So Zimbabwe has operationalised its Sovereign Wealth Fund, now nostalgically named the Mutapa Fund. The country can, at least on paper, “save and invest.” What may be needed now, assuming that the fund will function as intended, is a formal, government led, initiative to have citizens also conventionally “save and invest” in the country.

Can Zimbabwe leverage its large and diverse diaspora community to raise funds for its development?

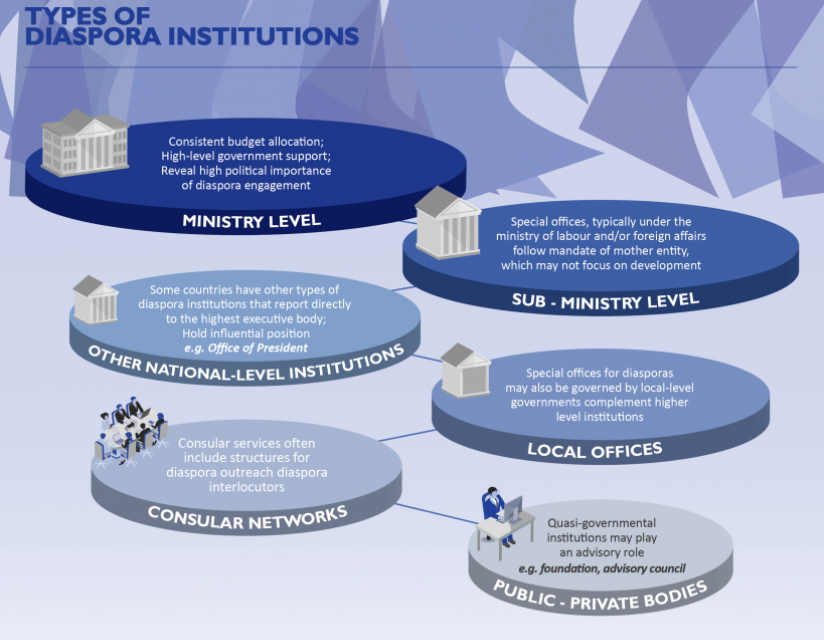

Diaspora community institutions

One such initiative is a Diaspora Bond. These are debt securities issued by a country to its expatriates, who may have a patriotic or sentimental attachment to their home country and be willing to invest in its development. They can, and indeed will, be a source of financing for developing countries, especially in times of crisis or when access to international capital markets is limited, like in the case of Zimbabwe.

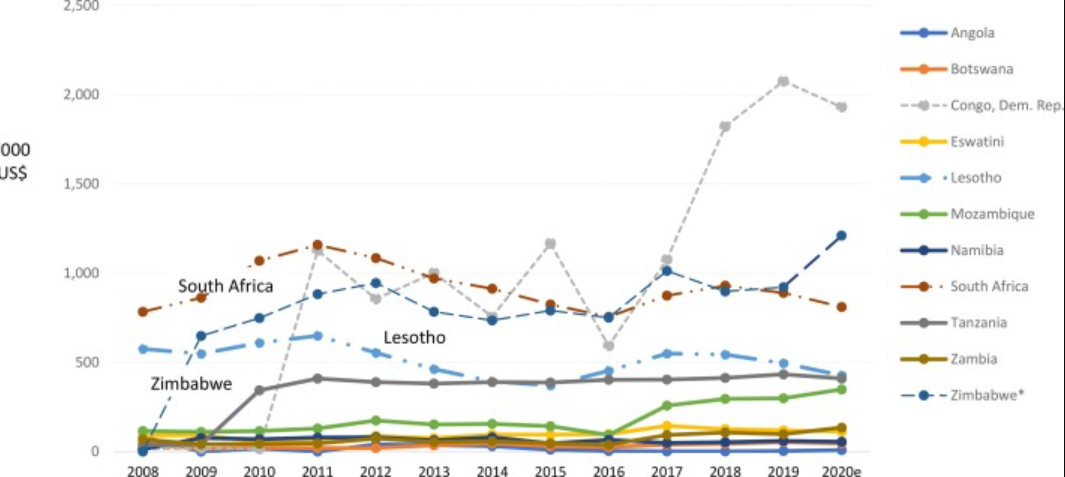

The country has an estimated 3 to 4 million people living abroad, depending on who you ask, and they are mainly in South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States, and other countries. These expatriates send back significant amounts of money to their families and friends in Zimbabwe. Numbers totalled US$1.66 billion last year (2022) – a significant increase from US$1.4 billion in 2021.

This amount is equivalent to about 5% of Zimbabwe’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 12% of its exports thus making remittances now an indispensable source of foreign exchange and income for many households and for the country, by extension through stimulated economic activity, taxation, and the like.

Will Zimbabweans let the country die?

However, these remittances alone are not enough to meet Zimbabwe’s development needs. The country faces many economic challenges, such as, high inflation, fiscal deficit, high debt, and poverty.

