Recently I was scouring Twitter, or X as it is now known, and I stumbled on a thread by Prisca Mutema, a Zimbabwean economist and entrepreneur, which sparked a heated debate on the role and value of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the country’s economy.

Mutema argued that the use of the term SME, in the Zimbabwean context, is a scam that perpetuates a dependency syndrome among business owners and hinders their growth potential. She averred that SMEs are not real businesses, but rather informal activities that lack innovation, scalability and sustainability. She went on to suggest that SMEs should be replaced by startups instead, which she defined as “businesses that are designed to grow fast.”

What is your analysis of her assertions? I’ll provide mine.

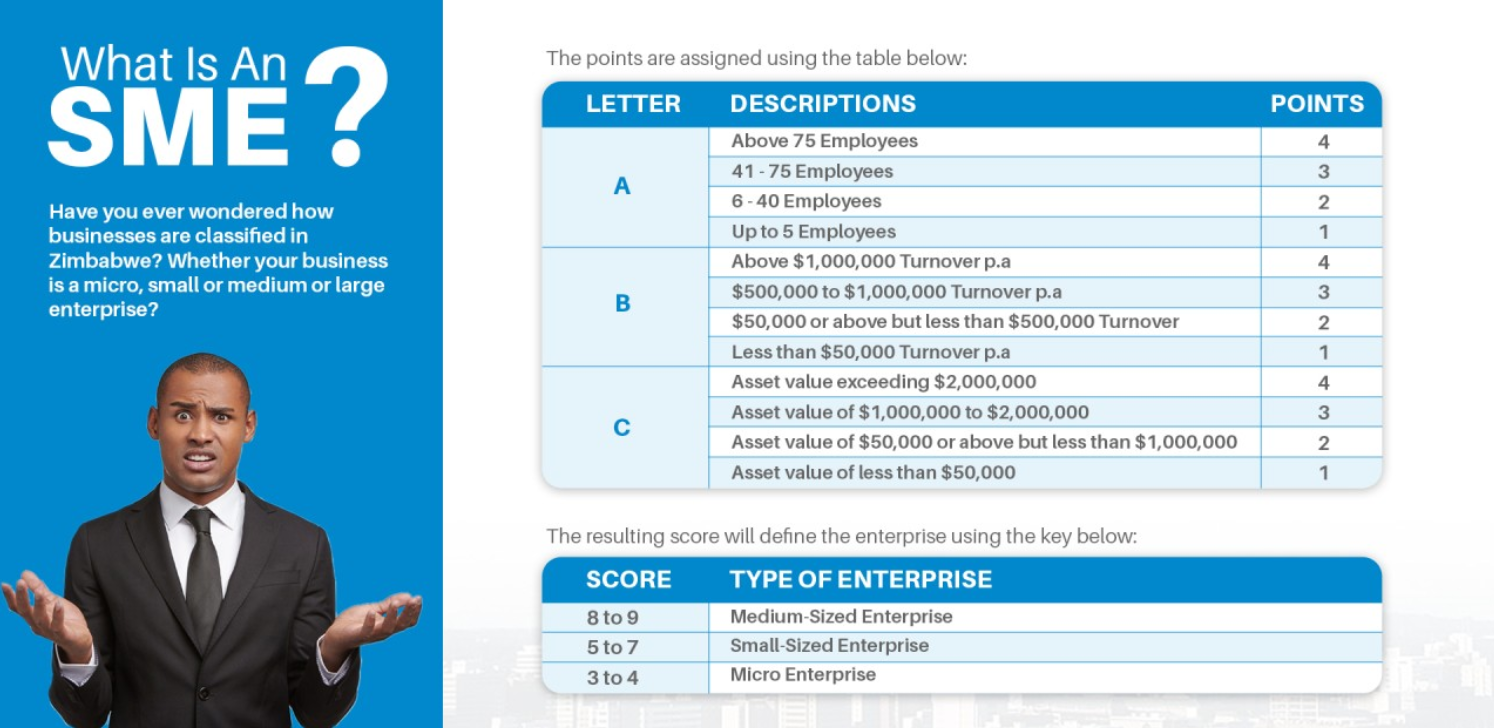

What are SME classifications in Zimbabwe?

Mutema’s views, are more steeped in emotion around the abuse of SMEs in Zimbabwe and the attendant pilferage that may be happening through their funding schemes and the like, but (and this is an important “but”), they are not supported by the evidence and experience of many successful SMEs in Zimbabwe and elsewhere.

