Rebel writer with a cause by Richard Langston

When Michael O’Leary – aka the Earl of Seacliff – moved from Auckland to Seacliff near Dunedin to work on his third novel, he brought with him 12 boxes of books and a stuffed hawk.

Books he regards as a vital companion, and the hawk was perched on one of his big shoulders to provoke a reaction from his fellow train passengers. He enjoys recounting the response he got from the American tourists … ‘would you look at that guy with the bird Martha!’

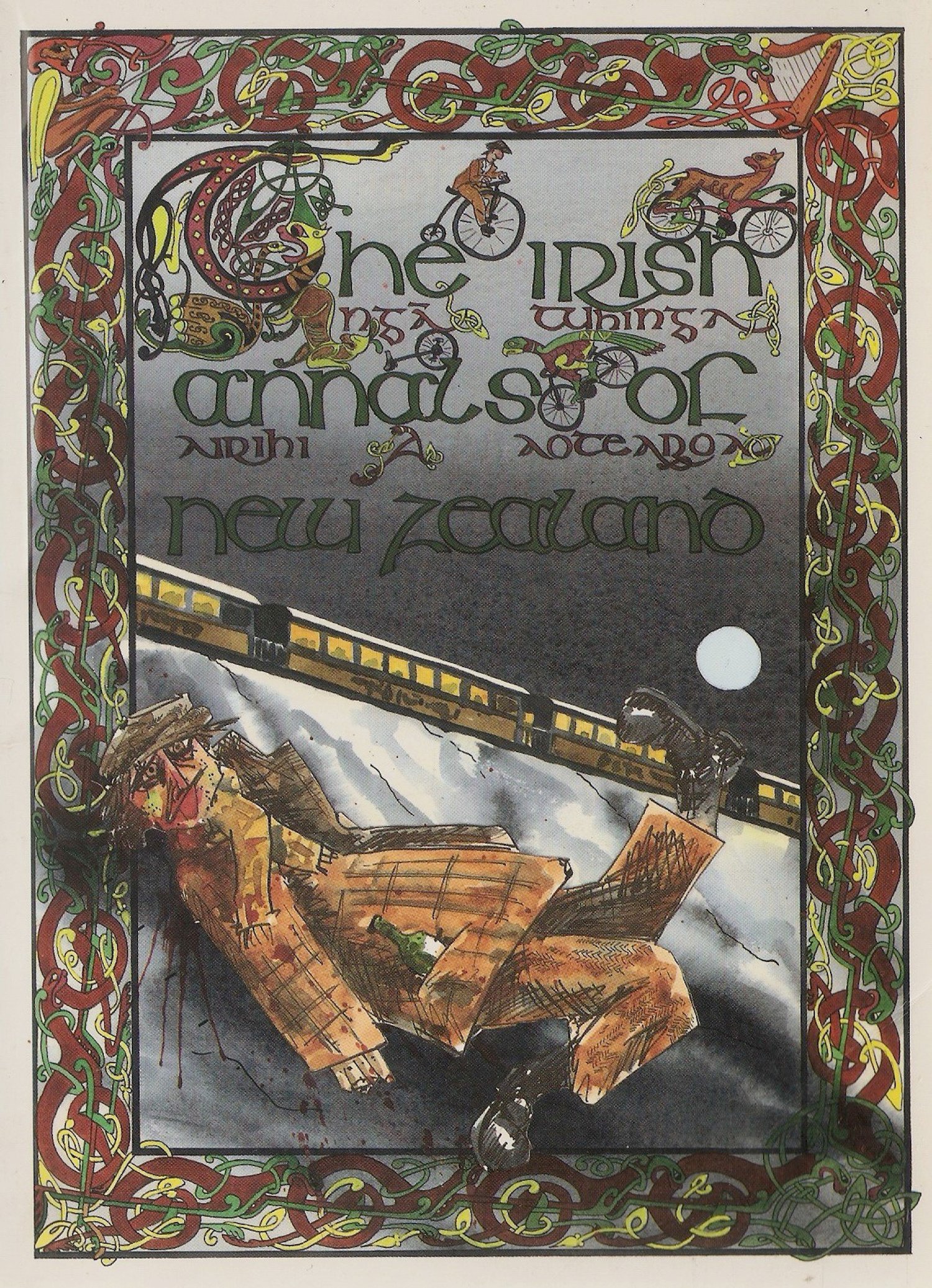

The bird now hangs in a perpetual pose of attack from the ceiling of the Seacliff cottage where he’s been working on the novel for several months. The book, called The Irish Annals of New Zealand, is a sort of late-coming 1990 project from the other side of the fence, mixing the stories of what O’Leary regards as two of the rebel cultures in this country – the Irish and the Māori.

You couldn’t call it history, he says; it’s more of a melding of the personal, the real and unreal, though it does draw on actual happenings, such as the fact that a nun who was the sister of James Joyce lived on the West Coast for 40 years. Stylistically, he laughs through his black beard, it’s Milligan meets Beckett.

‘It begins in 1990 in the North Island when a drunk falls off a train in the middle of the night. He breaks every bone in his body and he’s left lying there in the snow. His Irish and Mäori ancestors come up to meet him … they’re all on bikes. The book travels back through the previous 150 years and it’s all about him trying to understand his life.’

O’Leary himself is a confluence of Irish and Māori blood, and he says it’s given him an outsider’s perspective on this country – ‘the Irish came here to escape the English and the potato famine, not like the Anglo-Saxons who came to conquer. The Irish were dispossessed of their land just like the Māori.’

His bloodline, coupled with a Catholic upbringing – ‘being brought up a Catholic is like being brought up in Disneyland, except everything is painted black’ led him to write. ‘I haven’t come from a background of being surrounded by books – we hardly had any in our house – but I’ve always had this thing with words. I used to make up pop songs as a kid and I’d always be telling stories to other kids on the way home from school.

