1 – What was your initial reason for getting involved in publishing – please try to think of this in the spirit of what you were thinking and doing at the time.

I realized that my writing would not be acceptable to commercial or conventional publishers. This situation continues even today with my fourth novel, Unlevel Crossings, currently doing the rejection rounds. It has been the same for my poetry, although my first two books of poetry were published by Lancaster Publishing and Martian Way Press respectively. Most of the other writers I have published were in a similar situation and my decision to be a publisher was influenced a lot by watching writers who I thought were talented not being able to get their work in print because they weren’t in vogue.

In 1984 I had a job with the Auckland City Council writing and preparing for publication two books on Auckland cemeteries. I used the knowledge gained at this time to set up the Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop. My original concept revolved around the idea of setting up a factory in one of Auckland’s industrial areas like Penrose. From this site many artists, writers etc. would spend their days and nights working on projects, much in the way a conventional factory operates, except the final product would be an art work or a book rather than a car or a refrigerator – this somewhat fanciful dada/surrealist notion was the genesis of ESAW. In fact, at the time David Eggleton and I were carrying out a limited version of this concept. Four days a week, we were making various artifacts, and the remaining three days we would go into downtown Auckland to sell them on the streets – this was in the days when such things were illegal, an added incentive for us!

2 – Who or what was your main influence behind your decision to publish? These may include literary or non-literary influences.

My main influence to be involved in literature came through two rather different avenues. As a young person my main inspiration came from the ’60s pop music, in particular the lyrics of the Beatles and the two books of prose and poetry by John Lennon. As I wrote in the poem ‘Flip Side of the Ballad of John and Yoko’, written when Lennon was shot: ‘Your songs and books helped me discover / In myself, what all the education in the world / Could not; that I could write and illustrate my own story.’ Later I came under the influence of James K. Baxter, Marcel Duchamp, Oscar Wilde and James Joyce all of whom have left their mark on the way I do things as an artist, writer and publisher.

I have always been driven by a sense of destiny, an intensity of passion and belief, and the need to make a positive contribution to ‘life’, the fact that we all fall short of the glory of God I see as being not my fault but my humanity. The fact that the muse has lead me to some illicit and dangerous places is just part of the fate of an artist.

3 – In your choice of authors was the main consideration for inclusion philosophical, literary or pragmatic?

A mixture of all three, sometimes all on the same project.

4 – ‘…and if there is still a number of commissioned works which seem to have been dreamed up by a sabotaging office-boy on an LSD trip, there are now each year a growing quantity of books which worthily add to our literature.’ – Professor J.C. Reid from an article introducing New Zealand Books in Print, written in 1968. I interpret Reid’s assessment as an indication of the rift between the acceptable ‘worthy’ literature as endorsed by academia, and the new wave of sabotaging office boys and girls who at that time commissioned publishers to put out their works, or simply published things themselves, and in many cases the work of their friends. Comment on this quote in relation to the ‘Vanity Press’ vs ‘Real Publishing’ debate.

I feel that this 1968 quote is significant because it draws the demarcation line between what is seen as acceptable and what is not in literary terms, and by implication makes academia the final arbiter over what is ‘worthy’ and what is not. As a publisher it has always been my policy that the author knows best. Thus, the poets and writers whom I have published have always been free to present to the world their work of art the way they want it to appear without editorial interference from me (although I have always made myself available if people want my opinion or advice). The fact that some of the drug-addled office boys of the ’60s have become the conservative academics and latter-day critics and protectors of public taste in literary matters, is ironic indeed.

As far as the argument over vanity publishing goes, I am of the mind that all publication can be considered a ‘vanity’ in the sense that someone is arrogant enough to feel that they have something worthwhile to say, outside their immediate circle, and that it is being set down for posterity, is indeed a vanity. So the argument is one of whose vanity is more credible or readable or better- presented, rather than a shallow, indeed vane, assertion about ‘standards’! Or, to put it another way, in the matter of literature – ‘Vanity, Vanity; all is Vanity!’