According to the World Bank, Zimbabwe’s real GDP growth moderated to 3% in 2022, down from 8.5% in 2021, due largely to exogenous and endogenous shocks. The Zimbabwe dollar depreciated 521% against the US dollar in 2022, triggering an increase in inflation from 60.6% in January 2022 to 285% in June 2022. The fiscal deficit narrowed to 0.9% of GDP in 2022, reflecting fiscal consolidation. Debt stood at $17.5 billion in 2022 (66% of GDP), with external debt estimated at $14 billion and domestic debt at $3.5 billion.

All these numbers signify some distress, though of lower intensity than recorded earlier in the last two decades, poverty and inequality are still unenviably high. The extreme poverty rate alone was an estimated at an astronomical 44% in 2022 in the same World Bank report!

So it goes without saying that the country needs more resources to finance its development agenda and achieve its vision of becoming an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Diaspora Bonds, thus, could be one of the options that Zimbabwe could explore to mobilise additional funds from its expatriates.

This instrument will possibly allow for diversification of the country’s funding sources, while enabling borrowing at below-market rates and on longer tenures, as these bonds could appeal to the altruistic and nostalgic motives of its diaspora rather than purely financial returns.

Politics aside, effective implementation and management of this initiative could also enhance Zimbabwe’s creditworthiness and reputation in international capital markets by demonstrating its ability to service its debt obligations. But then again, politics and economics are inseparable siamese twins so… that is that.

Besides politics, both internal and external, there will be need to overcome several hurdles before this instrument can be successfully deployed to tap into the diaspora community.

Some of these hurdles will include;

the need for an establishment of strong legal and regulatory frameworks that enable issuance and trading of Diaspora Bonds, and ensures transparency and accountability of the use of proceeds.

Unlike the apprehension swirling around the Mutapa Fund, where the laws seem to be aimed at reducing red tape and increasing unencumbered decision making by the board that runs the entity, the Diaspora Bond could need more consultation before any adjustments or implementation to ensure public buy-in. Hence the trepidation and conjecture among some analysts who fear impropriety may ensue in the Sovereign Wealth Fund over its operational life because the public in not being notified beforehand.

Zimbabwe Sovereign Wealth Fund

Another hurdle for the Diaspora Bond is building trust and confidence among the diaspora investors, who may have concerns about the political and economic stability of Zimbabwe, the exchange rate risk, the default risk, and the legal protection of their investments.

Investing, in general, is controlled wholly by the greed vs fear matrix. The more fearful an investor is the less risk taking they will do, with the opposite holding true. So to capture as many investors as possible the Bond must be designed to be an equally attractive and competitive product that offers a reasonable return, a tax incentive, a currency choice, among others, so it appeals to all risk appetites across the “greed vs fear” spectrum.

Equally as important will be the need to Develop a marketing and distribution strategy that can reach a large and diverse pool of potential investors at their bases in their country of residency, using existing networks and platforms that connect the diaspora with Zimbabwe, such as remittance service providers, diaspora associations, online forums, and social media.

This then means the elephant in the room, which reasonably could be the most impactful hurdle before this instrument can be successfully deployed, is managing and cultivating political tolerance, macroeconomic volatility, exchange rate fluctuations, legal disputes, reputational risk, and reinvestment risk.

Be that as it may, there is so much potential for Zimbabwe to make it a great candidate for issuing Diaspora Bonds. Leading among these is the size and generosity of its diaspora community.

According to the World Bank, Zimbabwe ranks among the top 10 remittance-receiving countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, with $1.4 billion in 2021. This amount was equivalent to 4% of Zimbabwe’s GDP and about 10% of its exports.

Moreover, Zimbabwe has one of the highest remittances per capita in the world, at $94 in 2022. This compares favourably, putting it quite higher than other countries that have already issued Diaspora Bonds, such as India ($29), Ethiopia ($28), and Nigeria ($9).

Of paramountcy is that most of the remittances sent to Zimbabwe are used for consumption purposes, such as food, health, education, and housing, rather than for productive investment. Meaning, by extrapolation, citizens, even though they are sending quite a lot per capita, they are also not necessarily sending a large percentage for investment but for consumption, implying that there is still excess capacity which may yet be tapped into.

Zimbabwe ranks high in consumptive remittances but very lowly in investment remittances.

If only the Diaspora Bond could be optioned to technically beat western world investment terms such as exchange traded funds, real estate investment trusts, money market instruments, and microfinance institutions, then Zimbabwe could easily convince its citizens based outside its borders to also consider their homeland even for savings and investments - assuming the hurdles of managing and cultivating political tolerance, macroeconomic volatility, exchange rate fluctuations, legal disputes, reputational risk, and reinvestment risk are corrected or eliminated as needed.

This will ser the country tap into a larger pool of funds from its expatriates who may be willing to invest back home for national development, and not just consumptions.

