In “Learnability Isn't Enough: How to Design Apps That Are Easy to Use in the Long Run, Not Just the First Run,” Hans van de Bruggen challenges conventional wisdom in user interface design, presenting a compelling case for prioritizing long-term usability alongside initial learnability. This insightful work offers a fresh perspective on interface design, particularly relevant for professionals creating tools used frequently or for extended periods.

Van de Bruggen's central thesis revolves around the distinction between two types of usability effort: learning effort and ergonomic effort. While the former has long been a focus in UI design, the author argues convincingly that the latter has been largely overlooked, leading to interfaces that may be initially intuitive but become frustrating for experienced users over time. This premise is not merely theoretical; van de Bruggen supports it with engaging real-world examples and personal anecdotes from his extensive experience in product design.

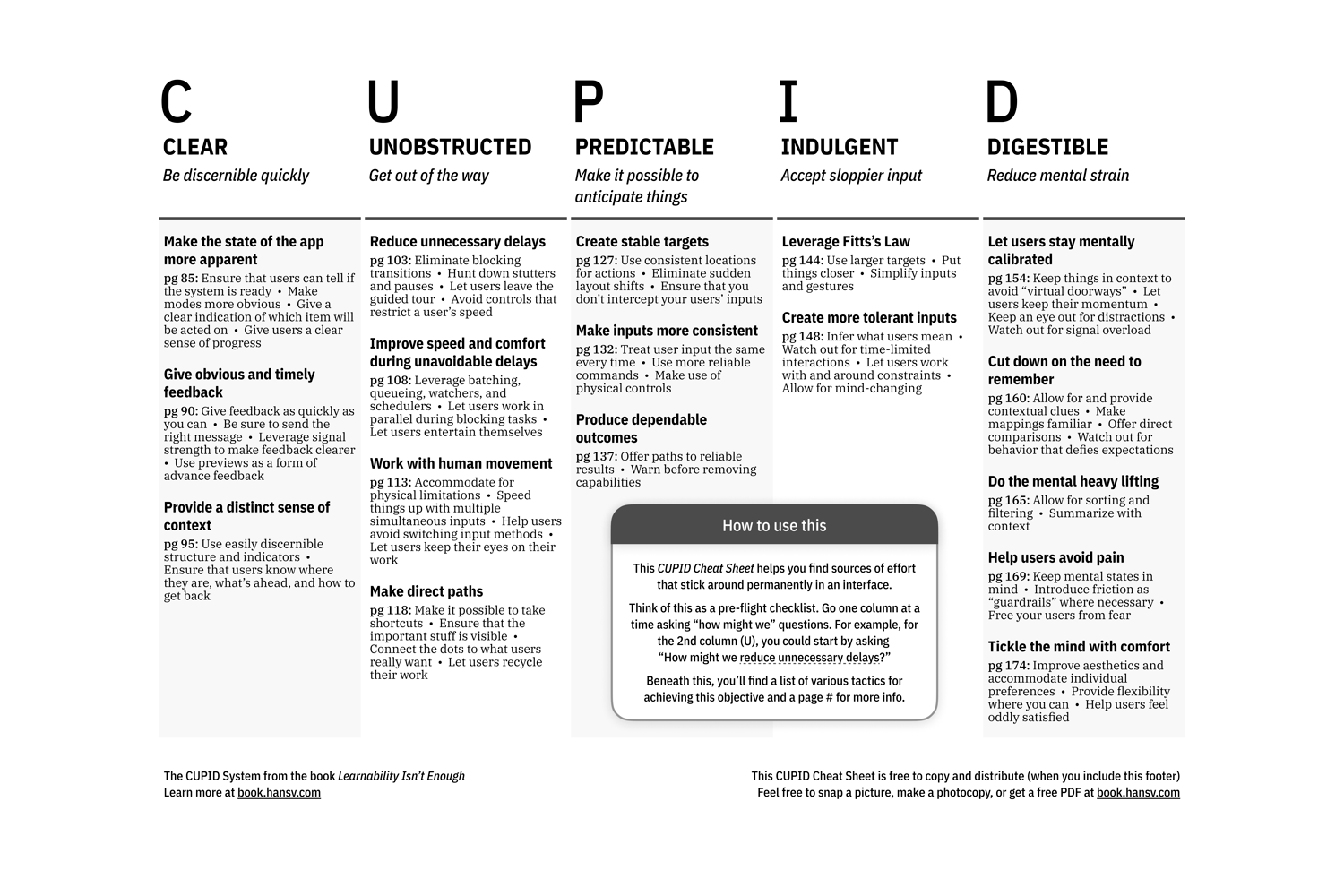

The book's structure is well-crafted, guiding readers through the concept of UI Ergonomics before introducing practical tools and frameworks. The CUPID System (Clear, Unobstructed, Predictable, Indulgent, Digestible) serves as the backbone of van de Bruggen's approach, offering designers a systematic method to identify and address ergonomic issues in their interfaces. This framework is particularly valuable as it provides actionable insights that can be applied throughout the design process.

One of the book's strengths lies in its practical tools, such as the Usability Matrix and the Product Pyramid. These visual aids not only help solidify the author's concepts but also offer tangible ways for designers to evaluate and improve their work. The Usability Matrix, in particular, stands out as an innovative tool for comparing interfaces based on both learning and ergonomic effort, potentially revolutionizing how designers prioritize improvements.

Van de Bruggen's writing style is accessible and engaging, striking a balance between theoretical concepts and practical application. He deftly weaves in stories from his own career, including mistakes and learning experiences, which lend credibility to his arguments and make the content more relatable for readers. This approach helps to demystify complex design principles and makes the book valuable for both seasoned professionals and those new to the field.

While the book's focus on professional tools and frequently used interfaces is a strength, it may limit its applicability for designers working on more casual or infrequently used applications. However, the principles presented can still offer valuable insights for a wide range of design scenarios.

One of the most thought-provoking aspects of the book is its challenge to the common excuse that “users hate change.” Van de Bruggen argues that users are actually receptive to changes that improve their long-term experience, even if these changes require some initial learning effort. This perspective could significantly influence how designers approach interface updates and redesigns.

“Learnability Isn't Enough” makes a significant contribution to the field of user interface design by highlighting the often-overlooked importance of ergonomic effort. It provides designers with a new lens through which to view their work, potentially leading to interfaces that not only attract new users but also retain and satisfy them over the long term.

The book's ideas are particularly timely in an era where digital tools play an increasingly central role in both professional and personal life. As users spend more time interacting with interfaces, the cumulative impact of ergonomic effort becomes ever more crucial. Van de Bruggen's work serves as a wake-up call to the design community, urging a reevaluation of priorities and approaches.

Overall, “Learnability Isn't Enough” is a must-read for UX designers, product managers, and anyone involved in creating digital interfaces. It offers a fresh perspective on usability, backed by practical tools and frameworks. While it may challenge some long-held beliefs in the field, it does so with well-reasoned arguments and evidence. This book has the potential to spark important conversations within the design community and lead to more thoughtful, user-centric interface designs. It's not just a guide to better design; it's an invitation to rethink our approach to usability in the digital age.