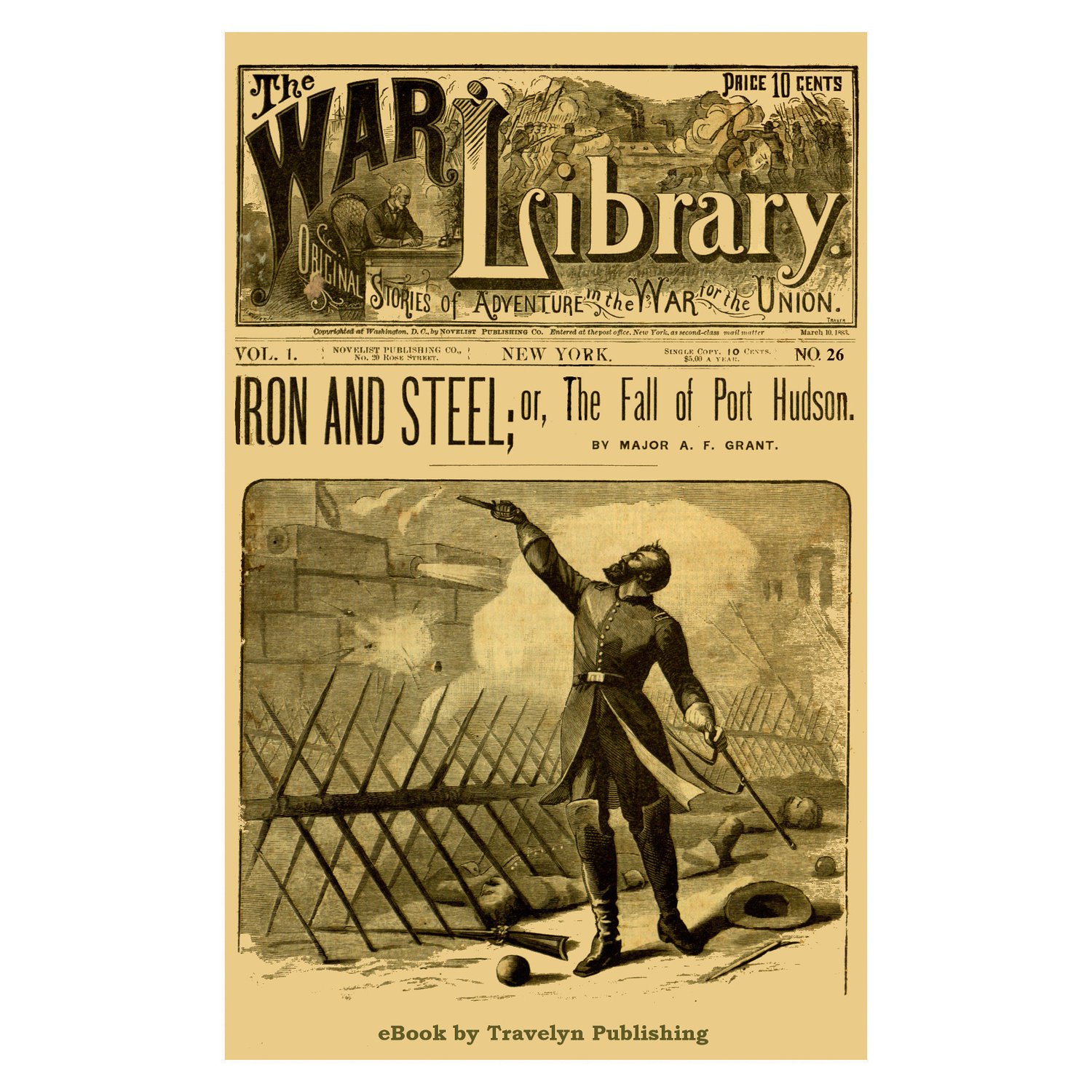

Iron and Steel; or, The Fall of Port Hudson

“The War Library,” originally published in the 1880s by Novelist Publishing Co. in New York, is a series of dime novels about the American Civil War—or, as the war was called at the time (at least by the sympathizers of the North), “the War for the Union.” Featuring characters, stories, and plotlines set in the midst of, or vicinity of, actual Civil War battles, and written by authors who seemed to possess first-hand knowledge of those battles, the War Library provides the reader with a unique chance to experience, from a personal perspective, the conditions, passions, and philosophical issues of one of the most fascinating periods in history. Civil War buffs, of which there are many, can do no better.

Iron and Steel; or, The Fall of Port Hudson, number 26 of the series and originally published March 10, 1883, is a story of romance, obsession, and espionage that takes place in the midst of the bloody siege of Port Hudson (May 22–July 9, 1863) on the Mississippi, a confrontation that cost thousands of Union lives and was finally settled by hunger, when Rebel forces ultimately surrendered because of lack of supplies.

The listed author, “Major A. F. Grant,” was one of the pen names used by Thomas Chalmers Harbaugh (1849–1924), generally credited as “Col. Thomas C. Harbaugh” on his works of fiction though there is no evidence in his scant biography of ever having been an actual colonel. Harbaugh was a prolific producer of pulp fiction, writing at a pace of one thriller per week at the peak of his career. According to Wikipedia, Mr. Harbaugh “died penniless in the Miami County Poor House, Ohio;” suggesting that dime novelists were compensated poorly for their work.

Preparing old books (or, as in this case, weekly magazines) for digital publication is a labor of love at Travelyn Publishing. We hold our digital versions of public domain books up against any others with no fear of the comparison. Our conversion work is meticulous, utilizing a process designed to eliminate errors, maximize reader enjoyment, and recreate as much as possible the atmosphere of the original book even as we are adding the navigation and formatting necessary for a good digital book. While remaining faithful to a writer’s original words, and the spellings and usages of his era, we are not above correcting obvious mistakes. If the printer became distracted after placing an ‘a’ at the end of a line and then placed another ‘a’ at the beginning of the next line (they used to do this stuff by hand you know!), what sort of mindless robots would allow that careless error to be preserved for all eternity in the digital version, too? Not us. That’s why we have the audacity to claim that our re-publications are often better than the originals.