SCHEDULE 3: Of The Zimbabwe Licences, Permits, Levies And Fees For The Wholesale Sub Sector & The Proposed Reviewed Fees

Perhaps the most consequential, yet unspoken, effect of the reform is a the structural transfer of fiscal authority from Local Authorities (LAs) and sectoral agencies to the central government, via the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA).

In simple terms, by collapsing the 11 local and sector-specific fees businesses pay to LAs, averaging US$3,224.00 per SME annually, into a single US$500.00 licence, the reform eliminates a critical cash cow from the revenue matrix of LAs, while leaving national tax obligations untouched.

This has a net effect of corralling informal (albeit some unregistered) businesses into the tax net, with the lure of lower barriers to entry. Their licensing inadvertently (or intentionally) leads to the businesses formally registering as tax paying entities, where no concessions have been announced.

For the LAs, this will exacerbate their revenue stress position, which may, in turn, motivate them to levy higher rates on basic amenities they provide (like water) to cover the gap.

Based on officially published data, Zimbabwe has 92 Local Authorities which collected US$1.84 billion in total revenue in 2023, of which US$192.4 million (10.5%) was derived from licence and permit fees, including trading licences, health certificates and liquor permits (Ministry of Local Government and Public Works, 2023, “Local Authority Financial Performance Report 2023”, page. 12-15).

While the 2024 consolidated figure remains unpublished, extrapolating from growth trends, the 2025 combined LA revenue may reach US$2.0 billion this year. With licence fees representing a conservative upper-bound 15% of that total (consistent with stakeholder estimates of pre-reform burdens). The implied pre-reform licence revenue, thereof, would be US$300 million from these permits and licence.

Using the average pre-reform SME licence average burden of US$3,224 per SME, from approximately 93,000 formal SMEs that are registered and pay fees, under these new reform, with fees now capped at US$500 per SME, the same cohort would generate only US$46.5 million, representing a US$253.5 million (84.5%) decline in licence revenue, and a 12.7% reduction in total Local Authorities income.

If the Zimbabwe treasury department is hoping the informal and unregistered SMEs will come in to cover the gap, attracted by lower fees, that is nigh on impossible as half a million “new” SMEs will need to register for these streamlined licences, just to replace the US$250 million odd lacuna that’s now created in the LAs’ top line!

All this is going to erode the financial foundation for essential municipal functions, including health inspections, waste management, fire compliance, and business oversight, all of which are mandated, yet unfunded now, under this new fee regime.

Without a compensatory inter-governmental fiscal transfer, or a mechanism to recover costs through user-fees tied to actual service delivery (e.g., risk-based health inspections), Local Authorities will face an impossible choice - under-enforce regulations (increasing public health and safety risks), or, reimpose informal levies (recreating the very red tape the reform seeks to eliminate).

The result is now ease of doing business, with regulatory fragility, where simplification at the centre triggers decentralised dysfunction at the local level. Already before this announcement, the Harare City Council had given notice to hike significantly the water tariff as part of its US$690 million 2026 budget presented in late October 2025.

The council proposed up to 61 percent increases for high-density suburbs and a massive 188 percent for low-density areas “to align charges with the true cost of producing and distributing water.”

The Bulawayo City Council had actually proposed a benevolent budget with no increases whatsoever across all revenue headers. Everyone is now watching what their next announcement will be considering the aforegoing.