In fact, SMEs are the backbone of the Zimbabwean economy, contributing over 60% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and employing over 75% of the workforce in 2023. SMEs thus play a vital role in poverty reduction, income generation, social inclusion and economic diversification.

SMEs most definitely are not a scam, but rather a source of resilience and opportunity for millions of Zimbabweans. What could be is perhaps the support system around them. And we have to state that fact.

Moreover, Mutema’s distinction between SMEs and startups is misleading and inaccurate. Startups are not a separate category of businesses, but rather a stage in the business life cycle.

Startups, which she feels need to “replace” SMEs, are indeed businesses that are designed to grow fast, but they are also, like SMEs, small businesses, and in-fact face high uncertainty, risk and failure rates. Startups therefore are not necessarily more innovative or scalable than SMEs; they are simply more experimental and adaptable.

Importantly, startups can become SMEs if they survive and succeed, and SMEs can become startups if they pivot and innovate, so we can not easily be purist about favouring one and abhorring the other. I could go further and state that those calling SMEs a scam and laud the novelty of startups ignore that "startups are but merely SMEs without a track record", so which is riskier a fresh startup concept or a startup with a business history, which we call an SME?

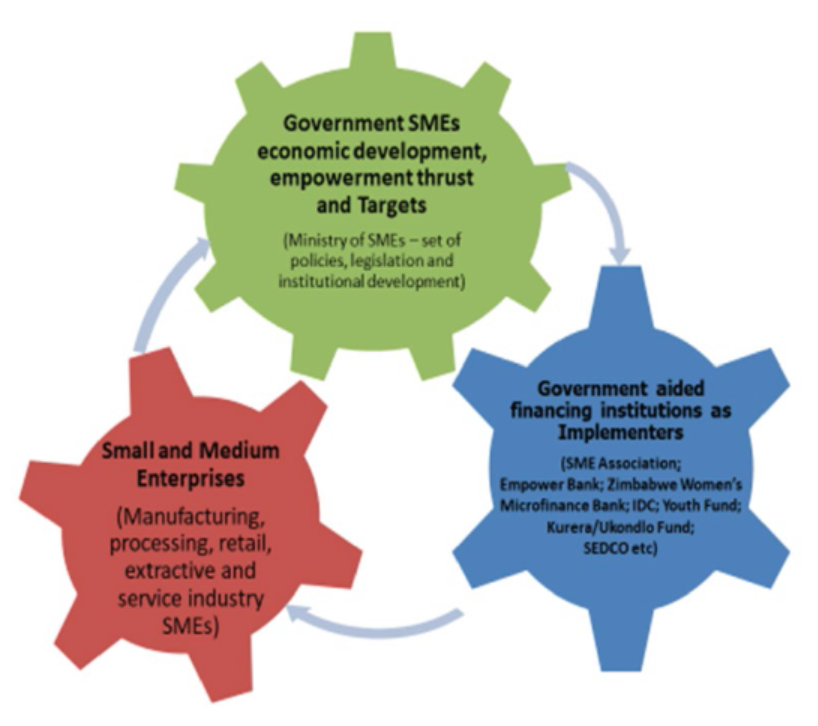

Framework of SMEs government-aided financing relationships. (ZW)

The notion that SMEs are inferior or irrelevant to startups is also contradicted by the experience of other countries that have leveraged the power of small businesses to achieve economic development and social progress. One notable example is Germany, where SMEs are known as the Mittelstand, a term that denotes not only their size, but also their values, culture and performance.

The Mittelstand comprises 99.3% of all German firms, employs 56% of the workforce and generates over half of the net value added in the country. And this is the biggest economy in the European Union which we are talking about.

These German SMEs (Mittelstands) are renowned for innovation, quality, productivity and competitiveness in global markets. When we speak of German precision, surely we are equally giving that accolade to big corporations, like vehicle manufacturers, as much as we are giving it to the country’s SMEs, which not only feed most inputs to these corporates, but are legitimate successful businesses in their own right.

Closer to home, is the example of Rwanda, where SMEs have been instrumental in rebuilding the economy and society after the 1994 genocide. The nation has adopted a comprehensive and inclusive approach to supporting SMEs, providing them with access to finance, skills development, infrastructure, markets and technology.

As a result, SMEs have grown rapidly and diversified into various sectors, such as agriculture, manufacturing, tourism, ICT and renewable energy. They actually account for 98% of all businesses in Rwanda, contribute 41% of GDP and employ 84% of the labour force.

