Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, has received a third loan from the World Bank in less than six months, raising concerns about its debt sustainability and economic management. The latest loan, worth $700 million, was approved on September 26, 2023, and is intended to improve governance and service delivery at the state and local levels.

This follows two previous loans of $750 million and $500 million, approved on June 9 and June 22, respectively, to boost the country’s power sector and women’s empowerment. The total amount of World Bank loans to Nigeria since President Tinubu took office in May 2023 now stands at $1.9 billion.

As analysts we are wont to question the rationale and feasibility of authorities borrowing more money from the World Bank, which already holds about 40% of Nigeria’s external debt, amid a worsening economic situation. Nigeria already faces high inflation, which reached 25.8% in August 2023, the highest since September 2005, reflecting the impact of the removal of fuel subsidies, the devaluation of the official exchange rate and security issues in food-producing regions.

The total amount of World Bank loans to Nigeria since President Tinubu took office in May 2023 now stands at $1.9 billion.

The exchange rate has slid tremendously and as at the time of writing this article in September 2023, that rate stood at US$1 to 780 Naira, a depreciation of about 40% since the beginning of the year.

This has increased the cost of servicing Nigeria’s external debt, which stood at $38 billion as of June 2023, equivalent to about 13.6% of GDP. The debt service-to-revenue ratio, which measures the proportion of government revenue used to pay interest and principal on debt, rose to 73.5% in 2023, exceeding a government limit of 50%. This means that Nigeria has less fiscal space to invest in critical sectors such as health, education and infrastructure.

Security issues in food-producing regions also continue to dog this African giant lending credence to the question if the opening of World Bank tap for President Tinubu will quench Nigeria's many thirsts?

The paradox of the new government running on a promise to reduce debt and tighten money supply then going to do the exact opposite in just five months of ascendency to office has piqued our interest. President Tinubu, who campaigned on a platform of fiscal discipline and monetary stability, has been accused of reneging on his pledges and succumbing to political pressures. There is also the issue of opaqueness that accompanies about the accountability of the World Bank loans, which are often tied to conditionalities that may not align with Nigeria’s development priorities.

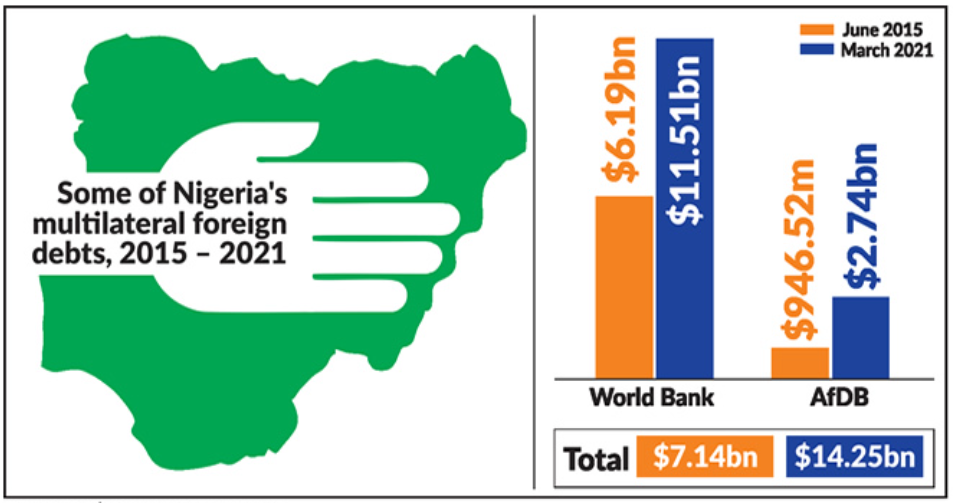

Nigeria's loans from World Bank, AfDB rose to $14.35bn under Buhari.

The World Bank, for its part, has defended its lending to Nigeria, saying that it is aimed at supporting the country’s long-term growth and poverty reduction goals. The bank has also stressed that it is working closely with the Nigerian authorities to ensure that the loans are used effectively and efficiently. The bank has said that "it is providing technical assistance and policy advice to help Nigeria improve its macroeconomic management, public financial management and debt sustainability."

