This is a follow up article to one about Nvidia’s valuation, compared to Saudi Aramco’s.

This time, yet again, it’s another comparison, albeit with deeper analysis.

In 1999, Lucent Technologies made what appeared a clever discovery. Telecom demand was slowing, but Wall Street didn’t like that story. To keep numbers growing, Lucent began to finance its own customers.

Billions of US$ were lent to newly formed carriers, who used the very funds to buy Lucent’s fibre and switches. The accounting looked brilliant and revenue and the stock price both surged.

But when those small carriers defaulted, because there were few actual end users of all that fiber, the magic unraveled. Lucent took a seven‑billion‑dollar write‑off, Cisco collapsed almost ninety percent in value, and the Nasdaq fell seventy‑eight percent from its peak. The real culprit was “structural leverage” masquerading as demand.

Since the first article on Nvidia, a thorough assessment has uncovered a similar, if not improved, “structural leverage,” hence this follow up piece.

So, two decades later, Nvidia appears to have perfected the same script, except this time the company believes it has closed the fatal loop Lucent made. The old flaw was debt. Debt defaults. Equity does not. Nvidia’s version of Lucent’s game works through ownership, not loans.

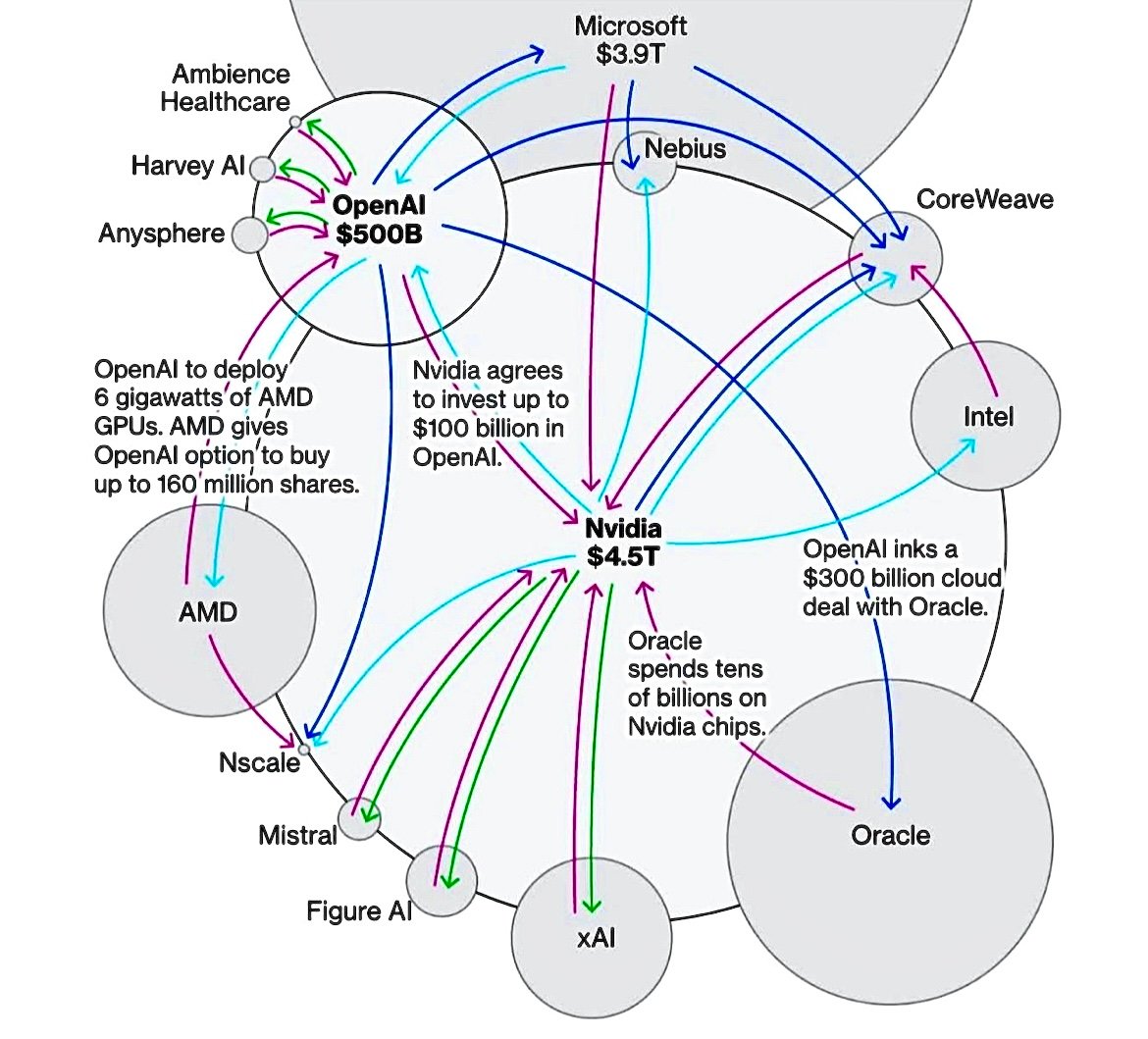

Instead of lending money to its customers, Nvidia takes equity stakes in them. CoreWeave, for example, a cloud startup filled mainly with Nvidia chips, is financed by Nvidia itself. OpenAI, which depends heavily on Nvidia hardware, received commitments exceeding a hundred billion dollars from the same source.

If these partners succeed, Nvidia reports revenue; when they struggle, Nvidia still holds equity positions in businesses that already own Nvidia’s products. Either path leads back to Nvidia’s balance sheet.

Thus, the deeper innovation from Nvidia’s valuation is not only on the technology side, but also on financial technicalities, particularly within contractual structuring. Nvidia has an agreement to purchase any unused compute capacity from CoreWeave through to 2032!

That means if AI demand collapses tomorrow, Nvidia has effectively promised to buy back its own chips, only through a different accounting route. It sounds almost elegant. The company becomes its own customer of last resort. Demand looks permanent because Nvidia has written itself into the transaction on both sides.

From a cash‑flow statement perspective, money leaves the firm as “investment,” travels through subsidiaries or partners, and comes back as “revenue.” If this looks circular that is because it is. Yet in the short run, everything checks out. Auditors see real inventory moving and verifiable payments. Analysts, in turn, upgrade growth projections. The financial loop has no obvious starting point or ending.

And guess what that does to the stock price both in the short and medium term?

Furthermore, this structure is now mutating. OpenAI, itself backed by investors like Thrive Capital, has purchased a stake in Thrive Holdings, a special‑purpose entity linked back to Thrive’s portfolio companies. The result is an ecosystem where suppliers, investors, and customers overlap so tightly that independence disappears.