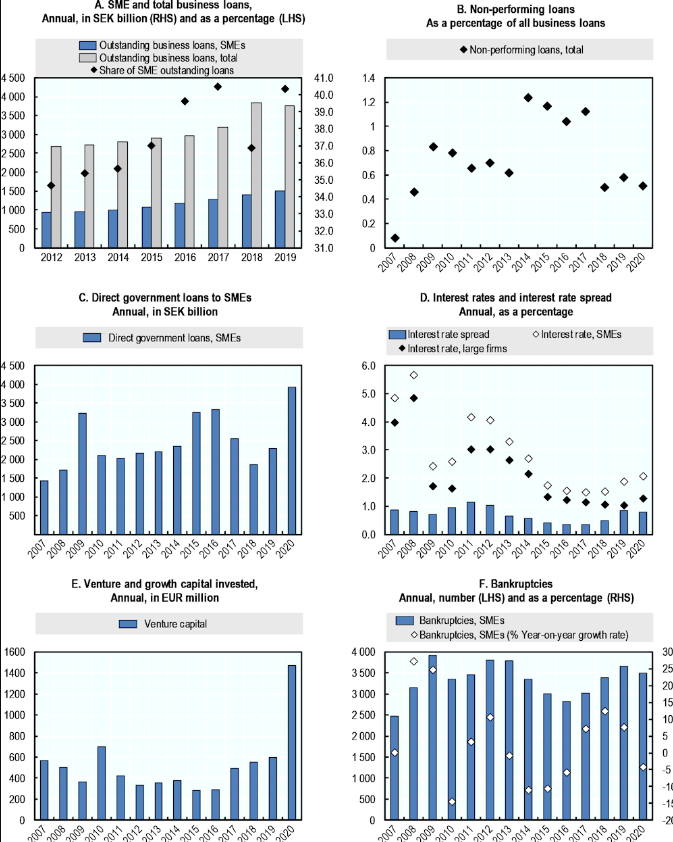

Sweden charts on depth of SME Financing support (2022)

Just check how those figures compare favourably with Germany and you begin to realise that Zimbabwe still has got some way to go in providing an enabling environment for SMEs to thrive. Not to obfuscate their contribution which, by extension, will also limit SME contribution to social cohesion, gender equality and environmental sustainability.

These examples show that SMEs are not a scam, but rather a key driver of economic growth and social development. Zimbabwe can learn from these best practices and adopt policies and strategies that foster a conducive environment for SMEs to thrive.

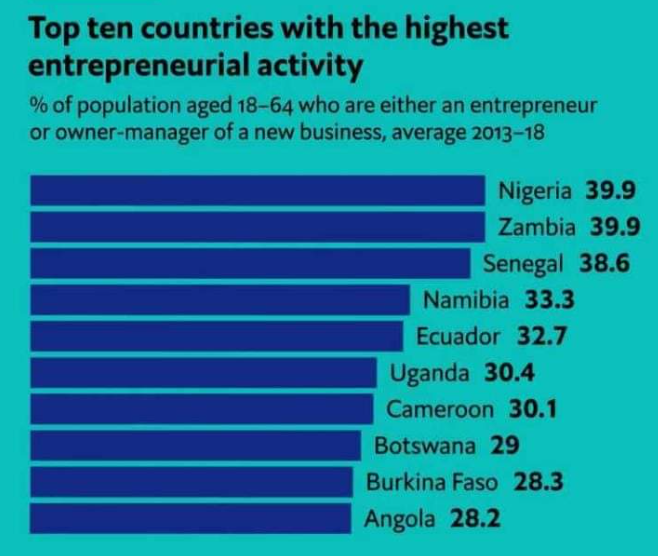

The country can also leverage its own strengths and opportunities, such as its abundant natural resources, its young and entrepreneurial population, its diaspora network and its regional integration . Zimbabwe will definitely need to harness the potential of digital technologies to enhance the innovation, efficiency and competitiveness of its SMEs.

Zimbabwe is the second most informal economy in the world yet it ranks very lowly in the "entrepreneurial activity index."

Why is that?

Having said all this, Mutema’s thread is necessitated by some observations she has made. She is a trained economist after all so we can not be dismissive of her observation, perhaps only remedy proposal. Paradoxically she is an “entrepreneur” (read SME) in her own right.