However, some experts have warned that Nigeria, already in a debt trap, may completely fail to extricate itself in the short and medium term from this vicious cycle, where it borrows more money to pay off existing debts. The country has to be addressing underlying structural problems that hinder its economic performance more than just throwing borrowed money at national predicaments.

They have urged the government to adopt a more prudent and sustainable approach to borrowing, by diversifying its sources of finance, increasing its domestic revenue mobilisation and enhancing its debt management capacity. Also indispensable is the need for more fiscal and monetary policy coordination and coherence, as well as greater transparency and accountability in the use of public funds, to enable efficient needs-based deployment of existing revenue.

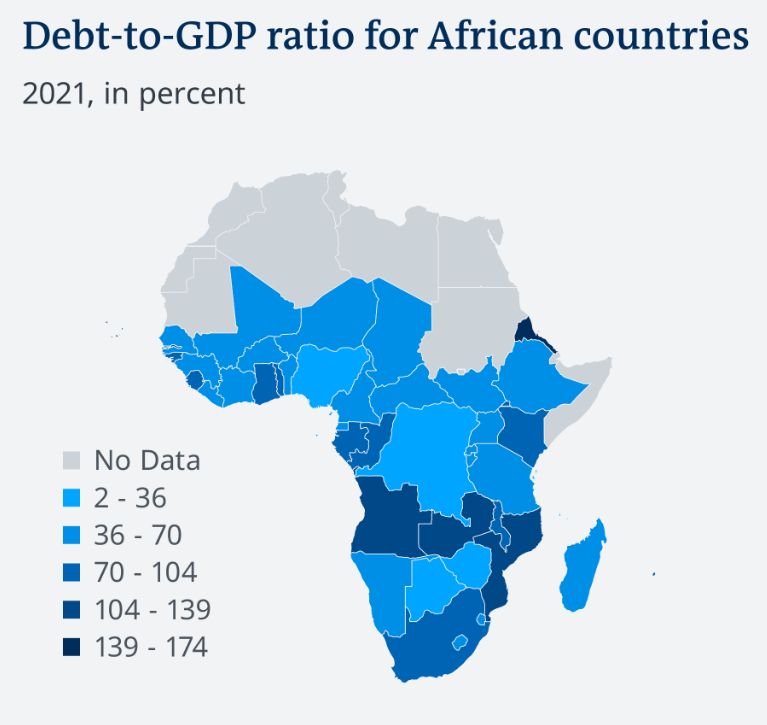

Nigeria’s debt situation is not unique in Africa, however, as many more countries have seen their debt burdens rise sharply in recent years as well. According to the World Bank, sub-Saharan Africa’s average debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 45% in 2021 to 58% in 2022. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has classified six African countries as being in debt distress and 14 others as being at high risk of debt distress.

Africa's debt burden threatens to slow economic recovery

(Source - International Monetary Funds' World Economic Outlook Database)

To this end, the IMF and the World Bank have launched several initiatives to provide debt relief and restructuring to eligible countries, such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI.

Be that as it may, these initiatives have been criticised as being insufficient and inadequate to address the scale and complexity of Africa’s debt challenges. Some civil society groups have called for a more comprehensive and holistic approach that would involve a cancellation or write-off of some of Africa’s debts, especially those owed to multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF. They have also demanded more democratic and participatory processes for negotiating and managing debt issues, as well as more accountability and oversight mechanisms to ensure that borrowed funds are used for public good. Which is the is the main qualm in Nigeria around the quickening rate of borrowing funds and the deployment of the same.

Nigeria’s debt crisis is not inevitable or irreversible. With political will and collective action, the country can overcome its current difficulties and chart a path towards sustainable development.

This will require a radical rethink of its relationship with external creditors such as the World Bank, as well as a fundamental reform of its economic and governance systems. Nigeria, and indeed all other African nations, cannot afford to mortgage its future for short-term gains. It must act now to free itself from the shackles of debt and reclaim its sovereignty and dignity.