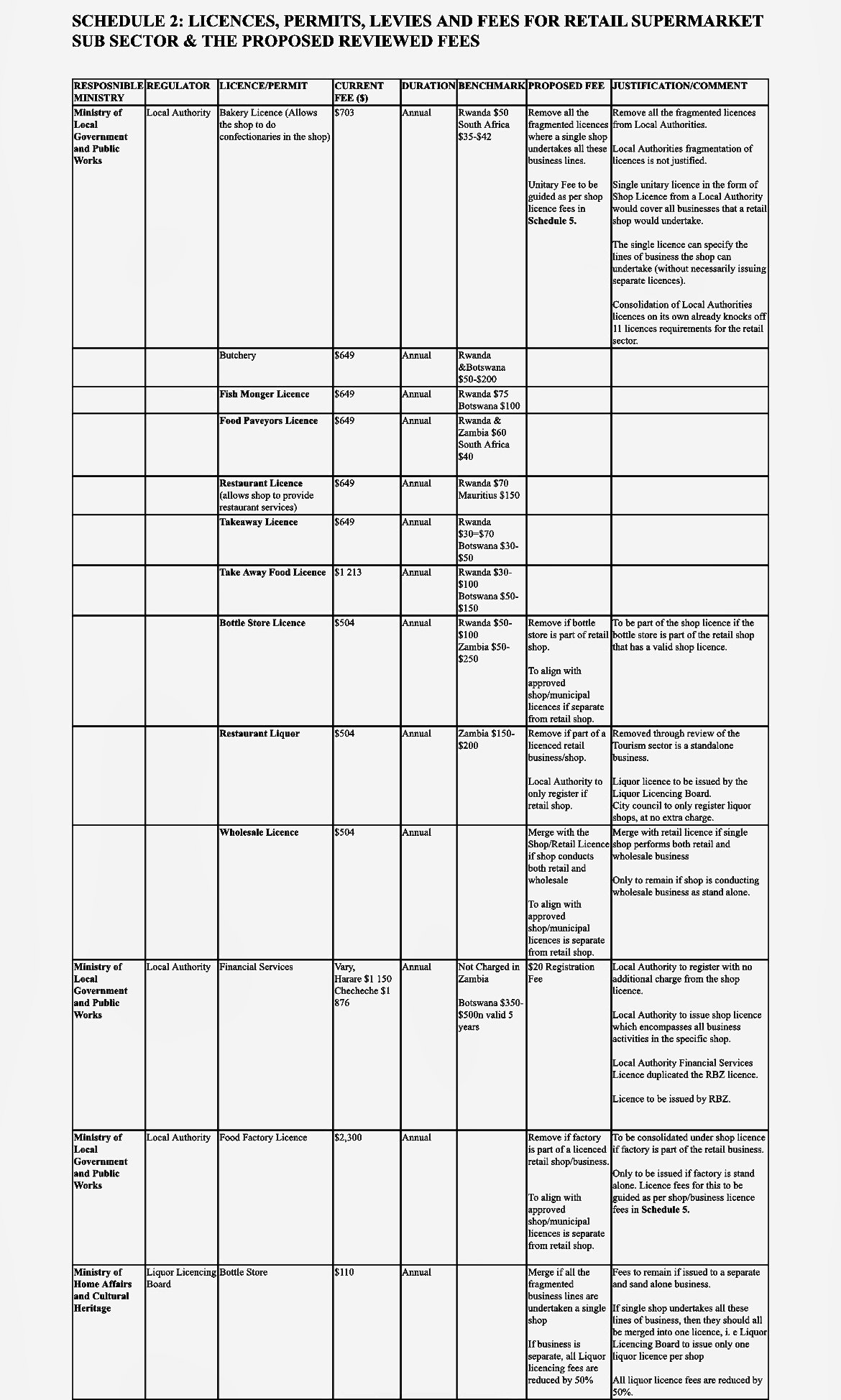

TAXES

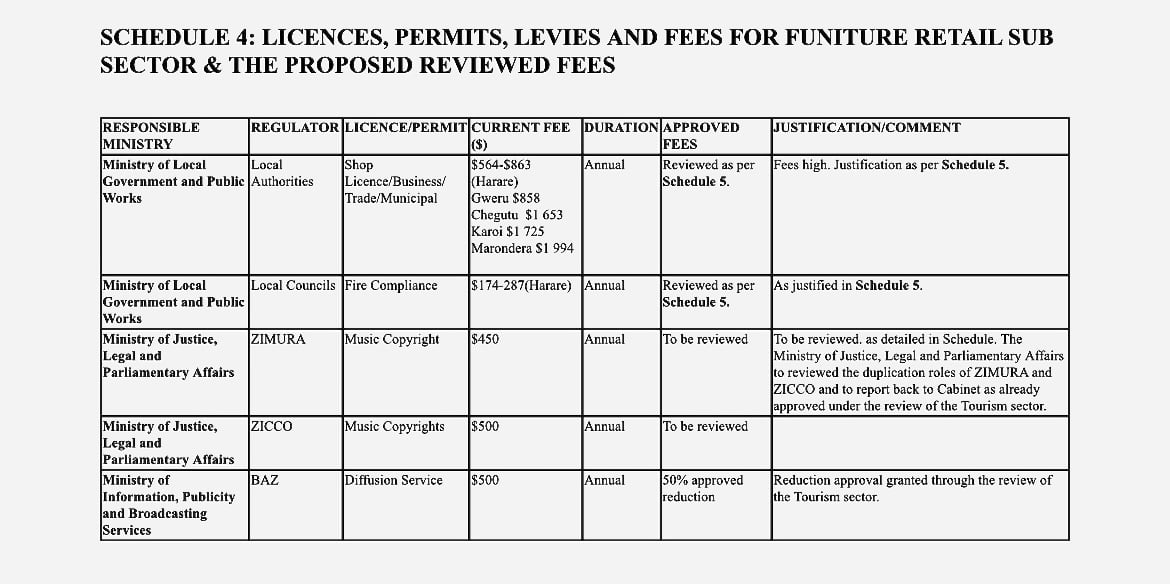

SCHEDULE 4: Of The Zimbabwe Licences, Permits, Levies And Fees For The Wholesale Sub Sector & The Proposed Reviewed Fees