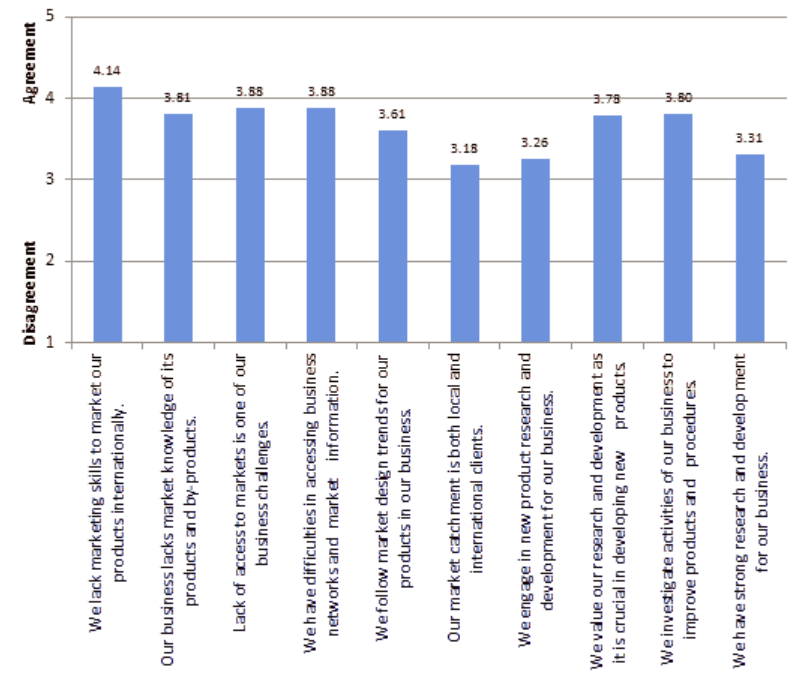

She raised some valid points that deserve attention and action from both the public and private sectors. Mutema rightly criticised some of the challenges and constraints that SMEs face in Zimbabwe, such as lack of access to finance, markets, technology and skills.

We can add high taxes and fees; cumbersome regulations and bureaucracy; corruption and rent-seeking; political interference and instability; macroeconomic volatility and uncertainty; infrastructure gaps and deficiencies; low productivity and quality standards; weak linkages and networks; limited research and development; poor governance and management; low levels of formalisation and compliance; among others.

We definitely understand her implied her frustration with some of the leaders who use SME schemes for illegal self-aggrandisement or political patronage. She accused some of them of abusing public funds meant for supporting SMEs or creating artificial barriers for entry or exit for certain groups or individuals. She argued that these practices undermine the credibility and legitimacy of SME policies and programmes.

In essence her question will need to be if these policies are for the SMEs or are structured such that those with nefarious intentions will take advantage? Im sure there would be many among us who will have similar questions. Trained economists or not.

Challenges Faced by the Informal Small to Medium Enterprises in Zimbabwe.

Indeed some of Zimbabwean policies, on the face of it, meant to benefit SMEs but on application work against SMEs or outright are abused for nefarious benefit.

We could discuss three such policies.

The Indigenisation and Empowerment Policy (IEP), though repealed, aimed to empower Zimbabweans to control the economy of the country by requiring foreign-owned businesses to cede 51% of their shares to indigenous Zimbabweans.

This policy has been criticised for being discriminatory, inconsistent, unclear and politicised. It discouraged foreign investment, reduced competitiveness and created opportunities for corruption and rent-seeking by some of the elites, all which worked against SMEs.

Another such policy is The Zimbabwe Industrial Development Policy (2012-2016), which provided a framework for the development of the industrial sector, including SMEs, by promoting value addition, innovation, competitiveness and linkages.

This policy has been criticised for being unrealistic, outdated, poorly implemented and supported. It has also failed to address the structural and systemic challenges that SMEs face, such as lack of access to finance, markets, technology and skills; limited research and development; poor governance and management; low levels of formalisation and compliance.

Finally we can equally site The National Trade Policy (2012-2016), which sought to enhance the trade performance of the country, including SMEs, by improving market access, trade facilitation, trade promotion and trade negotiation.

This policy has been outright ineffective, irrelevant, uncoordinated and unsupported. It has also failed to address the trade barriers and challenges that SMEs face, such as lack of competitiveness, diversification, innovation and quality; high tariffs (save for SMEs in grocery divisions) and non-tariff barriers; low capacity and awareness; weak institutional and regulatory framework.

Should SMEs in Zimbabwe continue to be housed under the Ministry of Industry and Commerce or, considering their significance, need a stand alone ministry?

(in pic, the Minister of Industry and Commerce 2023, Hon. Sithembiso Nyoni).