A case just like Volkswagen AG, as a parent company, completely owning Porsche, but somehow Porsche being the majority shareholder of Volkswagen AG (an incestuous relationship analysis for another day).

OpenAI invests in firms that deploy OpenAI models. Those deployments justify further Nvidia hardware purchases. Thrive’s capital gains derive from valuation uplifts built on those same GPU purchases. The economic signal resembles perpetual motion more than market feedback. Engineers among us will tell you the folly of perpetual motion machines. But this is finance. Different kind of laws apply in this dimension.

No one can claim it is fraud either. Everything follows disclosure rules. There is no misrepresentation of accounts per se, yet the market mechanism becomes distorted. Capital markets function because feedback exists (people make decisions, buyers decide if a product justifies its price, inefficient players fail etc).

When the supplier owns the buyer, however, and the investor funds them both, price ceases to signal real demand and supply equilibrium point. The result is what behavioural finance calls “reflexivity,” but on steroids in this case as valuation itself is driving adoption then adoption is feeding the same valuation some more. Yet another closed loop.

Back to the Lucent example, it’s flaw was visible because its debts eventually defaulted. Nvidia’s system hides risk inside equity and forward purchase obligations. When it owns both the revenue source and the risk exposure, external visibility falls to near zero. The loop sustains itself until someone asks what proportion of revenue originates from organic, independent buyers.

In Nvidia’s case, close to forty percent of reported revenue comes from only three hyperscalers alongside Meta. These, in turn, are tied to OpenAI’s extraordinarily optimistic spending projection, roughly 1.4 trillion dollars in future outlay, against actual revenues estimated around fifteen billion this year.

Analysing such a structure, what becomes apparent is the conflation of top‑line growth with economic value creation. In valuation theory, enterprise value ultimately converges to discounted future free cash flow. Future free cash flow itself relies on sustainable, external end demand. When that demand is internally financed, like in this Nvidia case, the terminal value used in discounted cash flow analysis becomes unanchored.

Put simply, Nvidia’s “growth” depends substantially on internal funding and less on external clients at the moment, so its future cash flows, and thus its true value, can’t be reliably estimated using standard valuation methods. So the inputs feed upon themselves.

In quantitative terms, one could say beta approaches zero because the firm has hedged demand risk through ownership, yet alpha inflates artificially, as there is no exogenous benchmark to measure performance against.

Investor type trends also complicate this further. About a quarter of all equity market turnover now comes from retail investors. That is you and me with device in hand and hype and speculation driving our decision. That number is up from less than ten percent two decades ago. As one can surmise, retail investors often trade based on price momentum rather than cash‑flow analysis. This inflates distortion between intrinsic value and market capitalisation. Then, as reflexivity deepens, the feedback loop between retail enthusiasm, index inclusion, and corporate multiples strengthens.