The schedules, interestingly, omit integration with corporate tax. At about 25% of net income, it burdens formalised retailers disproportionately compared to their counterparts that operate on the informal market, and constituting 76% of all sectors (Bloomberg, 2025, Zimbabwe Informal Sector Dominates 76% of Economy, para. 3).

Forensically, this gap ignores how corporation tax may be a bigger inhibitor for smaller SMEs than the compliance licences and permit fees. Could these changes simultaneously be a tool to coral all unregistered businesses to the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA), to increase the tax base, or these will just be unintended consequences, no matter how convenient that’ll be to the fiscus?

This implies the reform is about cost reduction for businesses, but also about their formalisation to tax regime mechanism by offering lower upfront barriers that entice informal traders into the system, after which they become perpetual ZIMRA contributors.

While this may be a deliberate strategy to broaden the tax base (entirely defensible in principle). If that is the case, it should be transparently acknowledged. Otherwise, the “ease” narrative risks feeling like a bait-and-switch, especially when renewal of the US$500 licence inevitably requires a ZIMRA Tax Clearance Certificate (ITF263).

WELCOME CORRECTION TO MULTI-AGENCY DUPLICATION

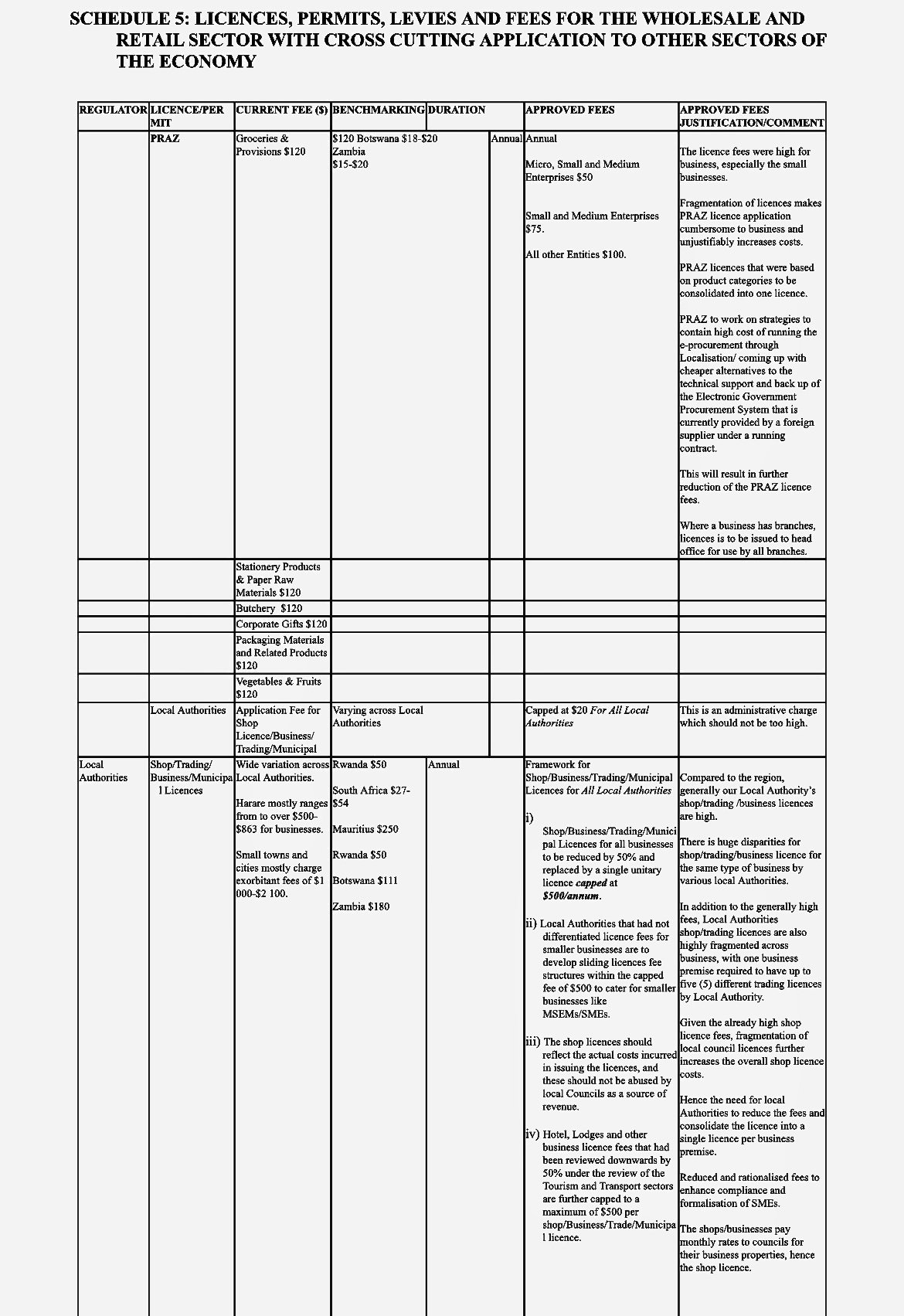

SCHEDULE 5 (PART 1): Of The Zimbabwe Licences, Permits, Levies And Fees For The Wholesale Sub Sector & The Proposed Reviewed Fees

The reform’s commendable outcome, besides price consolidation and capping, is its handling of overlapping mandates and duplications. Schedule 1 rightly abolishes the MCAZ veterinary permit as duplicative of Veterinary Services functions.

Not withstanding Schedule 3, which then retains a standalone “Food Factory Licence” (US$2,300) for meat processors, with unclear linkage to the new Shop Licence, one wonders if this extra fee is to be abolished if the factory is an integrated retail premise? The schedule states it “to be consolidated,” but provides no fee schedule, approval pathway, or effective date.

Such gaps create regulatory grey zones where Local Authorities may continue charging legacy fees under new names. We envisage, before full implementation, abolishment or consolidation of licences. We anlso encourage explicit mapping by authorities, through separate schedules/charts, of a series of prior permits linking to their singular successor (or deletion), in a master crosswalk table.