5 – Initially, was your focus outwardly cosmopolitan or inwardly New Zealand looking, and how has this emphasis changed over the years?

My emphasis has been on the cosmopolitan nature of New Zealand/Aotearoa, and because most of my publishing has been carried out in cities, my emphasis has been urban-focused.

6 – What were your methods of printing and distribution as a publisher? Did you receive any financial or other assistance from either public organisations, or private sponsorship?

Most of ESAW publications were printed by an Auckland commercial printer, The Print Centre, up until about 1990. In the same period distribution was done by Brick Row Publishers. Since then both publishing and distribution has been erratic and various. For example, The Irish Annals of New Zealand was printed by the University of Otago Printery and primarily distributed through my Dunedin bookshop, O’Books.

Thus far I have received only one publishing grant, from the NZ Literary Fund to assist with the publication of Wrapper. (I have received two small grants to assist with my writing as well.) Auckland University Students Association funded The City Assails. Whitireia Polytech helped with both Waiting for a Train of Thought and Nine Seasons.

7 – How much of your publishing was commissioned and paid for (either fully or partially) by the author? Was your operation helped by the voluntary work of friends and family?

About half and half of my publishing was the way my system operated. Finance has always been a difficulty. At one stage I was grinding concrete for twelve hours a night and running a bookshop during the day to pay for the publishing I was doing (during the ’80s in Auckland). I have always treated equally the work offered to me for publication, whether paid for by the author or by myself, although some things would obviously not have been done if the author had not been able to fund it – however that would have been a decision based on financial rather than literary grounds.

I have always been blessed with many people around me who have been willing to put time and energy into my many projects over the years. Whether it is my extended whanau, the Seacliff Mafia (whose tentacles are long and varied), or the authors themselves, people have embraced the concept of shared work and my debt and gratefulness is with them.

8 – What has been the cost to you personally in terms of time, money and resources, of being involved in publishing in New Zealand? You may consider this in relation to more difficult areas such as relationships with friends, family etc. also.

Much of the last twenty years of my life has been dedicated to these things. The cost to me has been the sacrifice of more conventional aspects of goals and achievements that may be the ambition of other men in our society. However, I knew very early on that dedicating my life to being an artist, in whatever form that took, was going to mean a certain amount of difficulty and isolation. I accept that this is why I haven’t got a wife and a family in the ordinary sense, or a good career – I accept that my lack of business acumen has lead all my ventures into financial ruin and me into huge personal debt – or high-paying job, why I can’t buy a house and to a large extent have to remain vulnerable to the obvious insecurities inherent in such a lifestyle. However, I have many close friends and supporters who believe in my work as much as I do myself, and who are prepared to help me despite my short-comings. Ka pai to mahi tatau, no reira.

9 – Where do you place yourself and your achievements as a publisher (and as a writer if applicable) in the history of the modern-day New Zealand literary scene? Do you feel that your contribution has been adequately acknowledged.

I feel that as a publisher my achievements lie somewhere in the middle of the field. Apart from obvious exceptions, the number of publications I have produced is comparable to similar operations. I have been attentive to aesthetic aspects of book production as well as literary ones, and feel the books I have produced look good. I feel that the 1992 anthology, Wrapper, is yet to be recognised for its true value, and the novel Passion (1990) – New Zealand’s first locally published homosexual novel, which unfortunately got bogged-down in issues that had more to with gay politics than actual literary merits.

As for my writing career, I feel that even though it’s taking a long time my achievements are beginning to gain recognition, and my recent inclusion in both the Oxford History of New Zealand Literature (2nd ed.) and the Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature attests to this fact. As to the future I will continue to pursue my artistic career in whatever form that takes.