This makes Nvidia’s valuation pattern appear self‑confirming. Prices rise simply because prices have risen!

In the previous article comparing Nvidia’s market capitalisation of 4.2 trillion then, with Saudi Aramco’s 1.6 trillion, highlights that such a multiple only makes rational sense if Nvidia functions as essential infrastructure for a new industrial epoch. Aramco extracts, refines, and delivers physical energy; Nvidia, by contrast, transforms electrical power into computational energy, which may or may not yet substitute human labor at scale.

The distinction matters because the former’s value chain links to final consumption - cars, fuel, heat - whereas Nvidia’s chain still loops largely inside capital expenditure cycles among similar entities.

Read the first article here:

https://payhip.com/admiremaparadzadube/blog/news/so-nvidia-is-valued-at-4-2t-and-saudi-aramco-1-6t

The AI economy might very well evolve into what economists term a “transformative general‑purpose technology.” If so, the circular financing model would merely represent an early‑stage bootstrapping of inevitable adoption. But this assumption rests on hypothesis, not cash flow.

If AI productivity gains stall, the valuation framework collapses because cost of capital rises while real revenues lag. Nvidia’s commitments to repurchase capacity turn into obligations rather than optionalities. Liquidity ratios could shrink rapidly. In that case, earnings quality deteriorates as the proportion of non‑cash or internal transactions increases relative to free operating cash flow.

This modelling of potential downside scenarios borrows from stress‑testing methodology used in credit risk analysis. If we use a Monte Carlo simulation adjusting for earnings elasticity to end‑demand shifts, a thirty‑percent decline in AI infrastructure spending reduces Nvidia’s projected free cash flow by more than half due to fixed cost absorption and contractual purchase liabilities.

The asset‑beta correlation then inverts, meaning as equity values fall, volatility increases, compounding the drawdown. This could trigger forced deleveraging among funds heavily indexed on Nvidia’s weight, not unlike what happened to subprime Collaterised Debt Obligation tranches in 2008, albeit through equity exposure rather than debt default.

The more benign scenario assumes AI indeed replaces segments of human labour, in which case Nvidia captures the expanding capital supply of the new machine economy. Then what looks like circular financing today transforms into vertical integration, and the cash flow becomes closer to utility‑scale infrastructure yield. At which stage current and future growth is confirmed by “external client” demand, therefore becomes unadulterated.

The transition between these two possible scenarios depends on how fast end‑user adoption converts into hard revenue. At the moment, that data is thin.

From a valuation standpoint, the market seems to be pricing Nvidia as though success is nearly certain. The forward price‑to‑free‑cash‑flow multiple exceeds a level justified even by the most optimistic cost of equity assumptions.

Assuming a marginal cost of capital around eight percent and long‑term Free Cash Flow (cash from operations less capital expenditure) growth at twelve percent, the implied market value already exceeds the output of conventional Gordon growth formulas.

This inconsistency suggests markets are using narrative extrapolations rather than analytical valuations.

Technical analysts sometimes argue that all this fundamental gibberish doesn’t matter in late‑cycle phases because sentiment trumps fundamentals. They’re half right, but also half wrong because it matters eventually.

When cyclical liquidity dries or CapEx cuts ripple through hyperscalers, elasticity of demand reveals its true slope, and it is rarely infinite. The illusion of perpetual demand ends not in a crash, but in what financial historians call a “grinding unwind,” that is, valuation compressing quarter after quarter.

Nvidia’s innovation, therefore, lies in semiconductors, and more also in how it has re‑engineered the flow of capital to mimic relentless demand. The risk, of course, is that you can simulate revenue, but you cannot simulate utility. When the economy’s output fails to match the balance sheet’s optimism, the whole construction wobbles.

For now one will assume that they have done their “engineering” precise that by the time simulated revenue forces ebb, real external client demand will have peaked that it would not matter anyway.

The technical conclusion drawn from financial analysis is pragmatic. Equity can disappear as swiftly as debt when it represents recycled cash rather than new value creation. Structural circularity may delay reckoning, not eliminate it.

Whether this ends as Lucent 2.0 or transforms into the biggest industrial leap since electricity, it all depends on AI’s conversion efficiency into real productivity. The uptake of it from you and I.

Until then, Nvidia’s narrative remains both masterpiece and mirage, a balance sheet perpetually in motion but perhaps standing still all at the same.

So once again the question remains, is data the new oil? Does this also transfer to each’s pricing, where with oil we needed to see the barrels since it’s physical, and with data we can accept the abstract because it’s not?

Food for thought.