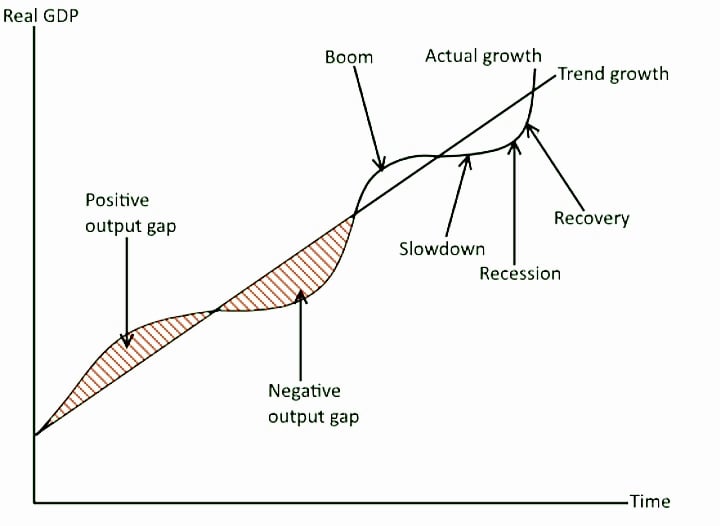

Negative Output Gaps Occurances during GDP growth.

Zimbabwe has been experiencing a modest economic recovery since 2021, after a decade of stagnation and hyperinflation. The country's nominal gross domestic product (GDP), which measures the total monetary or market value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country's borders in a specific time period - in this case a calendar year - has increased from US$24.6 billion in 2021 to US$34.2 billion, according to the World Bank.

However, the country's Minister of Finance and Economic Development, Hon. Prof. Mthuli Ncube, has been quoted saying the country's GDP is currently at US$40 billion. Regardless which of the two values is closest to the mark, this still represents a growth rate above 15% in each year, reaching 19.5% in 2022, the highest in the region.

Be that as it may, these impressive numbers mask a potential problem:

The quality and distribution of economic output, as well as the environmental and social costs and benefits of economic activity, are not reflected in the GDP figures.

GDP emphasizes material output without considering overall well-being and ignores business-to-business activity, which can overstate the importance of consumption relative to production in the economy. Therefore, alongside GDP, it is important to consider measures such as the Human Development Index (HDI) and the distribution of GDP among the residents of a country to gain a more holistic view of economic development and well-being.

Moreover, nominal GDP does not account for the impact of inflation on economic data. Zimbabwe has been suffering from high inflation for long now. In the recent episode, the inflation rate peaked at 837.5% in July 2020, before gradually declining to 55% in December 2023. So GDP growth, though desirable, is not needed for it's own sake, but in so far as it uplifts the general population's standard of living, which NDS1 and 2 espouse, but which GDP growth alone, without being married to inflation and distribution, does not show.

At least to cater for evaluating actual economic impact on everyday lives of people in an economy, by adjust for the effect of inflation, economists use real GDP. This measures the value of economic output in constant prices, using a base year as a reference point. Real GDP reveals the actual growth or contraction of economic output, taking into account the impact of inflation on economic data as well as country's economic advantages.

Should we put our calculated real GDP for Zimbabwe instead of this nominal GDP being pronounced left right and centre? In any case the NDS speaks of "Real GDP" as a metric of measuring its success so quoting nominal GDP is actually counter to the outcome pronouncements for both NDSs pronounced by the government.

Without publishing our calculated number, Zimbabwe's real GDP growth rate has been much lower than its nominal GDP growth rate, due to the high inflation rate. In fact, in 2021, the country experienced a negative real GDP growth rate of -8.5%, according to those calculations, indicating a contraction of economic output in real terms!

In 2022 and 2023, the real GDP growth rate improved to 6.5% and 4.5%, respectively, but still below the regional average of 7.2% and 6.1%, according to the African Development Bank itself.

The discrepancy between nominal and real GDP growth rates illustrates the paradox of Zimbabwe's economic growth:

more GDP is great for the economy and those with equity stake in the productive sectors of the economy, but not necessarily so for the generality of the populace who will content with a testing economic environment without the means.

GDP growth, though desirable, can surely not be the whole objective. Besides economic fundamentals diluting "quality" of growth there is also the question of what that growth consists of in the first place. GDP can be driven by activities that are infact not valuable, sustainable, or equitable.

For instance, if we dig 10 holes at a value of US$1,000 for each hole, then fill up those same 10 holes at a cost of US$5,000 each, by definition we have a GDP of US$150,000. But, to start with, is that activity "valuable"? Thus so much can be captured as "economic activity" therefore contribute to GDP growth, without necessarily meaningful entailing meaningful development.

Likewise, increasing the number of holes to be dug then filled in, by GDP measure, will show "growth". But in what? Such an activity is wasteful, unproductive, and harmful in the long run.

Therefore, a more nuanced and comprehensive approach to measuring economic activity, development, and well-being is needed. One that takes into account not only the quantity but also the quality and distribution of economic output, as well as the environmental and social costs and benefits of economic activity. Such an approach would allow for a more accurate and meaningful assessment of the impact and effectiveness of Zimbabwe's development strategies, and provide a better basis for policy-making and planning for the future of the country.