‘But I didn’t start reading books till my mid-twenties when I went to night school to do School Cert and University Entrance. By reading books I could better understand what’s happened to me and where I’ve come, that’s the main contribution writers make – you come across something you recognise and you learn more about yourself.’ O’Leary, however, doesn’t see writing as being a po-faced, serious, cerebral activity, regarding it as no more important than the labouring jobs he’s had. New Zealand literature, he maintains, has been hi-jacked by the academics, and lacks humour.

He’s kicked against that and writes satire: his second novel, Out of It, focuses on the ruminations of Patrick Malone, and is set at a cricket match between New Zealand and the ‘Out of It’ 11, captained by Te Rauparaha, and featuring dead sixties rock heroes, Nazis, and writers, including a seminal influence, James K. Baxter.

‘On one labouring job I left a copy of Out of It in the smoko shed. I worked with some pretty hard characters and they recognised the title and had a laugh at that and one or two of them read it. They really liked it which means more to me than what some university-type might say.’

He expects his new book to be out later this year. Like his others, it’ll be self-published through his company, Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, which has promoted an alternative roster of writers, including poet David Eggleton; the country’s first gay novel, Passion, and a book on the Rainbow Warrior affair by Colin Amery. O’Leary’s labouring stints, including a nightshift job grinding concrete on Auckland’s Queen Street, have kept the venture solvent. He’s returned to Seacliff to free himself of the hassle of being a business director, and write the book which has been brewing in his head for three or four years.

He loves the small coastal settlement so much he named himself the Earl of it, partly in jest and partly in defiance of the English having ‘exterminated’ the Irish Earls back in the 18th century. Having grown up among the state houses of Ōrākei in Auckland, he values Seacliff for its solitude, its rolling greenness, its open summer skies contrasting with brooding coastal mists, and its infamous mental hospital. ‘A lot of people won’t come out here because of that,’ he says, pointing across the road to the old brick building of the hospital, ‘but to me it just adds to the whole atmosphere.

‘From the first moment I ever saw Seacliff from the window of the train I felt an empathy with it. My rationale now is that because it’s so physically beautiful yet has a tormented past it brings out something in me which gives an expression of my view of life. The fact it’s half beautiful and half terrifying.’

(From Dominion Sunday Times, 10 March 1991)