We can surely appreciate, if not necessarily sympathise, with Mutema’s observations.

Our point of departure will be on the remedies called for where instead of shifting attention from SMEs we could strengthen and laser focus policies to be precise to SMEs not to industry as a sector.

With enabling policies in place, what of government spearheading for a promulgation of an investment bank where the country has none among its 20 something banks in the land?

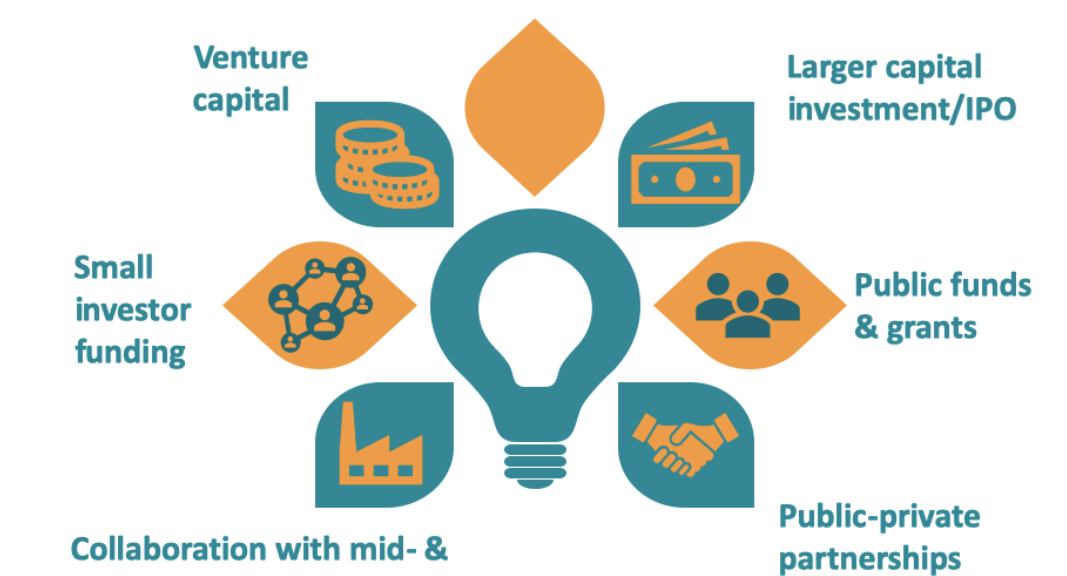

An investment bank would be able to provide specialised services for SMEs, such as equity financing, debt financing, mergers and acquisitions, advisory services, underwriting services, asset management, securities trading and research but all with this target constituency in mind. An investment bank would be able to bridge the gap between SMEs and capital markets and facilitate their access to long-term and affordable finance.

Another issue is the need for an SME stock exchange in Zimbabwe. It is not far fetched to propose that SMEs have their own Exchange category with different listing rules from the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE).

An SME stock exchange would enable SMEs to raise capital from the public by issuing shares or bonds .It would enhance the visibility, credibility and accountability of SMEs and attract more investors and customers. This proposal is not new or unique. Several countries have established or are planning to establish dedicated stock exchanges for SMEs, such as India, China, South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, Egypt, Turkey, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile . These countries have recognised the potential benefits of SME stock exchanges for their economies and societies.

SME funding eco-system

Therefore, Zimbabwe needs to adopt a holistic and pragmatic approach to establishing and developing an SME stock exchange that takes into account the specific needs, characteristics and circumstances of the country. Zimbabwe needs to learn from the best practices and lessons of other countries that have implemented or are implementing SME stock exchanges. Zimbabwe also needs to engage and consult with various stakeholders such as SMEs, investors, regulators, intermediaries, service providers and experts to design and implement a suitable framework and model for an SME stock exchange that is inclusive, efficient, transparent and credible.

An SME stock exchange is not a panacea or a silver bullet for the challenges that SMEs face in Zimbabwe. It is not a substitute or a replacement for other forms of finance or support for SMEs in Zimbabwe. Neither is it a competition or a threat for other segments or participants of the capital market in Zimbabwe. The exchange is a complement or an addition to the existing financial system and ecosystem in Zimbabwe and is an opportunity or a potential for enhancing the performance and potential of SMEs in Zimbabwe.

The long and short of it is that SMEs are not a scam; they are a solution. Zimbabwe needs to eliminate the undesirables alluded to in this article and enhance the support system of this constituency which is to embrace the power of small businesses and support them to grow bigger and better.

SMEs need that. Zimbabwe needs that.