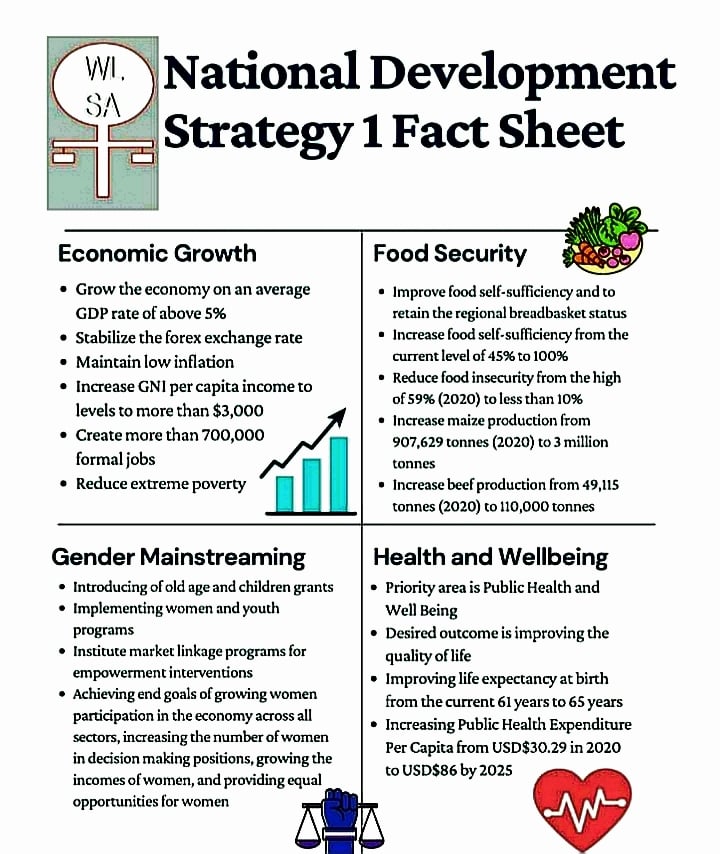

Zimbabwe's NDS1 factsheet

Zimbabwe's development strategy, the National Development Strategy 1 (NDS1), which covers the period from 2021 to 2023, aimed to achieve real GDP growth, strengthen macroeconomic stability, attract both foreign and domestic investors, promote new enterprise development, and align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The strategy has achieved some of its objectives, such as reducing the fiscal deficit, stabilising macro, and increasing agricultural and mining output. However, it has also faced some challenges, such as global headwinds, structural bottlenecks, price and exchange rate instability, and fiscal pressures.

Moreover, the NDS1 has not adequately addressed the issues of poverty, inequality, unemployment, and governance, which are critical for the well-being of the people and the sustainability of the economy. More so because it looks it holistic figures, which may paint a picture of "collective" well being, yet the "collective" is but only a mathematical averaging.

The NDS2, which is expected to cover the period from 2024 to 2026, has to be strengthened to build on the achievements and challenges of the NDS1, and possibly continue the focus on economic growth, job creation, infrastructure development, and SDG alignment, but with emphasis on how much of this cascades to, and percolates at, the bottom of the pyramid.

This will see the NDS2 acknowledging where the NDS1 fell short, and incorporating a more holistic and inclusive approach to measuring and achieving economic development and well-being. The NDS2 will also need to address the macroeconomic challenges, such as public debt arrears, inflation, and exchange rate volatility, which pose a threat to the stability and growth of the economy.

The World Bank projects that Zimbabwe's economic growth will decline to 3.5% in 2024, as agricultural output is expected to suffer from depressed global growth and the predicted erratic and below-average rainfall caused by the El Niño weather pattern (although the last two weeks have seen more hopeful precipitation which may stem that World Bank projection).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), on the other hand has been sending mixed reviews, some showing a gloomy outlook for Zimbabwe in 2024, due to a combination of factors such as debt overhang, contested elections, lack of political reforms, anticipated liquidity crunch, costly food imports, and low receipts from commodity exports, while other reports show a resilient and growing economy mitigating risks and managing under challenging conditions.

The NDS2 implementation may be strengthened by:

- Implementing sound macroeconomic policies that ensure fiscal discipline, monetary stability (with the advent of the newly minted reserve bank governor), and debt sustainability which is consistent with the country's economic objectives and realities.

- Enhancing the business environment and investment climate by improving the legal and regulatory framework, strengthening the rule of law and property rights, reducing bureaucracy, and promoting transparency and accountability.

- Diversifying the economic base and increasing productivity and competitiveness by fostering innovation and entrepreneurship, supporting value addition and beneficiation, developing human capital and skills, and (continuing) investing in infrastructure and technology.

- Promoting inclusive and sustainable development by reducing poverty and inequality, creating decent jobs and livelihoods, improving access to quality health and education services, protecting the environment and natural resources, and advancing gender equality and social justice.

- (continuing) engaging in constructive dialogue and cooperation with the international community, especially the multilateral institutions, the creditors, and the development partners, to mobilise financial and technical support, resolve the debt arrears, and restore confidence and trust.

Zimbabwe has the potential to achieve its vision of becoming an upper-middle-income country by 2030, as envisaged by the NDS1 and NDS2. This though will require a concerted and coordinated effort by all stakeholders, including the private sector, the civil society, and the international community, to address the challenges and opportunities that Zimbabwe faces.

More importantly, it will require a paradigm shift in the way the country measures and pursues economic development and well-being. One that goes beyond GDP, and embraces a more holistic and comprehensive approach which also takes into account actual distribution/use of national economic gains.