Zimbabwe can learn from the experiences of other countries that have issued Diaspora Bonds in the past, such as Israel, India, and Ethiopia, alluded to above.

Israel has been the most successful issuer of Diaspora Bonds, raising over $46 billion since 1951 from its global Jewish diaspora. The country used the funds to finance its infrastructure, energy, high-tech, and other projects that contributed to its state-building and economic development.

India, for its part, has also issued several Diaspora Bond-like instruments since 1991, raising over $11 billion from its non-resident Indians. It used the funds to bolster its foreign exchange reserves and cope with its balance of payments crises.

Finally, Ethiopia has issued two Diaspora Bonds since 2008, raising about $40 million from its expatriates. Currently, the round of financing is being deployed to finance a hydroelectric dam and housing projects.

As much as Zimbabwe will need to look at the success stories around the Diaspora Bond, it may want to look with even more scrutiny at countries that have been unsuccessful in issuing Diaspora Bonds, so as to pick valuable lessons.

For instance, Greece failed to raise $3 billion from its diaspora in 2011 amid its sovereign debt crisis. Kenya postponed its plan to issue a $50 million Diaspora Bond in 2014 due to regulatory issues and low demand. Nigeria launched a $300 million Diaspora Bond in 2017 but but failed its targets due to high interest rates and low ratings - the topic of rating houses will deserve its own dedicated article and watch out for that in the coming weeks.

So… what does this mean for Zimbabwe? It means that Zimbabwe has a potential opportunity to issue Diaspora Bonds as a new source of financing for its development.

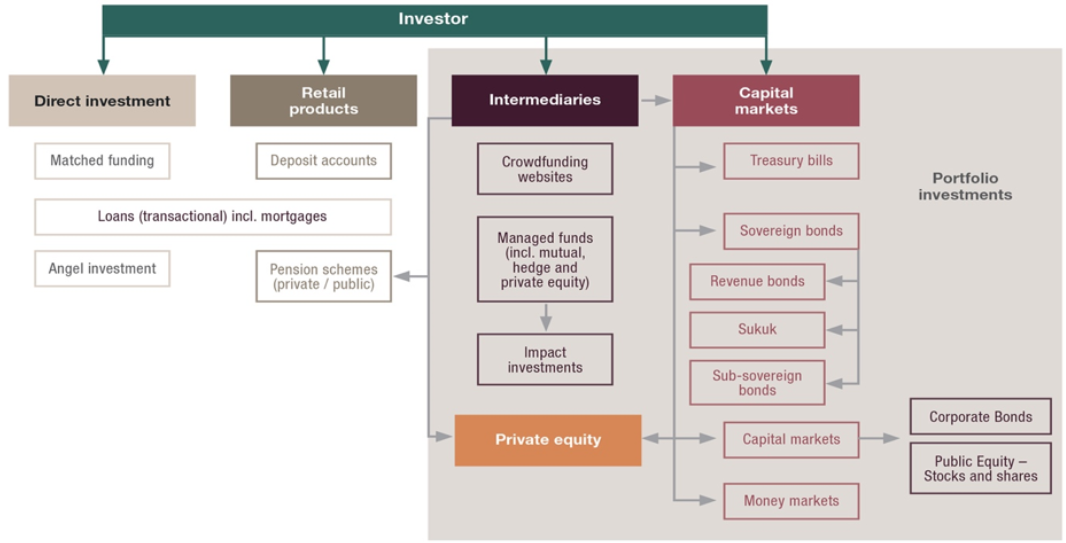

Overview of different investment channels.

Invariably, it also means that Zimbabwe has to carefully consider the benefits and challenges of issuing Diaspora Bonds, and learn from the best practices and lessons of other countries that have done so through to addressing the legal, regulatory, institutional, technical, financial, and social aspects of issuing Diaspora Bonds before it can successfully tap into its diaspora community.

The country’s large and diverse diaspora which is already pliable as they are now used to remitting home anyway could be introduced to this new product if it is shown that it is beneficial for the individuals long term, than just consumptive spending. This will convert this constituency into an indispensable partner in its development journey.

Diaspora Bonds could be a win-win proposition for both Zimbabwe and its expatriates, in that regard. Zimbabwe has the potential to raise funds for its development projects at favourable terms while offering its expatriates an opportunity to invest in their home country’s future. Which will have the instrument work complementary to the Mutapa Fund.

At a social level Diaspora Bonds have the potential to strengthen the ties between Zimbabwe and its diaspora community by fostering a sense of belonging and ownership. A togetherness, not an “us vs them” undertone which is currently bubbling under.

Will Zimbabwe seize this opportunity? Will Zimbabwe issue Diaspora Bonds as a new frontier for its development? Will Zimbabwe’s expatriates respond positively to this initiative? These are some of the questions that Zimbabwe has to answer as it explores this innovative source of financing.