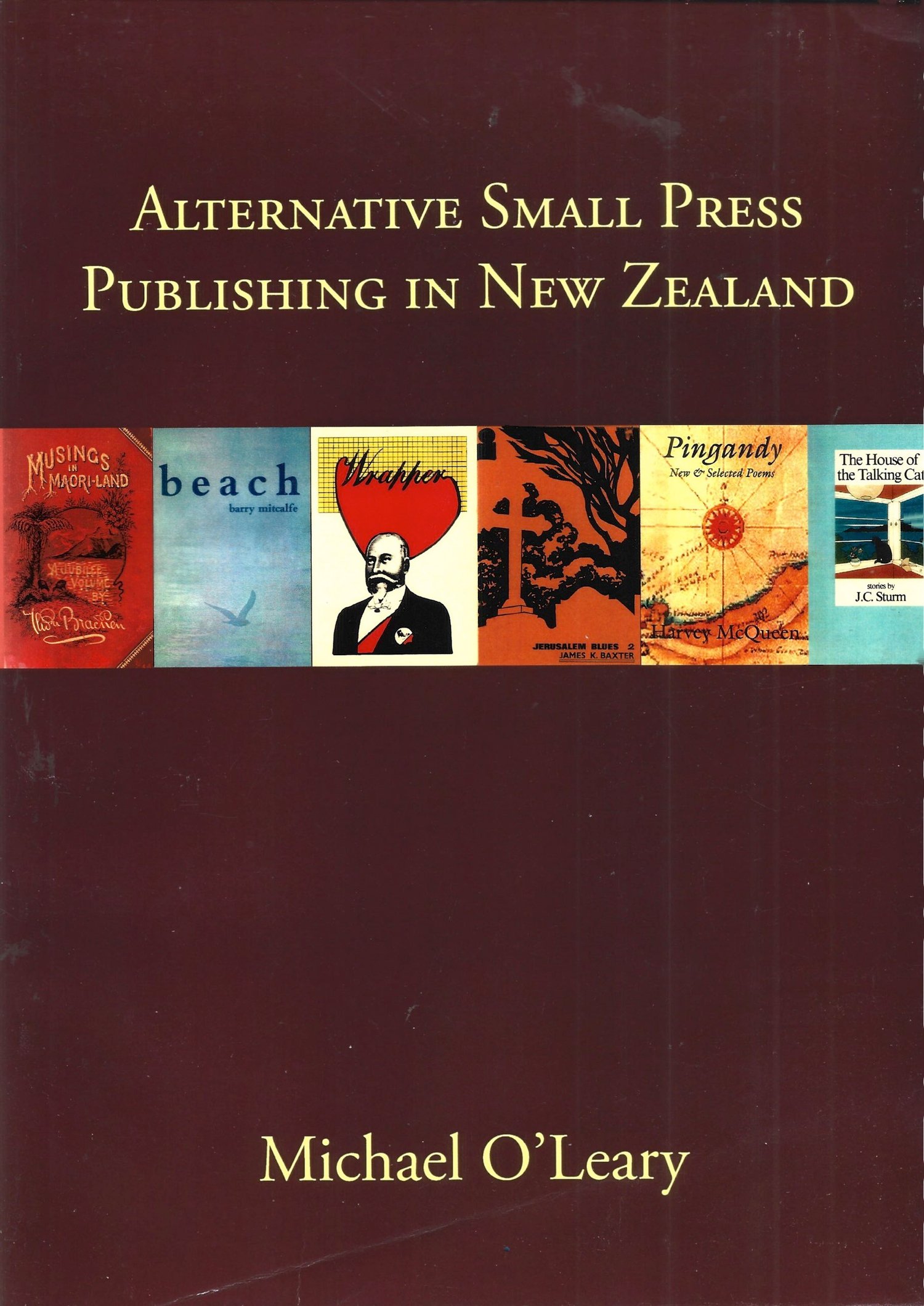

(Editor’s Note: This self-interview from 1999 is a response to a questionnaire that Michael O’Leary sent to small press publishers that year. Michael published the responses he received from small presses in his book, Alternative Small Press Publishing in New Zealand (1969-1999). Michael decided, however, not to include his self-interview in the book. It was published in The Earl is in…: 25 Years of the Earl of Seacliff for the first time.

Since Michael wrote this response, ESAW has published over 100 titles.)