It is well noted that, and very welcome, that the new fee regime is a welcome correction to years of multi-agency duplication, where SMEs routinely paid overlapping charges to various state and local authority entities. For instance, a Harare-based supermarket previously paid separate fees to the City Council for a shop licence ($863), Procurement Authority of Zimbabwe (PRAZ) for grocery registration ($876), and the Health Department for food handlers’ certificates ($150 per staff member), despite all relating to a single business premise.

Similarly, a meat-processing butchery in Masvingo would navigated a regulatory gauntlet, paying the Ministry of Health for hygiene certification, the Department of Veterinary Services for carcass inspection, the Environmental Management Agency (EMA) for effluent discharge permits, and the City Council for a butchery licence, often for the same sanitary compliance outcome, resulting in triple-layered fees for one operational reality.

By consolidating these into a single $500 Shop Licence that encompasses all on-premise activities, the reform eliminates redundant payments and streamlines approval. This is a critical relief for capital-constrained entrepreneurs, especially SMEs

CONCLUSION

SCHEDULE 5 (PART 2): Of The Zimbabwe Licences, Permits, Levies And Fees For The Wholesale Sub Sector & The Proposed Reviewed Fees

The Treasury’s reforms are directionally correct, and politically courageous. They correctly identify licensing fragmentation as a barrier and propose a bold, cap-based simplification. However the intention seems to go beyond the stated. Not that it diminishes the “good” in the intention, pun intended, but it creates great rapport between the authorities and SMEs if there is honest and open communication between the authorities and entrepreneurs from the outset.

Further to the proposal and the accompanying schedules, business would love to see:

1. Clarify - the scope of the US$500 licence: Explicitly stating whether ancillary registrations (liquor, PRAZ, etc.) are included or abolished.

2. Publication of a time-bound compliance protocol: Defining maximum processing times and digital submission pathways (not manual) to address non-fee frictions/burdens.

3. Release a fiscal impact assessment: Showing how local authorities will be compensated/accomodated for lost revenue to prevent informal re-levying and to capacitive statutory mandate to supervise compliance.

4. Engage ZIMRA: To fill in the knowledge gap through specific outreach programmes that target new businesses that register for the first time so they do not foul tax laws from ignorance.

So all in all, this is not criticism of such a noble gesture to reduce licensing and permit fees for businesses, but it is “constructive reinforcement.” With these refinements, Zimbabwe’s Ease of Doing Business reforms can transition from a pyric victory to a lived reality for its SMEs, local authorities, and the government via its various agencies.

The foundation is laid; now, the precision work begins.